|

Searching for the Earliest Talking Machine Made in Canada

by Bill Pratt

Montreal Star, February 23, 1900, p. 1

|

|

On February 23, 1900, Emile Berliner posted an announcement on the front page of the Montreal Star:

The store No. 2315 St. Catherine street has been leased for the exclusive sale of the Berliner Gramophones and will be occupied by the undersigned shortly. These machines and the records are now being made in Canada.

Three years later, on March 20, 1903, the Owen Sound Sun published a report on the company that gave an alternate date for the first manufacture of the Berliner Gram-o-phone in Canada:

In May, 1900, the manufacture was begun in Canada of that most wonderful machine which reproduces the human voice so faithfully that it is popularly called the 'talking machine', or gram-o-phone. So great has been the favor that this entertaining invention has enjoyed, that in two years the output has so increased, that two factories are required to supply the demand. The Gram-o-phones are manufactured at 367 to 371 Aqueduct Street, and the records at 2315 to 2319 St. Catherine Street, Montreal. Up to the time of the manufacture of these machines in Montreal, the Canadian market was supplied from abroad, and the machine which is now sold at $15, was, on account of duty and other charges, sold at $35. Every province in Canada and Newfoundland is now supplied from the Montreal factories.

"The only Talking Machine Made in Canada"

Montreal Star, December 20, 1902, p.19

|

|

Exactly when the Gram-o-phone was first manufactured in its entirety in Canada is unclear. However, after Berliner moved his operations from the United States to Canada in 1899, he began assembling the Gram-o-phone using a cabinet manufactured at his Montreal factory and accessories imported from Eldridge Johnson, Camden, New Jersey. Well into the 1910s, this was still the common practice for many talking machine brands that were promoted and advertised as "Made in Canada" - the cabinets were manufactured locally and the final product was assembled locally using a few imported parts. With this definition for a Canadian-made product in mind, the Berliner Gram-o-phone was first "made in Canada" some time in 1899.

For the next five years, through May, 1905, E. Berliner used the expression "The only Talking Machine Made in Canada" prominently in many of the company's advertisements in Canadian newspapers. Phonograph advertising was overwhelmingly dominated by Berliner, Edison and Columbia - the "Big Three" - and, to a lesser extent, Zonophone, and while both Edison and Columbia did set up factories in Canada at a later date, during this period all of their manufacturing was done in the U.S. So, for several years at the turn of the 20th century, Berliner had a monopoly on the Canadian market with the only talking machine made in Canada.

But, was the Berliner Gram-o-phone the "earliest" talking machine made in Canada?

Initial newspaper announcement of

the Canadian Talking Machine

London Advertiser, December 16, 1898, p. 5

|

|

No doubt there were inventive Canadians who tried their hand at duplicating the inventions of Edison and Berliner. One report looked promising. The Ottawa Daily Citizen of April 23, 1896, gave a brief description on page 7 of a performance at Grant's Hall by Harry Lindley, a well-loved, itinerant, Canadian theatre comedian-actor-manager. The performance included a translation of a three-act French comedy followed by

a mechanical invention of Lindley's, 'The Talking Machine', giving the Remedial Bill, followed by a farce 'Ici on Parle Francais'.

The Province (Vancouver), May 11, 1898, p. 4, reported a testimonial in the final performance of the Harry Lindley Company at the city music hall:

The principal one of these attractions will be an exhibition of one of Mr. Lindley's own inventions, a mechanical talking machine, which speaks in five different languages. The instrument is not a phonograph, nor does it resemble any of Edison's inventions in any particular.

Searching further back into the history of Harry Lindley and his talking machine, we found a report of his Ottawa debut in Othello on March 31, 1874 where:

the treat of the evening so far as mirth and amusement were concerned was Professor Lindley's Talking Machine, which was composed of boards and nails, and it gave imitations of the human voice, laughter, the French, Italian, German and Greek languages. (Pepper's Ghost is Tearing its Hair: Ottawa Theatre in the 1870s by Mary M. Brown)

In a footnote in the same article:

One week earlier, a Professor and Mrs Fabre had equal success with their talking machine at Gowan's.

The Lindley and Fabre "talking machines" pre-dated even Edison's invention and were not early phonographs but rather devices that gave the illusion of sound and speech. One highly sophisticated example of this type of speaking automaton was the "Euphonia" perfected by Joseph Faber in the 1840s. Arthur Zimmerman gave a good account of these "machines that talk" in his article "Not Mr. Edison's Talking Machine" published in Antique Phonograph News in 2013 - https://capsnews.org/apn2013-3.htm.

