|

Edward B. Moogk

The Grand Old Man of Canadian Recorded Sound

Personal Reminiscences by Paul Dodington

As was the case with a great

many of those who knew him,

my first acquaintance with Ed

Moogk was through his legendary

CBC radio program Roll Back The

Years, to which I listened religiously

every week as a boy of 10. As a budding collector

of things phonographic,

I was astounded not only with Edís vast

knowledge of the whole field of early

recorded sound, but with his ability to

present his material week after week in

an interesting and humorous manner.

Edward B. Moogk (1914-1979)

|

|

We corresponded by mail from

time to time and I still treasure some

78s he sold to me as early as 1951. It is indicative of

Edís personal warmth and desire to share his enthusiasm

with anyone of like interest that such a great personality

should choose to spend his precious free time writing

replies to a mere child. Our 25 year discrepancy in

chronological age apparently meant nothing to him and

as time passed it came to mean nothing to me as well.

We did not meet personally, however, until about

1962, when Ed was Director of Public Service for CFPL

Television (London, ON). A mutual friend took my

then-fiancee, Nora and myself to the Moogk home on

Hibiscus Avenue one afternoon, where we were warmly

welcomed by Ed and his wife Edith, and introduced to

their 3 lively children, Janet 15, Debbie 13, and George

11. It was on this day that our acquaintance truly blossomed

into friendship and regular visits back and forth from

the Moogk residence to the Dodington residence in

Toronto became joyful events in all our lives.

Strangely enough, the final barrier was not yet broken

down. We, like others, had always known him as Ed

Manning, but on our second visit to Hibiscus I happened

to notice a letter addressed to Edward B. Moogk (pro-

nounced Moke) lying on a desk. It was then that I came

to realize that as a Canadian of German extraction, he

had found it advisable, at least in his public persona, to

"anglicise" his unusual surname. This

he had done during the 1940s to

avoid awkward situations and perhaps

downright unpleasantness. It was a

common practice since prejudice was

indeed rampant in those days!

We were both relieved after I began

to call him Ed Moogk instead of Ed

Manning, and our relationship from

that time on was characterized by an

openness and lack of pretension which

we both treasured.

Ed had grown up as the third son

in his family and like many younger

sons he had developed a bit of an

inferiority complex in relation to his two successful

older brothers, Ernie and Willis, both of whom eventually went on to distinguished military careers as Captain

and Brigadier-General respectively. As our friendship

deepened, I began to realize that Ed,like other public

personalities, had found it prudent to erect a protective

veneer about himself and his family. This was done in

part to become more acceptable to his audience and

particularly to what he perceived to be the anglophone

ruling majority in Ontario, but I think also to convince

himself that he was just as successful as his two brothers.

Most of us remember his public image ó Ed

Manning, the impeccable dresser with the meticulous

grooming, driving the big, flashy cars. But those

of us who were privileged to know him better could get beyond

all the trappings and appreciate the real Ed ó a man of

great generosity, sensitivity and openness. He had an

almost child-like enthusiasm for just plain goofing off

and having fun, without ever going beyond the bounds

of good taste.

His interest in recorded sound began in early

childhood in Weston where his father had a windup

gramophone and the usual assortment of records. After

his parents passed away and he went to live with his

maternal grandfather, John Grasser, in Kitchener in

1934 the records went with him. It was here that his life-

long interest in jazz and Big Band music began to flower.

He became an accomplished drummer, eventually playing

in the Bob Donelle and Willis Tipping dance bands.

Ed and Edith Moogk

|

|

(CAPS member) Gerald Parker recounts a marvellous

Ed Moogk story: At a Canadian Collector's

Congress annual meeting (Ross)

Brethour played a segment from this disc featuring the dance

band of which Ed was a member between 1940 ó 1942,

the anthology being "hot off the presses" and thus new to

those present, during a mischievous "guess who" musical

quiz. Asked to identify the "mystery drummer" of the band

the astute and well-informed attendees desperately guessed

celebrities from George Wettling to Gene Krupa ó the

playing was that good ó and consternation reigned when

Brethour revealed to all assembled that Ed Moogk, sitting

in their midst was the drummer. Such a grin on Edís face

such a chuckle!

I believe that it was through his dance band involvement that he met and in 1939 married Edith Howell of

nearby Doon, Ontario, who was three years his junior.

She remained all his life a warm and faithful supporter

of her husband in all his activities, professional and

otherwise. Her personal day-by-day sacrifices are an

unrecognized part of the development of both Edís

professional career and his enormous record collection.

