|

Pioneers in the Evolution of Electrical Sound Recording:

The Guest-Merriman Electrical Recording System, 1918-1922

© Trayce Arssow

(of the Yugoslav Discographic Society)

Fig 1. Guest (right) and Merriman (left)

experimenting, c.1918-1919

|

|

It has been an established canon,

practically a dogma, that the history

of electrical recording begins in

1925, with the system developed by

Western Electric in North America.

While the Western Electric system

would prove to become the best

available recording method at the

time, by no means was its concept

the first of this kind. Prior to the Bell

Laboratories research, several attempts had been made to develop an

electrical recording process that involved microphones and electrical

disc cutting, which was to replace the

acoustic or mechanical horn recording technique used since Edison invented it, involving no electricity or

amplification.

As a matter of fact, the earliest example of electrical recording of any description was the pioneering work of

Lionel Guest and Horace Merriman in Great Britain,

invented five whole years before the Western Electric

system was offered to Victor and Columbia.

Major Lionel Guest (1880-1935) was a British aristocrat educated at Eton and Cambridge, who joined the

British army during the Great War, for which services

he was awarded the Military class of O.B.E., while Canadian Captain Horace Merriman (1888-1972) was a

B.A.Sc. graduate in Electrical Engineering and later

demonstrator at the University of Toronto before he

served with the Royal Air Force during the Great War.

Although Guest and Merriman might have met already

before the war, while Guest was engaged on financial

business in Canada, as aide to the Canadian governor-

general, it was much more probable that these two got

to know one another while they both served in kindred

branches of the imperial military forces during the war,

Guest in the Royal Flying Corps and Merriman in the

Royal Naval Air Force.

Guest, who was a stock broker professionally, had a

passion for astronomy but he had a versatile mind,

and inventions of an engineering character always had

an attraction for him. After the war, he worked in conjunction with Merriman, who was an electrical engineer, a cooperation that would result in their being coinventors of the very first electrical recording device

ever made. [Fig 1] They must have been conducting

their experimental electrical sound recordings not later

than the autumn of 1918, because already in January

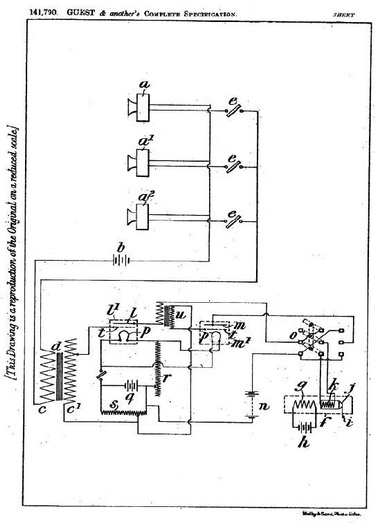

1919 they applied for an ‘Improved Means for Recording Sound’ patent, which amongst the rest states: ‘[...]

instead of placing the sound producer in direct proximity to the recording device, as has heretofore been the

custom, we provide for the recording taking place at a

distance from the sound producer.’ The complete specification was submitted within six months, in July 1919,

in which inter alia it is stated: ‘Now, we have ascertained by experiment that excellent results are provided by the employment of a recording appliance of the

kind described in the Specification of Patent

No.18,765 of 1913’ (which essentially meant that they

made use of a vibration motor). [Fig 2]

Fig 2. ‘Improved Means for Recording Sound’