Another Canadian inventor at the time was Rev. Daniel B. Marsh. Born in 1859 in Grey County, Ontario, and educated at Knox College and Toronto University, he was pastor of the First Presbyterian Church at Blackheath, near Hamilton, Ontario. A report in the Ottawa Journal, April 10, 1897, p. 10, described Marsh's invention of the stethophone, a medical appliance similar to the stethoscope, of utmost value to physicians. The report ended with this interesting comment:

In the quiet life of his village home Mr. Marsh found time to pursue his favorite studies in the theories of light, heat and sound, and before his stethophone was invented he constructed a 'talking machine', which is capable of repeating sounds with many times the force of the machines used at entertainments.

How fascinating it would be to know more about this singular device which may have been a variation on the Edison cylinder phonograph but which could apparently play sounds at significantly greater volume. However, since it did not see commercial distribution, it hardly qualifies as an example of early talking machine production in Canada.

2nd newspaper report of

the Canadian Talking Machine

Windsor Star, December 28, 1898, p. 2

|

|

There is, however, a good candidate for this distinction.

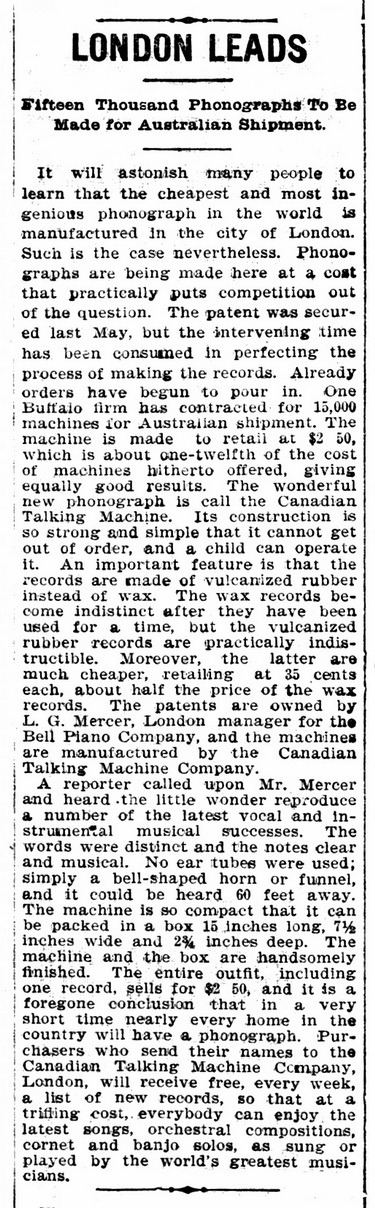

An intriguing article, headlined "London Leads", was published on December 16, 1898 in the London Advertiser, followed by a shorter article, headlined "Canadian Phonograph", which conveyed substantially the same facts, two weeks later on December 28, 1898 in the Windsor Star. The December 16 article announced that

It will astonish many people to learn that the cheapest and most ingenious phonograph in the world is manufactured in the city of London (Ontario).

The patent for the machine, which the article reported was secured seven months earlier in May 1898, was owned by L.G. Mercer, manager of the London Warerooms of the Bell Organ & Piano Co. Limited, whose factory was located in Guelph, Ontario, and the machine was manufactured by the Canadian Talking Machine Company (CTMCo), London, Ontario.

The article stated that the machine was made to retail at $2.50, including one record, with additional records available at 35 cents, and orders had begun pouring in, especially from a firm in Buffalo, New York, that had contracted for 15,000 units for shipment to Australia. Purchasers who sent their names to the CTMCo, London, would receive a list of new records, free, every week. Of special note:

A reporter called upon Mr. Mercer and heard the little wonder reproduce a number of the latest vocal and instrumental musical successes.

This told us that production of the Canadian Talking Machine was already underway in December 1898.

The first advertisement that we found for the Canadian Talking Machine was in the weekly newspaper, The Glencoe Transcript, dated February 9, 1899. The display ad was repeated in successive issues through May 4, a total of 10 identical advertisements. Glencoe was a small village located 60 km southwest of London.