In the years immediately after World War II Ed

amassed much of his documentary material and became

personally acquainted with countless early recording

artists and technicians, a rapidly vanishing breed. Most

of these,like aging movie stars, were long since forgotten

and languishing in retirement. Such luminaries as Billy

Murray, Reinald Werrenrath, Charles Harrison and Elsie

Baker became personal friends, and Ed even managed to

persuade the occasional one, like Charlie Harrison, then

in his 70s,to re-record some of his old chestnuts for the

Gavotte label, which Ed had established during his years

with the Gordon V. Thompson Publishing Company

in Toronto. Ed and Edith were invited as weekend guests

on more than one occasion to the Reinald Werrenrath

mansion in the Thousand Islands, where guests were

expected to appear for dinner in formal dress and to

address their host as Doctor Werrenrath!

On another occasion in the early 1950s, a reunion of

early acoustic recording artists was arranged (probably in

New Jersey) and Ed's stories about the characters that

showed up were truly marvellous: Elsie Baker made a

grand entrance wearing an enormous hat of Edwardian

vintage, Billy Murray poking fun at all the ladies, and so

forth. It was at once a joyous but tearful event, and sadly

the last time that many of them ever saw one another.

Ed was as much interested in the personalities of the

early recording days as in their accomplishments. When

he visited Billy Murray at his Freeport, Long Island home

in the fall of 1950 he discovered that Murray was a man

of deep religious convictions, a rather surprising revelation when one considers his recorded legacy. Murray

was still going strong, singing as a tenor soloist in one

of the large churches in New York.

Ed's friendship with Herbert S. Berliner of Montreal

was of long duration and one of his favourite phonographic jokes came from Berliner: Young son asked his father, "Father, did Edison invent the first talking

machine?" To which his father replied, "No, my son, God

invented the first talking machine but Edison invented

the first one that could be shut off".

During the mid-1960s Ed occasionally visited Toronto

to attend meetings of such esoteric societies as the

Mississauga Jazz Muddies. He generally stayed at our

home, and naturally these visits invariably degenerated

into a veritable cacophony of non-stop cylinders and

discs, which we would play "at" each another. Our wives,

who usually exhibited a superior sense of decorum, gave

up in disgust on such occasions and withdrew to saner

surroundings. Ed had always been plagued with bad

luck in his dealings with mechanical devices, and early

phonographs, especially cylinder players, were a constant

source of trouble although he

enjoyed the records. It was a

source of amazement to him that

my early phonographs worked

flawlessly (I never did reveal to

him that this was not always the

case) and that early recordings

could sound so good. One day,

he gave me his entire collection

of about 600 cylinders along

with a decrepit, but potentially

gorgeous Edison Triumph Model

D complete with Model O

Turnover Reproducer;

all with absolutely no strings attached. I

was dumbfounded. "I think you'll get more out

of this stuff than I ever will" he said. Such was his generosity.

Nora and I brought the precious cargo home in our

venerable 1950 Pontiac in a harrowing 7 hour trip from

London to Toronto in an ice storm.

In August, 1964, Ed's plan of forming a national collection

of sound recordings of Canadian content was first presented to the Centennial Commission. I was honoured

to be asked by Ed to be among those to support the

proposal and to advise the commission as to its validity.

The rest, as we know, is history, and it eventually came

to pass that the collection of recorded Canadiana so

amassed became established within the mandate of the

National Library (of Canada). Edís vast personal collection of Canadian material became its nucleus, and many

of Ed's friends and colleagues, including myself, simply

opened up our collections to him and gave generously

of our treasures to support the cause.

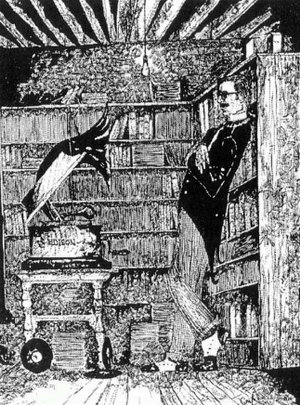

A caricature of Ed Moogk drawn by his son, George (ca.1970)

|

|

When Ed was appointed curator of the Recorded

Sound Division in 1972, the resulting move to Ottawa

naturally made personal contact with his Toronto and

Western Ontario friends a bit more difficult to maintain.

Nevertheless, Nora and I did participate in a number of

the Ottawa events, including the launching of his book,

Roll Back The Years published in

English and French versions by

the National Library in 1975.

We also provided many

of the display items for the exhibition

celebrating 85 years of Recorded

Sound in Canada. And again in

1977 we provided phonographs,

records and ephemera fora special

display which Ed organized at

the Canadian National Exhibition

in Toronto, celebrating 100 Years

of Recorded Sound.

Meanwhile interest in

recorded sound had been reaching

unprecedented heights, largely because of Edís publicising

of this esoteric field

of interest. In 1970, when he learned

that a few of the old record buffs in Southern Ontario

were about to establish a formal society, he gave much

advice and encouragement to the fledgling organization

and became one of the charter members of the Antique

Phonograph Society, later known as CAPS. Ed himself

became a charter member and gave one of the first presentations

ó the story of the Berliner Gram-O-Phone

Company of Montreal.