patent sketch, 1919

|

|

It was not until the following year, however, that they

developed a complete electrical recording system. In

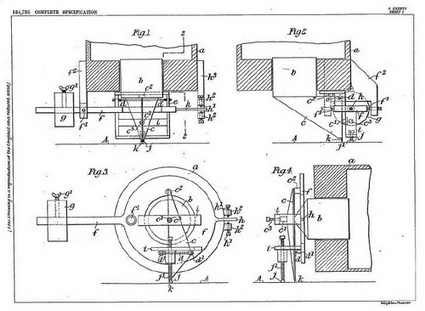

February 1920 they applied for an ‘Improvements in

Sound-Recording Apparatus’ patent, which states: ‘This

invention relates to sound-recording apparatus and

has for its object to provide improved means for

mounting the recording stylus and connecting it to the

source of vibration so that it “floats” and follows the

slight rise and fall of the moving wax surface on which

the record is made.’ The complete specification was

submitted in early November 1920, only a few days

before the invention was ever to be put in practice on a

larger scale. Like patents in general, the contents of

the specification is extremely technical in nature, which

makes it very difficult to summarise it, except perhaps

by quoting from its introductory part: ‘This invention

relates to sound-recording apparatus of the kind in

which the recording stylus-bar is pivoted to a floating

beam, which is itself pivoted to a stationary member of

the device in such a manner that the stylus-bar floats

and follows the slight rise and fall of the moving wax

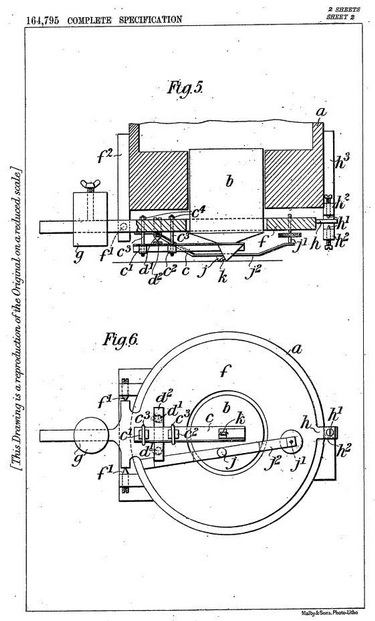

surface on which the record is made.’ [Fig 3-4]

The actual particulars of the Guest-Merriman recording

method can be much better understood on the basis of

the one and only known commercial recording session

that had ever been carried out with their invention, rather than on the basis of the technical language used

in their patents granted. On 11 November 1920,

amidst the nationalistic frenzy in France and Britain

upon the commemoration of the second anniversary of

the armistice, ceremonial burials of the Unknown Soldier/Warrior were simultaneously held in both Paris

(Arc de Triomphe) and London (Westminster Abbey). It

was upon this occasion, at the funeral ceremony of the

British Unknown Warrior in Westminster Abbey, that

the Guest-Merriman electrical recording system was

first demonstrated and put to practical use, which produced the earliest electrical recordings ever to be commercially issued anywhere in the world.

The ceremony was carried out in the presence of the

monarch, emphasising that it was a prime state occasion, taking place right after the unveiling of the Cenotaph a quarter of a mile away in Whitehall an hour earlier (the two ceremonies were understood as belonging

together). Both in composition and in scope, it anticipates all subsequent state and royal funeral ceremonies which would take place at the same venue in the

next hundred years. Before turning to the particulars of

how Guest-Merriman’s pioneering undertaking was

done at all, it may not be inopportune to skim through

the order of service which was part of the ceremony

and thus the subject of their historic recordings. The

order of service deserves a detailed analysis from musicological, textual, theological, ideological, and other

points of view, which at this point shall not be attempted, but instead a short summary is being offered with

the view to providing an idea about its content and extent, before proceeding to the actual recording system.

Beginning at 10 a.m., H.M. Grenadier Guards Band,

under the direction of Capt Albert Williams, Mus.Doc.,

played Arthur Sullivan’s ‘In Memoriam’ Overture, Félix-Alexandre Guilmant’s ‘Marche Funèbre et Chant

Séraphique’, then César Franck’s Morceau Symphonique ‘Rédemption’, and Arthur Somervell’s ‘Killed

in action’, the slow movement from his Thalassa symphony. At 10.45 a.m., the Choir and Clergy, headed by

the Beadle and the Cross of Westminster, moved from

the Nave to the High Altar, singing ‘The Supreme Sacrifice’ hymn. The Congregation was asked to join in singing the hymn ‘O God, Our Help in Ages Past’, and then

the Congregation knelt as the Precentor said the prayer ‘Our Father’.

Fig. 3. ‘Improvements in Sound-recording Apparatus’

patent sketch, 1920

|

|

At 11 o’clock silence was kept for the space of two

minutes, not just at the Cathedral but throughout London which came at a standstill (it was a busy Thursday), at which point the Cenotaph was being unveiled

by the King a mile away in Whitehall. The Russian

‘Contakion of the Faithful Departed’ was then sung,

after which the Dean said several Collects with all devoutly kneeling. Then the Congregation stood while the

Choir moved in procession to the North Porch, singing

the hymn ‘Brief Life Is Here Our Portion’. By this point

the casket with the Unknown Warrior was being

brought into the cathedral. Then, in procession from

the North Porch to the Grave side in the centre of the

Nave, ‘The Order for the Burial of the Dead’ was sung;

the seven funeral sentences, verses from various

books of the Bible, were taken from the Anglican Book

of Common Prayer, for six of which the music was newly composed by William Croft, whereas only the last

sentence retained the original composition by Henry

Purcell.