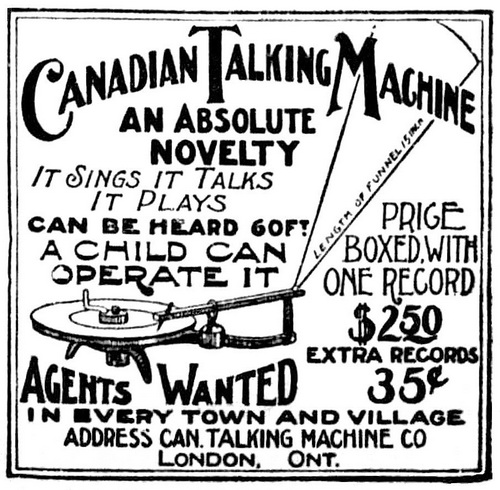

Canadian Talking Machine. An absolute novelty. It sings it talks it plays. Can be heard 60 ft. A child can operate it. Price boxed, with one record $2.50, extra records 35 cents. Agents wanted in every town and village. Address Can. Talking Machine Co., London, Ont.

The Glencoe Transcript, February 9, 1899, p. 5

|

|

The ad included a sketch of the machine which showed a metal tripod stand with a round central shaft and a horizontal extension. A vertical crank was attached to the spindle of a turntable which sat on the stand. Resting on a vertical column at the end of the extension was a horizontal wood arm with an attached 15" horn projecting out and up at an angle from the end. A sliding weight hung down from the centre of the arm and a needle, which was inserted at a slant through the other end of the arm, rested on the turntable. A curious design, unlike any talking machine seen in the phonograph literature.

The CTMCo did not coin the expression "It sings it talks it plays". Edison used it as early as 1895 to advertise the Phonograph. Columbia used it in 1898 to advertise the Graphophone and Berliner followed suit in 1902 to advertise the Gram-o-phone. Nor was the phrase "A child can operate it" original. Berliner ads in 1896 stated "So easy a child can operate it". Similarly the Echophone, a cylinder machine introduced in the same year, advertised "any child can operate it", as did a dozen other companies in 1896 selling products as diverse as folding beds, self lighting gas burners, self sealing oil cans, a musical trumpet and a child's base-ball game. It was a common expression used to convey the simplicity and ease of operation of a product. Deceptively simple in construction, the Canadian Talking Machine, however, had some novel features, ahead of its time. Especially striking was the tonearm assembly, consisting of a solid wood weighted bar and a long steel needle, which foreshadowed a design later adopted by the Vitaphone Company.

The next mention of the CTMCo in the Canadian press, after the initial display ad on February 9, was a notice in the London Advertiser on February 18, 1899: Mr. Childs, a recent graduate of Coo's Shorthand and Business Academy, 76 Dundas Street, London, had been placed with the CTMCo. We can only speculate that the initial display ad attracted interest and the company was recruiting employees in anticipation of increased sales.

A placement with the CTMCo

London Advertiser, February 18, 1899, p. 6

|

|

The Canadian Talking Machine Company's initial strategy was to blanket the small towns and villages in close proximity to London with its display ad. Beginning on February 23, 1899, the ad appeared in the Aylmer Express and was repeated weekly through September 28, a total of 23 ads. On March 24, they advertised in the Wingham Times and, beginning on April 20, in the Dutton Advance, an ad they repeated through the summer, ending on August 3. In May the company went further afield and published the display ad in the Owen Sound Times on May 4, June 8, June 22, July 6, August 3 and August 10. These are all of the newspapers that we have had access to; there may have been others. Aylmer was a town with about 2,100 inhabitants in 1899, located 40 km southeast of London. Wingham had a comparable population and was located 115 km north of London, while Dutton was a village in 1899, 40 km southwest of London. Owen Sound, with a population of 8,500 in 1899, was the largest centre to publish the ad, and the furthest distance, about 200 km north of London. Clearly the company's advertising campaign would have reached few potential buyers.

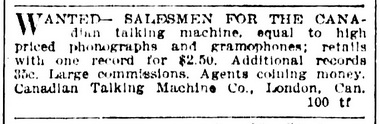

On April 28, 1899, the CTMCo ran a small ad in the classified section of the Globe (Toronto) newspaper, and simultaneously in the Montreal Star, soliciting salesmen for their product. In a flurry of activity to capture the attention of the phonograph buyer, they repeated the ad in the Toronto newspaper on April 29, May 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 8, 9, 10, 11 and in the Montreal newspaper on May 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8 and 10.

