|

Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville´s Phonautograph

by Jean-Paul Agnard

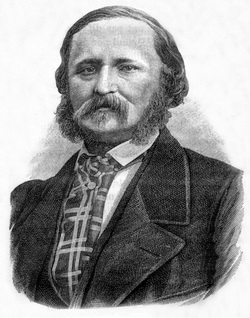

Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville

|

|

The French inventor Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville

was born in Paris on April 18, 1817.

A typographer by trade, Scott learned stenography and

became deeply interested in the possibility of recording

speech mechanically. This research led him to invent

the phonautograph, a machine capable of recording

sound vibrations visually.

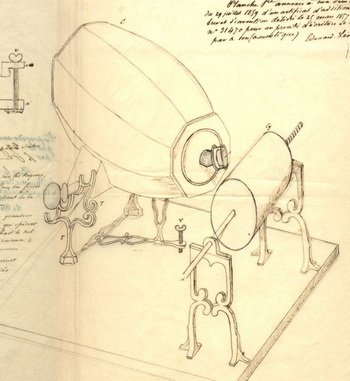

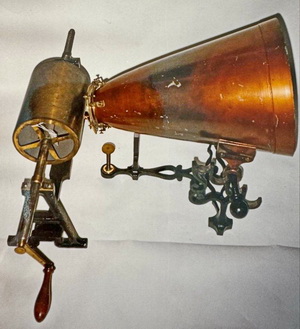

The phonautograph consists of a funnel into which one

speaks, positioned in front of a rotating drum covered

with paper blackened by smoke. At

the end of the horn

is a diaphragm that

vibrates in response

to sound. Attached

to the center of this

diaphragm is a wild

boar’s bristle, which

traces the vibrations

onto the smoked

paper. The recorded

traces are fixed by

immersing the paper

in water mixed with

egg white.

Scott patented the phonautograph on March 25,

1857—exactly 20 years before Edison’s phonograph—

under the name “speech writing by itself.”

My own third significant encounter with the phonautograph occurred in 1989 at the Musée de la Civilisation during the exhibition “From Cylinders (Edison’s) to

Laser.” For this exhibition, I loaned several artifacts

from my own institution, Le Musée Edison du Phonographe.

Scott's original 1857 patent drawing

|

|

That museum was closed in 2017 following a stroke

that left the right side of my body paralyzed. For the

1989 exhibition, the museum borrowed a phonautograph from Utrecht in Holland, as at that time no

phonautograph was known to exist in Quebec.

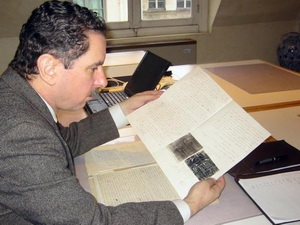

In September 1994, I wrote to Utrecht to ask for

phonautograms, as my goal was to make them speak

by one method or another. My first real contact with

the phonautograph dated back to the early 1980s,

when Allen Koenigsberg, a collector in New York and

owner of one of only four known examples at the time,

sent me a copy of Scott’s 1857 patent and its 1859

addendum. He asked me to translate these documents

into English, particularly the sections describing the

installation of the diaphragm and stylus, which I did.

The Utrecht museum replied that they regretted they

had no phonautograms. In November 1995, I wrote

again to the curator, pointing out that

their Phonographic Bulletin of April 1977 mentioned

phonautograms in its references. I received no reply. In

July 1997, using the Internet, I sent an email containing the text of my unanswered letter.

The curator replied that he had since changed positions within the university, explaining why the letter had

probably been lost. Once again, the answer was: no

phonautograms.

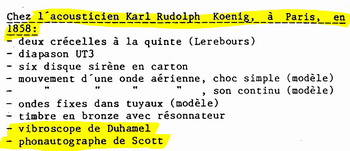

Catalogue record, Musée de la Civilisation, Quebec City

|

|

That same summer of 1997, while visiting the reserves

of the Musée de la Civilisation with Mme Toupin, I

made an unexpected discovery: a “Duhamel vibroscope,” corresponding to the rear section and drum of

a phonautograph. A few minutes later, we also located

the metallic horn, shaped as a paraboloid of revolution,

though still lacking the recording head. By consulting

the list of scientific instruments purchased in Paris in

1858 by Abbé Hamel for Laval University, we were able

to identify the

origin of this

instrument.

I had originally gone to the

reserves

searching for

a curious

hand-driven

Berliner

gramophone

that I had

seen in the

1970s at

the Petit Séminaire in Quebec, and again in the early 1980s at the

seminary’s museum.