The years from 1972

ó 1979 that he spent at the

National Library were rewarding, if lonely ones for the

Moogks. By this time of course the children had all been

launched on their various careers, and Ed was at long

last receiving due recognition as one of the worldís foremost authorities on early recorded sound. (Ed was made a

member of the Order of Canada in 1975.) And yet, I could

sense as time went on a growing disillusionment with the

civil service nature of the job and that both he and Edith

were looking forward with anticipation to his retirement.

I well remember the weekend in 1979 when Nora

and I helped the Moogkís move his personal record collection from Ottawa back to London, Ontario where they

had purchased a new home. Because so many of his

priceless discs had been damaged by professional movers

in the earlier move to Ottawa, I had convinced Ed that it

might be better to rent a van and that Nora and I, along

with Ed, Edith and their children would do the job.

Hundreds of empty liquor cartons had been scrounged

from LCBO outlets and the records had been carefully

stacked therein by Ed and Edith during the preceding

weeks. As we began loading up the rental van,it soon

became apparent that the vehicle was a bit undersized

in terms of carrying the incredible weight. This was solved

(or so we thought) by inflating the tires to 50 psi, far

above the maximum rating, and even then they bulged

ominously. All of our automobiles were subjected to

the same overloads, and by about 10 a.m. on a bright

June morning, Edís record collection was trundling

along on its way to London.

Just west of Kingston, the inevitable happened. The

left rear tire blew to pieces and we careened to a sudden

stop on the shoulder. George Moogk, who had been

following close behind, took the wheel to a nearby garage,

where a new tire was fitted.

The full moon was high in the sky that evening

when the caravan finally arrived at the Moogkís new

home on Wilkins Street, and the last of the precious

boxes were unloaded. We had completely filled the

basement floor from end to end. To the best of my

knowledge not one record was damaged in transit, but

we had all aged considerably. After a good night's rest,

and one of Edithís legendary breakfasts, we all agreed

that it had been a once-in-a-lifetime adventure and that

we would not have missed it for worlds.

In the interim, since publication of Roll Back The Years,

Ed had been working away at a sequel, which was to

cover the period from 1930 to the end of the 78 rpm era.

But he had other smaller projects on the go as well, and

of these his favourite was to write a history

of the Anglo-Canadian Leather Co. Band of Huntsville, Ontario.

This organization, although it never made a formal

sound recording, gained an international reputation as

one of the finest concert bands during the period 1917-

1922 under the baton of renowned Sousa cornetist and

assistant conductor, Herbert L. Clarke.

Clarke, along with several other luminaries from

Sousaís band, had been lured up to the northern backwoods of Canada by the owner of the local tannery,

Charles Orlando Shaw, himself an amateur cornetist.

The demand for leather for boots, harness and other

military equipment had risen to unprecedented heights

because of the war in Europe, making Shaw a very

wealthy man. Most of his tannery employees had been

recruited from Italy in the early years of the century as

cheap labour. The local police chief had pleaded with

Shaw to provide some sort of activity to keep all these

young bucks from tearing up the town every Saturday

night. Shaw, assuming that all Italians were by nature

musicians, therefore established a company band about

1908, with himself, of course, as cornet soloist. By 1917,

when Clarke and his colleagues from Sousa were hired,

at astronomical salaries, the band was already an established fact. Under Clarke's direction the Anglo-Canadian

Band developed a world-wide reputation in spite of the

fact that it never recorded and never ventured further from

Huntsville than to the Canadian National

Exhibition in Toronto, 140 miles to the south. Such was its reputation,

that Major J. Mackenzie-Rogan,

M.V.O., Mus.-Doc.,

Hon. RAM. leader of the band of H.M.Coldstream

Guards made a special trip to Huntsville to observe and

to conduct this legendary concert band.

Ed Moogk

|

|

Nora and I had moved from Toronto to Port Carling

in Muskoka, not far from Huntsville, in 1976, and had

gained some intimate knowledge of the area and its

history, so it was only natural that when Ed and Edith

came to visit us for a week in September 1979 we should

actively pursue Edís Anglo-Canadian interest.

While Edith and Nora spent their days enjoying

each other's company and caring for our two young

daughters, Ed and I were off bright and early each

morning to Huntsville

researching and interviewing

the half-dozen surviving members of the Anglo-Canadian

Band. One of these wonderful characters was still living

in the old octagonal bandstand which he had helped

build in 1908. After the band folded in the mid-20s, he

bought it and converted it into his residence.