WANTED - Salesmen for the Canadian talking machine, equal to high priced phonographs and gramophones; retails with one record for $2.50. Additional records 35c. Large commissions. Agents coining money. Canadian Talking Machine Co., London, Can.

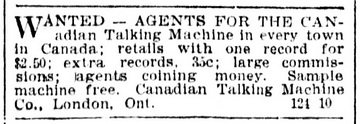

In a second burst of activity, a slightly different classified ad ran 9 times only in the Montreal Star, beginning on May 29, 1899, and repeated on May 30, 31, June 1, 3, 5, 6, 7 and 8.

WANTED - Agents for the Canadian Talking Machine in every town in Canada; retails with one record for $2.50; extra records, 35c; large commissions; agents coining money. Sample machine free. Canadian Talking Machine Co., London, Ont.

While the classified advertisements in the Montreal and Toronto newspapers appealed for salesmen and agents "in every town in Canada", and one can't help chuckling at their enticement, "agents coining money", the company never ran the display ad, that included the drawing of the machine, in these major cities. The display ad only mentioned "Agents wanted in every town and village". Were advertising rates too expensive in major city centres? At $2.50, the Canadian Talking Machine was an extraordinary bargain. Perhaps the company gambled that it would most likely find its customer base among the populations of rural Ontario?.

1st classified ad for the Canadian Talking Machine

Montreal Star, May 1, 1899, p. 6

|

|

2nd classified ad for the Canadian Talking Machine

Montreal Star, May 29, 1899, p. 6

|

|

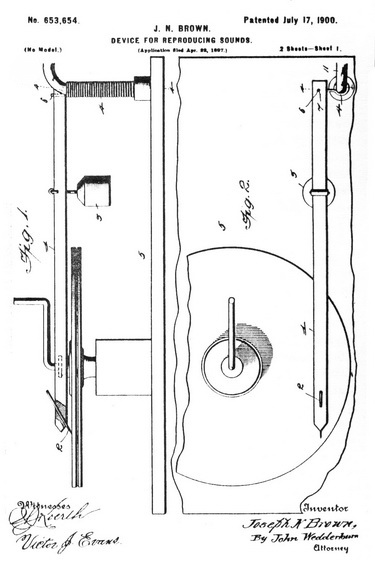

The Canadian talking machine is a finger-wind disc machine. The idea of such a simple device was in the air at the time. On April 22, 1897, Joseph N. Brown (1848-1913), who was born in Canada (Ontario), emigrated to the U.S. about 1863 and was living in Muskegon, Michigan, filed an application for a U.S. patent titled "Device for Reproducing Sounds". The patent was issued three years later on July 17, 1900, as U.S. patent no. 653,654. The distinguishing feature of Brown's device, illustrated in two patent drawings, was a solid wood tonearm, firmly-mounted steel needle and a sliding weight, identical to the tonearm assembly depicted in the drawing of the Canadian machine. No model was submitted with the patent application. The patent description noted that the invention was applicable for the reproduction of sounds recorded on both gramophone discs, illustrated on page 1 of the application, and phonograph cylinders, illustrated on page 2, and could use either listening tubes or a horn.

