|

The Vitaphone Project

by Barry R. Ashpole

The Vitaphone Project is an ambitious

undertaking by a group of U.S.

collectors to recover and restore — and hopefully see re-issued — what remains of a priceless legacy

from the earliest days of the film and sound recording

industries. The project takes its name from the Warner Bros.

Vitaphone studios which produced by far the greatest

variety of "film shorts". Following is a condensed version

of the authors presentation to the CAPS meeting April 2nd.

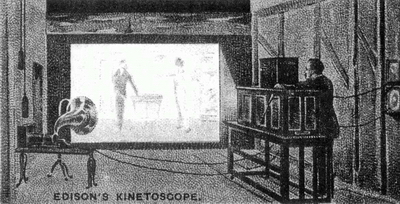

Edison's Kinetoscope

|

|

The first "talking pictures" to be a viable, commercial proposition in North America comprised of two distinctly separate elements: the

image on a single reel of celluloid film, and the sound

on a 12-inch or 16-inch shellac disc. Of the many thousands of these "filmshorts" produced during a ten-year

period beginning in 1926, only a handful survive complete. Lost or destroyed are one or both elements.

Gone are countless memorable performances by artists

of the day, some of whom made no other form of

commercial recording.

Poor quality sound and imperfect synchronization

plagued the first attempts at "talking pictures".

In 1889, Thomas Alva Edison introduced the

Kinetophone. Edison produced a series

of films with

sound, using a large, longer than standard-playing

Amberol cylinder. But the only thing synchronized

about the Kinetophone was that the film and the

cylinder started and stopped at the same time! In 1913,

Edison offered theatre owners a new and improved

Kinetophone (Fig. 1), but its success was short-lived.

The inventor had still not overcome the basic problem

of synchronization, and theatre owners were inclined

not to invest in additional and costly equipment to use

the Edison system. Only 45 Kinetophones sold.

At about the same time, Lee De Forest made the

first of his attempts, applying technology he had developed to improve detection of wireless telegraph signals. In 1919, Theodore Case used a mirror attached to a

diaphragm as a means of capturing sound within the

site of the margin of the film to develop in his

Movietone system the first "sound track". De Forest

was to improve on this system and in 1922 he produced

his first Phonofilm. It was the first commercial "talking

picture", and by 1925 De Forest had produced a number

of Phonofilms featuring popular performers, among

them Eddie Cantor. De Forest and the Phonofilm,

however,failed, due primarily to lack of capital.

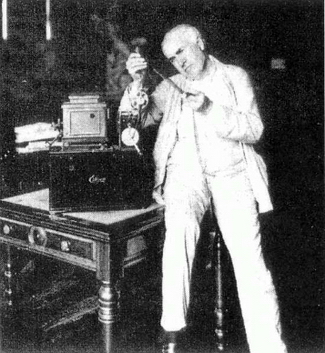

Fig. 1: Thomas Alva Edison examines a reel of Kinetophone film (circa 1913).

|

|

Few theatre owners expressed any real interest or

enthusiasm for the first "talking pictures". They considered "talkies" no more than a novelty and that the

cost of rewiring a theatre for sound not worth the

investment. Silent films were firmly entrenched. Harry

Warner, of Warner Bros. Pictures, echoed the views of

many critics and skeptics when he was quoted as saying:

"Who the hell wants to hear actors talk?"

Bell Telephone Laboratories, through its subsidiary

Western Electric, was looking for a foothold in the film

industry. By mid-1925, its electric recording process

had been adopted by the major recording companies —

Brunswick, Columbia and Victor. With minor modification, and building on the experience and expertise of

De Forest and others, the electric recording process

was adapted to provide quality sound and improved

synchronization using a disc-based sound system.

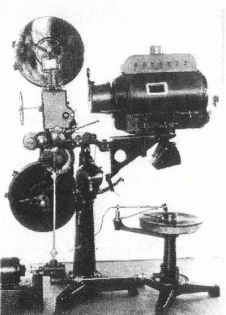

The system — called Vitaphone — consisted of a

motor which powered simultaneously a turntable and

a film projector (Fig. 2). Sound was projected from

behind and below the theatre screen using horns up to

14-feet in length.