By the end of the week, Ed and I had together

managed to amass a considerable collection of tape-

recorded interviews and photographs, as well as sheaves

of notes. We had visited the local pioneer village, which

houses considerable Anglo-Canadian memorabilia, and

had even surreptitiously peeked in the parlour window

of Herbert L. Clarke's substantial home overlooking

Hunter's Bay to see the screw eyes in the ceiling from

which the great cornetist suspended his instrument on

wires while practising his technique.

After dinner at home each evening we took a trip

in our 1903 vintage steam launch, Constance, among

the island-studded waters of Lake Rosseau, visiting such

lovely century-old hotels as Clevelands and Windermere

House. Returning home after dusk there would begin a

non-stop session of early recordings until utter exhaustion

imposed a reluctant finish to another day. It was an idyllic

week of joyful activity for us all, and it was with heavy

hearts that we said goodbye when the Moogks returned

to London. Little did any of us suspect that it was all

over. We would never see Ed again.

Less that two weeks later, he suffered a ruptured

aneurism behind his knee, and his leg eventually had to

be amputated. Most of the autumn of 1979, he spent

in a semi-conscious state in hospital, where his condition

gradually deteriorated. The Moogk family drew together

for mutual support during the crisis, and when we

heard from Edith on December 18th that Ed had died,

I immediately regretted not having gone to see him in

spite of his "no visitors" request. It was important to him

to maintain his personal dignity to the end.

At first, Nora and I felt a degree of personal responsibility for hastening the onset of Edís demise. For some time he had been overweight and in poor physical condition, and in retrospect we should have made

allowances for this. When the Moogks visited us in

Muskoka that week, should we have been a little less

enthusiastic in encouraging his Anglo-Canadian project?

Should our activities have been less physically demanding?

After Ed's passing, Edith, suspecting our feelings

of uneasiness, revealed to our surprise that the summer

of Ed's retirement had been a period of depression and

lethargy for him. Of course, this is frequently the case

when one retires from oneís career activities at age 65.

She reassured us that the week in Muskoka had had the

salutary effect of revitalizing Edís youthful

exuberance, and had re-awakened his usual interest in research and

life in general. She insisted that none of us should harbour any feelings of guilt or regret, and assured us that

Ed had spent that week exactly as he would have wished.

Edith requested that I sing at the memorial service

which was to be held at Hamilton Road Presbyterian

Church in London, but I suggested that in this

case it might be much more appropriate to play a suitable

vintage Canadian record on an early horn gramophone,

an idea which she readily accepted.

The service was well attended by his friends and

associates from the many areas of Ed's multifaceted career,

as well as by his close and extended family. For the musical

tribute,

I provided a Victor V Talking Machine with oak

horn on which was played Herbert S. Berliners fine

recording of Toronto baritone, Frank Oldfield singing

Arthur Sullivan's The Lost Chord. It was a selection

which proved touchingly appropriate to the occasion.

I believe that Ed would be gratified to see the bountiful

harvest of the seeds which he sowed during his lifetime

across the whole field of historic recorded sound. Certainly

in Canada his influence has been greater than that of any

other single individual. In his own unassuming way, he

managed to quietly link up Canadian collectors, and give

them, through his programs, his writings, and his personal encouragement, a focus to their individual activities.

He was fiercely proud of the countless contributions of

Canadians ro virtually every aspect of recorded sound and encouraged

us all to recognize, respect, and preserve that important legacy.

He even went so far as to say that

the phonograph itself would have been a Canadian

invention, had Edison's Canadian-born father not gotten

himself mixed up in the 1837 "comic opera" political

rebellion, which forced him to seek asylum in the USA.

But while Ed, by his own example encouraged

scholarly research, he never once lost sight of one essential

fact: collecting, owning and playing old records and using

old phonographic equipment is fun. He was well aware

that in the great melting pot that we call time,the things

that survive are those which embellish the human spirit,

and which continue to bring joy and inspiration to

succeeding generations. I believe that Edward Balthasar

Moogk, in the tradition of his biblical namesake, showed

us by his own example that through our own personal

enthusiasm we must preserve and interpret our rich

recorded sound legacy, and seek new ways of keeping it

all relevant for the enlightenment and enjoyment of

generations yet to come.

The author wishes to thank Barry R. Ashpole, and also

the three Moogk children, Janet, Debbie and George

and their families for their enthusiastic and invaluable

assistance and advice in the preparation of this article.

Bibliography

- Parker G. Edward G. Moogk. Obituary and Personal

Reminiscences. ARSC Journal 1979;11(2-3):97-99.

- Ford C. and Kallman H. Moogk, Edward B. Encyclopedia

of Music in Canada Toronto, on: University of Toronto

Press, 1985 page 882.

- Barriault J. and Jean S. Moogk, Edward B., 1914-1979

Catalogue ofthe Archival Fonds and Collections of the Music

Division (National Library of Canada) Ottawa, ON: 1994.

|