U.S. Patent No. 653,654, p. 1

|

|

U.S. Patent No. 653,654, p. 2

|

|

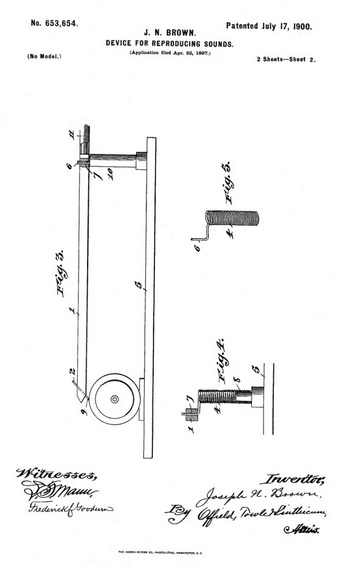

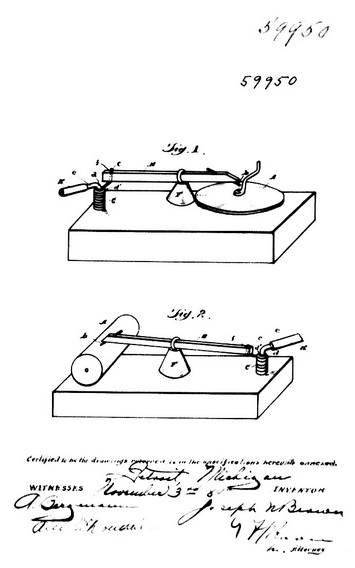

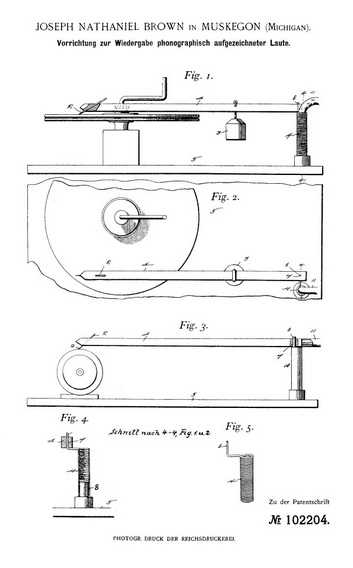

Seven months later, on November 8, 1897, Brown applied for patent protection in Canada. Canadian patent no. 59950 was issued on May 10, 1898. The Canadian patent application included drawings of the device as both a disc machine and a cylinder machine together on the same page. The only significant difference between the U.S. and Canadian patent drawings was the shape of the sliding weight.

On March 1, 1898, Joseph Nathaniel Brown applied for a German patent which was issued on March 21, 1899. The patent drawing combined on one page the drawings presented on two pages in the U.S. patent. The shape of the sliding weight corresponded to the weight in the U.S. patent drawing. There is no record of any production or marketing of a machine in Germany based on the patent. One interesting observation is that only the Canadian patent drawing showed a weight on the cylinder version of the design.

The principle of the sound reproduction from the device was simple, although Brown was unwilling to fully divulge the secret in the patent descriptions. As the needle tracked a disc or cylinder record, vibrations were transferred through the wood bar to a coiled spring which was pushed through the end of the bar. A listening tube, inserted into the coiled spring, reproduced the sound waves from the vibrating spring.

Canadian Patent No. 59950

|

|

German Patent No. 102204

|

|

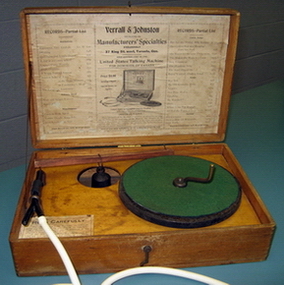

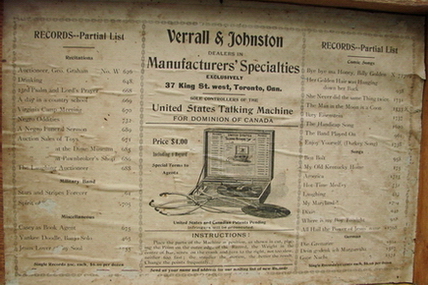

Some time after Brown filed for his U.S. patent, he approached the Berliner Gram-o-phone Company to arrange for a supply of records to be used on the device. His request was transferred to Frank Seaman's National Gramophone Company, the exclusive sales agent for Berliner’s Gramophone and records, and its president, Orville La Dow. Without objection, Brown's request was granted, a contract was executed and a quantity of records was sold to Brown. His device was put on the market in January, 1898, as the United States Talking Machine by the newly-formed United States Talking Machine Company (USTMCo) of Chicago, incorporated by T.C.and G.H. Mosely, priced initially at $3.00, later increased to $3.50. One of the early ads, published in February, 1898 in The Phonoscope, a monthly journal devoted to scientific and amusement inventions, showed a shallow, rectangular wood box housing a turntable, a vertical hand- or finger-wind mechanism, a horizontal wood tonearm with a central hanging weight and a steel pin or needle at one end, a coiled spring and a support for two listening tubes. A paper graphic that covered the inside lid listed current 7" Berliner discs that could be played on the machine. The United States Talking Machine was the first non-Berliner disc-playing talking machine for sale to the public.

United States Talking Machine

The Phonoscope, February, 1898, p.13

|

|

Seaman may have actively marketed the machine through his sales network or he may have simply supplied records to the USTMCo. Some late examples of the machine carried the name of the National Gramophone Company on the paper label. What was unusual was that the Berliner Company actively supported the USTMCo. Berliner was known to brook no competition in the disc talking machine market. The company ferociously went after any product that appeared to infringe on its patents but, in this instance, it must have considered a finger-wind device trivial competition for the contemporary spring-wound Berliner Improved Gram-o-phone, and decided that supporting an innocuous competitor was a timely opportunity to sell more records.