Correspondence with Teylers Museum, Haarlem, Holland

|

|

In September 1997, I contacted the Utrecht curator

once more, asking if he might lend me the recording

head so I could make a copy. He refused, but promised

to send sketches. He also informed me that the Teylers

Museum in Haarlem, Holland, possessed a phonautograph.

I immediately wrote to request a loan. In October, they

declined but promised to provide information.

On September 26, I wrote to the Musée de la Civilisation to explain my project of making phonautograms

audible. To do this, I needed access to a complete

phonautograph, which I had been unable to locate

elsewhere despite years of effort. I emphasized that

this would be a world premiere and could not go unnoticed.

David Giovannoni

|

|

In April 1998, I again wrote to Mme Toupin requesting

a loan of their phonautograph so I could make a complete copy. I received no response.

In November 2000, Mme Toupin and I returned to the

reserves to continue our search for the missing recording head. Our plan was simple: I began from the location where I had found the vibroscope, and she started

from where the horn had been discovered. As we

opened boxes and

drawers and gradually closed the distance between us,

she finally found

the recording head.

That same month, I submitted a new request—this time

for a long-term loan of the phonautograph for my museum in Sainte-Anne-de-Beaupré. This request was

accepted in December, and in January 2001 the

phonautograph arrived in Sainte-Anne. After seven

years of continuous effort, I was finally able to produce

phonautograms, having been unable to locate any original examples.

Original phonautograph

|

|

Between 2001 and 2007, I produced several phonautograms. During this period, I contacted a university

professor in the United States—the same individual

David Giovannoni later contacted in 2008 to make the

famous 1860 phonautogram “Au clair de la

lune” audible, now accessible online through Wikipedia.

Unfortunately, because I was unable to properly fix the

smoked paper and because the professor refused to

work with photocopies, I had to abandon the project—

though I was, quite

literally, only a wild

boar’s hair away

from success.

In 2008, David Giovannoni traveled to

Paris with a high-

precision scanner

to digitize original

phonautograms. That same year, I

began building my

first phonautograph.

Unable to reproduce

the version with the

metal paraboloid horn, I

instead chose to replicate the model shown

in Scott’s patent, featuring a wooden ellipsoidal horn. In April, I experienced what I call

my “chemin de Damas”—a sudden understanding of

how lateral recording on paper was possible even

though the diaphragm vibrated perpendicularly to it. I

was driving back from Wayne, New Jersey, still reflecting on the problem, when the solution became clear:

the diaphragm is not parallel to the axis of the drum,

but set at a slight angle.

The timing was ideal. I delivered my first machine to

Mr. Eric von Grimmenstein, president of the Dictaphone Museum in Indianapolis, Indiana. In October

2014, I delivered my second machine to David Giovannoni.

|

|

Construction of the octagonal horn

|

|

In early 2016, I began work on a third machine

for the Phono Museum in Paris, to commemorate the

200th anniversary of Léon Scott de Martinville’s birth

on April 25, 1817.

On that occasion, Scott’s grandson, Laurent, was present, and I had the opportunity to speak with him. He

told me that a phonautograph had once been kept in

his family’s holiday home but had been stolen. He

could not say which type it was. It was almost certainly

a model with a metal horn, as no original wooden-horn

phonautograph like the ones I build has ever been

found. However, it may also have been an experimental version previously undocumented.

The machine itself is large, mounted on a wooden base

measuring 22 by 31.5 inches. To fabricate the octagonal-profile horn, the first step is to create eight curved

“petals.” These are made from special bendable mahogany planks, each consisting of two layers glued together with contact cement on a custom mold. Once

removed, they permanently retain their shape.

The eight petals are then arranged in order to preserve

the orientation of their surfaces. Each petal is cut so

they can be joined two by two, with their edges cut at

an angle of 67.5 degrees, and then assembled four by

four.

At this stage, the horn exists in two halves. Before joining them, plaster of Paris is applied to form an ellipsoid

of revolution. To achieve this, I built a special rotating

device that allows the plaster to be shaped while still

wet. I use a prepared spackling material that appears

pink when wet and turns white when dry.

All metal parts were already available, as I had manufactured them in 2008 in anticipation of building four

possible machines. The components supporting the

horn and the drum were copied directly from the original parts of the Quebec phonautograph and laser-cut

from a metal plate one centimeter thick.

The phonautograph reminds us that the recording of

sound began not with playback, but with the desire to

make the voice visible and permanent. My own work

with this instrument reflects that same curiosity and

perseverance. Through reconstruction and experimentation, the phonautograph continues to speak—not by

sound alone, but through the traces it leaves

behind.

Replica of Scott's Phonautograph built in 2014 by Jean-Paul Agnard

|

|

|