Vitaphone discs were single-sided, lateral-cut, centre-

start, 12-inch and 16-inch in diameter, and played at

33 1/3 revolutions per minute. (Most of the discs were

pressed by The Victor Talking Machine Company.)

The disc was placed on the turntable at a precisely designated starting point in the run-off groove. The film

had a "start" frame at the beginning of each reel that

was set in the gate of the projector.

Discs used in the Vitaphone system were shellac,

but with less of the usual abrasive filler so that surface

noise was minimal. The disadvantage was rapid wear of

the disc; consequently, it had to be replaced frequently

in the projection room. The number of times a disc

could be played was indicated onits label and after use

— normally about 20 plays — the disc was destroyed or

returned to a local distributor. If a disc was not returned

or accounted for, a penalty was assessed. This practice

accounts, to some degree,for the rarity of Vitaphone discs.

Fig. 2: The Warner Bros. Vitaphone system consisted of a motor which powered simultaneously a turntable and a film projector.

|

|

Warner Bros. Pictures negotiated an exclusive leasing

arrangement with Bell Labs. for the Vitaphone system.

(Bell would later offer this and other systems to other

film studios.)

The first Vitaphone studio in Brooklyn, New York,

proved unsuitable for sound recording. Apart from

poor acoustics, the former Vitagraph studio adjoined

the Coney Island line of the New York transit system.

Warner Bros. leased Oscar Hammerstein's old Manhatten

Opera House for a year while the Brooklyn studio was

equipped for sound recording. Production began in

earnest at the "new" Brooklyn studio in March of 1928.

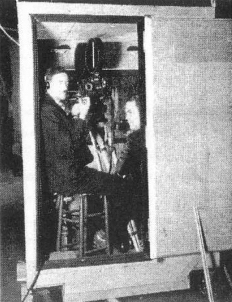

By 1929, the Vitaphone studios were operating

around the clock, 24-hours a day. Many of the earliest

Vitaphone "film shorts" were crude, single-shot productions with little on-stage action, no movement of

the camera, and the most minimal editing. Confining

the camera to a booth to eliminate the noise of its motor

was partly to blame, as this rendered it immobile (Fig. 3).

With few exceptions, Vitaphone "film shorts" were one

reel, between four and ten minutes in length.

Perhaps the most famous of the more than 400

Vitaphones produced was "The Jazz Singer" of 1927,

with Al Jolson. It was the first "talking picture" to

achieve commercial success throughout the U.S.

The Vitaphone "film shorts" offered an enthusiastic

public most every form of popular entertainment in

"talking pictures", from vaudeville to opera, dance to

theatre. Warner Bros. ceased using a disc-based sound

system in 1931. "Soundtrack" technology had advanced

and, from production and commercial points of view,

the advantages became more apparent. Warner Bros.

continued making "film shorts" at its Brooklyn studio,

using the new technology, until 1939.

The Vitaphone Project was officially established in 1991

with the purpose oflocating and cataloging Vitaphone

and other "film shorts", e.g.,

MGM, Paramount, etc., and disseminating and exchanging

information through

a network of government, commercial and special

interest groups, and private collectors throughout

North America and overseas. And towards this end,

the Project has "on-line" an international data base.

Fig. 3: The camera for Vitaphone "film shorts" was housed in a soundproof booth to eliminate the noise of its motor during production.

|

|

Public archives, commercial sound libraries and

private collections hold much of what remains of "film

shorts", some complete, others missing the film or

sound element. The Project has accessed these holdings

and from this base has built a formidable network of

contacts and resources. It continues to cast its net widely

and a critical source of information has been gathered

through interviews with performers, writers, technicians

and production people, and many others involved or

connected in some way with early "films shorts".

In its first months of activity, The Vitaphone Project

established the existence of nearly 1,500 discs. Priority is

given to finding discs needed to restore what films survive.