Similarly the CTMCo likely had an arrangement with the Berliner company to supply Berliner discs with its machine. The February, 1900 Montreal Star announcement of the Berliner Gram-o-phone in Canada advised that

all other talking machines using HARD PRESSED FLAT RECORD DISCS are sold without authority and are infringements of patents 55078-55079 and the public is cautioned against buying such infringing machines.

The December 1898 press releases for the Canadian Talking Machine mentioned that

The records are made of vulcanized rubber and are practically indestructible.

This should have drawn the ire of Berliner, and an eventual lawsuit, but no court action between the two companies was reported in the Canadian press.

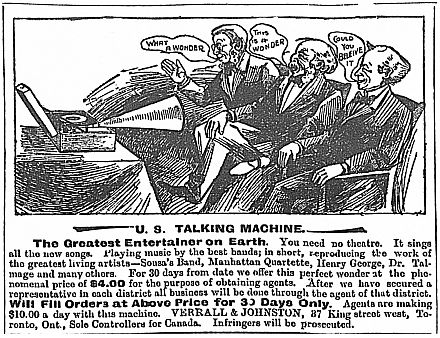

The Globe, April 23, 1898, p. 22

|

|

The Globe, April 9, 1898, p. 26

|

|

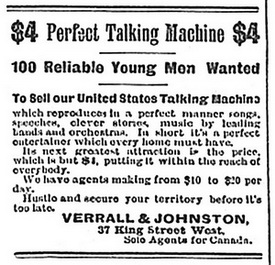

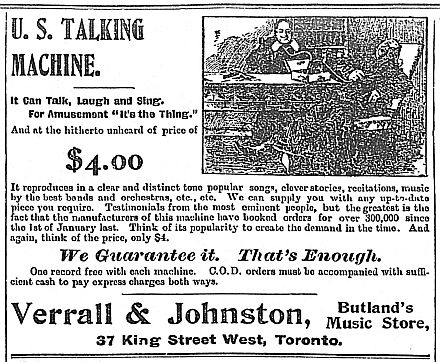

The United States Talking Machine Company expanded briefly into Canada, advertising their product four times in the Toronto Globe newspaper. The first ad on April 9, 1898 sought to enlist "100 reliable young men" to sell their "Perfect Talking Machine". The second ad on April 23 showed a United States Talking Machine, "the greatest entertainer on earth", with a horn, entertaining an amazed group of Canada's finest including, on the left, Sir Oliver Mowat, Lieutenant-Governor of Ontario, and on the right, Sir Wilfrid Laurier, Prime Minister of Canada. A display ad on April 30, which was repeated on May 11, the day after the Brown Canadian patent was issued, borrowed a current Columbia Graphophone graphic and substituted a U.S. machine with listening tubes. The seller of the United States Talking Machine, "the sole agent for Canada", was Verrall & Johnston, Butland's Music Store, 37 King Street West, Toronto and while the U.S. and Canadian currencies were on par through the 1890s, it was sold in Canada for $4.00, a 15% markup on the current selling price in the U.S. Note the preposterous sales figures in the May 11 display ad: "the manufacturers of this machine have booked orders for over 300,000 since the 1st of January last".

The Globe, May 11, 1898, p. 4

|

|

Nevertheless, the finger-wind United States Talking Machine was not a success - it was essentially a child's toy - and was soon discounted and even offered as a free premium in the U.S. One ad by the Knowles & Gardiner Co., Main St., Buffalo offered "$3 talking machines in hard wood cases for 59 cents." (Buffalo News, December 20, 1900, p. 8) We have found no discount ads for the machine in Canadian newspapers.

The similarities of the essential features of the Canadian Talking Machine to the Brown patent and, by extension, to the United States Talking Machine, are readily apparent. The December 16, 1898 newspaper announcement of the Canadian machine even mentioned that "the patent was secured last May", which coincided with the issue date of the Brown patent in Canada on May 10, 1898. This was clearly the patent acquired by Mercer to enable him to market his talking machine in Canada.

One possible scenario: Mercer, the newly-appointed manager of the London branch of the Bell Organ & Piano Company, became aware of the United States Talking Machine, saw an opportunity and purchased the patent for the finger-wind device from Brown. When the USTMCo began to fail by mid 1898, he made arrangements to manufacture and market a different design of the machine in Canada, at a lower price, which he called the Canadian Talking Machine. A simpler scenario would have the USTMCo marketing a new design of their machine in Canada, through Mercer, under the name Canadian Talking Machine as sales of its boxed unit faltered in both countries. We may never know the full story.

The Canadian model of the United States Talking Machine carried a distinctive label on the inside of the lid

identifying Verrall & Johnston, Dealers in Manufacturers' Specialties exclusively, at 37 King Street West, Toronto,

as the sole controllers of the United States Talking Machine for the Dominion of Canada.

Courtesy of Domenic DiBernardo

|

|

|

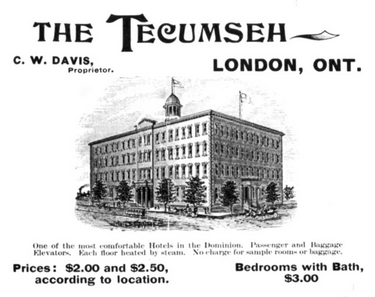

A search for Lawrence Grant Mercer (1857-1919), owner of the Brown patent in Canada, found him setting up and then managing the Windsor showrooms of the Bell Organ & Piano Company in October 1897. By April, 1898, he was the manager of Bell's London Warerooms, 167 Dundas Street, London, while boarding at The Tecumseh, "one of the most comfortable Hotels in the Dominion". A search through several London city directories for 1898-1899 failed to turn up a listing for the CTMCo. An unsolicited testimonial of the Bell Orchestral piano in the Montreal Gazette in October 1899 found Mercer at 2263 and 2303 St. Catherine St., Montreal, in close proximity to the Berliner store at 2315 St. Catherine, where he now managed the Bell Piano Company in that city.

Foster's London City and Middlesex County Directory

1898-1899

|

|

By 1900, Mercer apparently had a change of career. In June, 1900, he was mentioned in the Montreal Gazette at Riverside Park, the Coney Island of Canada, situated at Rue de Maisonneuve, opposite a vaudeville theatre. Described as an amusement director, he had engaged a vaudeville company from the New York Roof Gardens for a series of performances. In August, 1903, Lawrence G. Mercer was mentioned in Billboard as the manager of a dramatic theatre company performing in Chicago, and in 1918, the year before his death, he was in New Orleans for the winter season. Mercer was married twice, first to Nora in 1883 at Niagara Falls, and second to Inez in Louisiana. Only the second marriage produced a surviving child, Gladys.

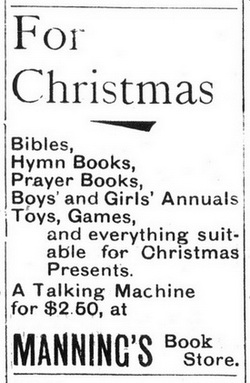

The Canadian machine suffered the same fate as its U.S. counterpart. It was advertised and on the market for only a brief period: two initial press releases in December, 1898, followed by a single unique display ad which ran numerous times in at least six small-town Ontario newspapers between February and September, 1899, and two classified ads in April, May and June in the two major Montreal and Toronto newspapers. While the September 28, 1899 display ad in the Aylmer Express was the last ad that we found for the company, the Canadian Talking Machine was still available in December of that year. On December 12, 1899, Manning's Book Store in Ingersoll, Ontario, 40 km east of London, advertised "A Talking Machine for $2.50". This must have been the Canadian machine, still offered at full price. Two days later on December 14, a notice appeared in the Aylmer Express that a Bert C. Wales had been appointed agent for the CTMCo, and the machines were obtainable at his store at the bargain price of $2.00.

Despite the hyperbole of 15,000 machines ordered by a Buffalo firm for the Australian market, there must have been few sales and all or most of these must have occurred in rural southern Ontario. Where are they now? The Canadian Talking Machine is not mentioned in Roll Back the Years, Edward Moogk's History of Canadian Recorded Sound and Its Legacy, nor is it documented in any of the literature on phonographs and phonograph collecting - From Tin Foil to Stereo to the present day. Exhaustive searches through contemporary newspapers published in Ontario towns and cities have turned up very little original ephemera. All of it is presented in this article. For the moment, there are no known examples of the machine in any phonograph collection. It is an unknown chapter in the history of North American phonographs.

Not identified by name, but a Talking Machine for $2.50 must have been the

Canadian, still available in late 1899.