Support has come from some unexpected quarters.

Entertainer and film buff Jerry Lewis discovered a sound

disc of a 1929 Vitaphone in a stack of 16" transcriptions

from the popular "Martin and Lewis" show. This made

possible the restoration of "Bag O’Trix", with vaudeville

star Trixie Friganza. And Hugh Hefner is funding the

restoration of four Vitaphones — three from 1928 feature

Gus Arnheim with crooner Russ Columbo in the singer's

first screen appearances, and one from 1929 features

Green's Twentieth-Century Faydettes, the most successful

all-girl band of the early 1920s. How this restoration has

come about demonstrates the kind of partnership that

the Project has been able to facilitate: the Library of

Congress in Washington has the film and some discs,

ucta in California has the missing discs and the technical capability to undertake the physical restoration, and

private funding is underwriting the cost of the work.

Unique sound discs also found in private collections

have included a performance by Joe E. Brown from

"Don’t Be Jealous", his first "film short"; and a 12-year-

old Buddy Rich drumming, singing and dancing from

the Vitaphone "Sound Effects". The search is on for

the missing films.

A major "find" has been "Al Jolson in a Plantation

Act", the entertainer's first "talking picture" from 1926.

It offers a rare glimpse of Jolson on-stage. Both elements

of this Vitaphone were thought lost; even company

correspondence from 1933 suggested that neither could

be traced. After decades of rumour and speculation, the

discovery of the film in the Library of Congress raised

hopes, and re-kindled interest and enthusiasm in the

missing disc. Enterprise and persistence paid off with

the discovery of a badly damaged copy of the 16" disc.

It was cracked in several places and had been crudely

repaired with a household adhesive. The skill and talent

of other collectors were pressed into service and the disc

was expertly "disassembled" and "re-assembled" so that it

would track correctly and could be digitally re-recorded.

Fig. 4: Canadian contralto Jeanne Gordon (1884-1952) appeared in two Vitaphone "film shorts"

in 1927. She is shown here as Dalila in the Saint-Saens opera. (Collection: James B. McPherson)

|

|

Natural calamities have made their presence felt:

one collectors library of thousands of sound discs survived the California earthquake of 1993, but another

collection of hundreds of sound discs, nitrate film, and

an extensive library of paper material "went up in

smoke" during the disaster.

Independent of the Project's initiatives has been

the restoration and release of "Red Nichols and His Five

Pennies", filmed by Vitaphone in New York in 1929 and

featuring Eddie Condon and Pee Wee Russell, among

other great jazz artists. Collector Frank Powers discovered

the sound disc in private hands and approached the

Turner Entertainment Company, which holds the rights

to Vitaphone and many other "film shorts", and the

two elements were brought together to complete

another successful collaboration. Other commercial

reissues have included "Swing, Swing, Swing", a collection of 46 Vitaphones, and "Dawn of Sound", seven hours of a variety of "film shorts".

One Canadian singer is known to have appeared in

Vitaphone "film shorts": contralto Jeanne Gordon

(1884-1952). Gordon sang opposite two of the great

operatic tenors of the period, Beniamino Gigli and

Giovanni Martinelli. In 1927, she appeared with Gigli

in an excerpt from Verdi's Rigoletto, and with

Martinelli in excerpts from Bizet's Carmen. Production

of a third Vitaphone with soprano Mary Lewis, in

excerpts from Offenbach’s The Tales of Hoffmann, was

never completed. The American was caught up in a

dispute with Warner Bros. over her conduct "on the set".

In the Encyclopedia of Music in Canada, Jim

McPherson describes Jeanne Gordon as a "tall and

handsome woman with a magnetic personality" (Fig. 4).

Gordon made her debut at the Metropolitan Opera

in New York November 22, 1919 and remained a principal contralto with the company for nine consecutive

seasons. Appearances in European opera houses and

concert tours followed. Her last appearance was in

1930 with the Toronto Promenade Orchestra. She suffered a mental collapse soon after and was admitted to

a Missouri sanatorium where she remained until her

death of a heart attack. She was buried in her home

town of Wallaceburg, Ontario.