Ingersoll Chronicle,

December 12, 1899, p. 1.

|

|

The original impetus for this research project was a search for the earliest talking machine made in Canada. Have we succeeded in that search? Unless an original packing box for the Canadian Talking Machine is found, labelled "made in Muskegon, Michigan", there is no direct evidence that it was made in the U.S. or that it was merely assembled in Ontario from the remnant parts of the United States Talking Machine. On the contrary, there are compelling reasons why it was likely made entirely in Canada.

While the salient components of the Canadian and United States machines were strikingly similar - finger-wind mechanism, wood tonearm with slanted needle and sliding weight - and their construction was clearly based on the same patent, the overall designs were quite different. The U.S. mechanism was enclosed in a lidded wood box measuring 11 1/2 x 8 1/2 x 3 1/2 inches while the Canadian mechanism stood on a tripod base and, according to the December 16, 1898 article, was sold "packed in a box 15 inches long, 7 1/2 inches wide and 2 3/4 inches deep." Except for one rare depiction in a Canadian ad using a horn, the United States machine was sold with listening tubes while the Canadian machine came with a 15 inch horn.

The December 28, 1898 newspaper report on the Canadian Talking Machine in the Windsor Star claimed that it was "made in London". The earlier December 16 press release in the London Advertiser was even more explicit and claimed that it was "manufactured in the city of London". Are we to dismiss these claims as exaggerated or fabricated?

Why would Mercer have acquired the patent - the newspaper articles reported that he "owned" the patent - if he had not intended to manufacture a talking machine locally under patent protection in Canada? A restless and ambitious man, Mercer worked for a company that had been manufacturing one of the premier pianos in Canada for 35 years. He would have recognized the advantages of local production and had access to the resources of a major piano factory. He may have used their facilities, or at least their expertise, or he may have struck out on his own to get in on the ground floor of the nascent talking machine industry.

Aylmer Express, December 14, 1899, cover

|

|

In a letter to The Phonoscope in March, 1897, Brown revealed that the total cost to manufacture his machine was but 12 1/2 cents each, complete. Would Mercer have needed to import a needle, a sliver of wood and the other inexpensive components for such a simple device? Any one of the many piano and furniture factories in close proximity to London, Ontario, could have supplied these parts as well as the small metal turntable and distinctive tripod base. The tariff on American goods imported into Canada during this period was 25-35%, an excellent incentive to manufacture locally. If the machine, as designed, were available in the U.S., why would a Buffalo firm have contracted to buy 15,000 units from the Canadian company? Would they not simply have contracted with the American supplier, if there were one?

Unlike the "made in Canada" Berliner Gram-o-phone, which was only partially constructed in Canada beginning in 1899, the Canadian machine appears to have been wholly manufactured in Canada by mid to late 1898, six to twelve months earlier than the Berliner machine. Despite its brief appearance on the market, and until and if research uncovers an even earlier product, the Canadian Talking Machine, manufactured in London, Ontario, in 1898-1899, by the Canadian Talking Machine Company, appears to qualify as the earliest commercially "made in Canada" talking machine.

References

- "The Patent History of the Phonograph 1877-1912", Allen Koenigsberg, APM Press, 1990

- "The Gramophone Becomes a Success in America, 1896-1898", Raymond R. Wile, ARSC Journal, Volume 27 No. 2, Fall 1996

- "Discovering Antique Phonographs 1877-1929", Timothy C. Fabrizio and George F. Paul, Schiffer Publishing Ltd., 2000

- "The United States Talking Machine", George F. Paul, The Sound Box, Vol. XXII, No. 2, June 2004

- "Tracking Down (and Naming) the 'Civil War Vocophones': What Were They?, Allen Koenigsberg, The Antique Phonograph, September 2023 (pre-publication)

- Newspapers.com: https://www.newspapers.com/

- The Ancestor Hunt: Ontario Online Historical Newspapers Summary: https://theancestorhunt.com/blog/ontario-online-historical-newspapers-summary/

Acknowledgements

I sent a first draft of my article to Allen Koenigsberg for comment on my early Canadian "find". By an amazing coincidence, he had just submitted an article for publication in The Antique Phonograph that referenced the exact same Brown U.S. patent, 653,654, quoted in my article. The idea of a finger-wind talking machine was, indeed, in the air. I am indebted to Allen for steering me to the United States Talking Machine Company and its connection with the Berliner Company, for tracking down the Canadian and German patents and for other historical details in my article. Thank you to Stephan Puille for supplying the German patent drawing of Brown's invention.

|