Gordon never quite fulfilled the promise of her early

career. Her recorded legacy includes just nine single-sided

78s for Columbia (1920-1922) and two for Victor (1927).

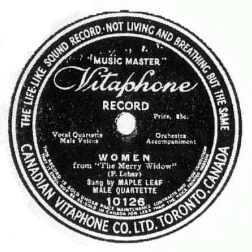

Fig. §: A Vitaphone company of Toronto record (circa 1916). "The life-like sound record — not living and breathing but the same"!

There is no connection whatsoever between this company and the Warner Bros./Vitaphone companies. (Collection: David E. Ross)

|

|

Endnotes

- The name Vitaphone was not new in 1926. The American Talking

Machine Company issued a label of the same name. The Vitaphone

label was discontinued when the company ceased operations in

1900. In 1902, there was a 7-inch American Vitaphone Record, and

between 1912-1917 the American Graphophone Company produced

a Vitaphone label for the Vitaphone Company of Plainfield, New

Jersey — the Music Master Vitaphone Record. And in 1907 a

Vitaphone Company was incorporated in New Jersey which, in

1912, introduced the Vitaphone phonograph. This company also

produced a Vitaphone label.

The Vitaphone Company of Toronto was issuing records in

1916 (Fig. 5). The masters were obtained from Columbia

— albeit of outdated material from one to five years old. The label description

states: "The Life-like sound record — Not living and breathing but

the same"!

- Kinetophone, Movietone, Phonofilm and Vitaphone were just four

of many film-sound systems. Others included the Camera-phone,

the Chronophone, the Cinephone, the Cinephonograph, the

Photocinema, the Projectophone, the Synochronoscope, and the

Vivaphone. There were many others.

Sources

- Colin J. Bray (Toronto, Ontario). Personal communication.

- Encyclopedia of Music in Canada [2nd Edition]. Toronto:

University of Toronto Press, 1992, page 538.

- David Goldenberg (Rydal,

Pennsylvania), The Vitaphone Project.

Personal communication.

- Richard Green (Ottawa, Ontario), Music

Division, National

Library of Canada. Personal communication.

- Ron Hutchinson (Piscataway,

New Jersey), The Vitaphone Project.

Personal communication.

- Guy A. Marco. Encyclopedia of Recorded Sound in the United States

(New York: Garland,

1993), pp 751-752.

- James B. McPherson

(Toronto, Ontario). Personal communication.

- William Sham. The Operatic Vitaphone Shorts.

ARSC Journal

1991;22(1):35-94.

-

Curt Wohleber. How the Movies

Learned to Talk. Invention &

Technology 1994;10(3):36-46.

What Was Seen and Heard

- Vitaphone No. 2136

[excerpt/sound

disc]: "Sing Me a Baby Song",

the Gus Arnheim Orchestra (Hollywood, 1928).

-

Vitaphone No.

? [excerpt/sound disc]: "Pals", Willie and

Eugene

Howard (New York, 1929).

-

Vitaphone Corporation demonstration film [excerpt]: "The Voice

From the Screen",

presented October 27th, 1926 to a meeting of

the New York Electrical Society.

-

Vitaphone Corporation's "Opening" Program

[excerpt]: "The

Wizard ofthe String," with Roy Smeck, and "Recitar!... Vesti la

giubba," from Leoncavallo’s / Pagliacci, performed by Giovanni

Martinelli (August 6th, 1926).

-

Vitaphone No.41s

[excerpt]: from Act III of Verdi's Rigoletto, with

Beniamino Gigli, Jeanne Gordon, Giuseppe De Luca, and Marion

Talley

(February, 1927).

-

Vitaphone No. 474 [excerpt/Golden Age of Opera LP EJS 470]:

from Act II of Bizet's

Carmen, with Giovanni Martinelli and

Jeanne Gordon (April,

1927)

|