From about noon onwards, first the ‘Equale for Trombones’ by Ludwig van Beethoven was performed. Then

the 23rd psalm ‘Dominus Regit Me’ was sung, followed

by ‘The Lesson’ from Revelation 7: 9-10, and the hymn

‘Lead, Kindly Light’. Then, while the earth from the soil

of France was being cast upon the body of the Unknown Warrior, the Dean said the ‘Committals for Believers’, selections from the Book of Common Prayer

pertaining to Burial, followed by a verse from Revelation 14: 13, before the Precentor said ‘Our Father’

once again. Then the hymn ‘Abide With Me’ was sung,

after which came one more Collect from the Book of

Common Prayer, followed by one more other prayer.

Finally, Rudyard Kipling’s poem ‘Recessional’ was sung

by all standing, and after the ‘Blessing’ and the

‘Réveille’ was performed (the latter as a reference to

resurrection), G. J. Miller’s ‘Grand Solemn March’ was

played as the King was leaving the church.

As it is evident from the order of service, the ceremony

lasted for about three hours, and to a large extent consisted of elements from the Anglican liturgy pertaining

to burial. The service was only very loosely built around

the Prayer Book funeral service, but at least included

all of the Funeral Sentences, with the first six sung in

the procession from the North Porch to the centre of

the Nave and the last one after the Committal. At any

rate, the entire ceremony was distinctly Anglican in

content. The musical component on the other hand, in

addition to Anglican hymns and several English composers with appropriate war-related themes, also included works by a couple of composers from allied

France, as well as one piece originating from imperial

Russia. The inclusion of Beethoven in the programme

probably had the significance of referencing defeated

Germany. A few years later the ceremony would have

surely been broadcast on the radio, and decades later

on television. However, in the period in which it actually

occurred the only possible means at least for an audio

presentation of such a ceremony to the wider audiences was by having it recorded all the way through, so

somehow Guest and Merriman had

been given special permission for

such an undertaking. British motion

picture companies filmed the

transport of the coffin from France,

then the parade associated with the

unveiling of the Cenotaph, and the

rituals outside the cathedral, but apparently none of them was allowed to

film the ceremony within the cathedral itself, although some still photos

do exist. Apart from the historical importance of the occasion itself, the

Guest and Merriman recording enterprise was of immense importance

from the perspective of history of recorded sound. So let us now turn to

the obvious question of how it was

done.

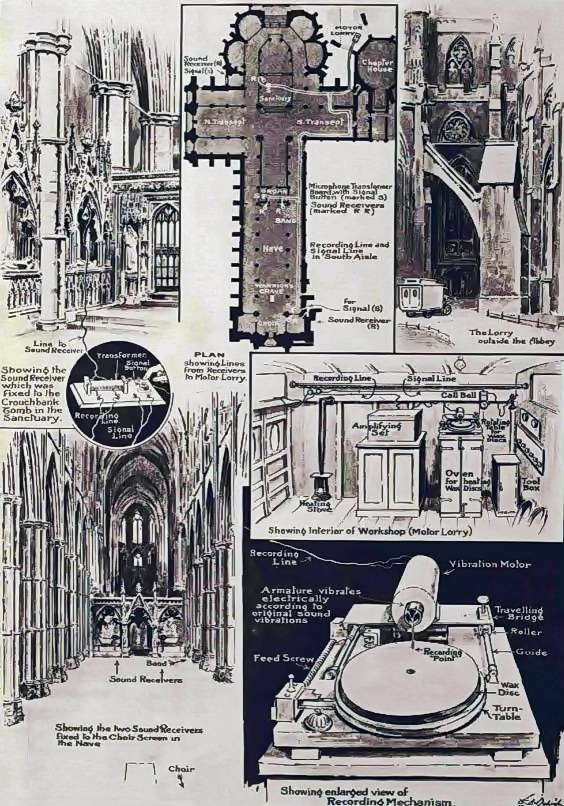

With the view to introducing the new

system to the wider audience of laymen who did not necessarily read patent digests, the Guest-Merriman experimental electrical

recording process was explained in detail in a diagram

published in the Illustrated London News, drawn by their

artist W.B. Robinson from material supplied by Guest

and Merriman themselves, as well as in the brief descriptive paragraph ‘How music at the Abbey burial of

the Unknown Warrior was recorded in a lorry outside the

building: a new electrical process.’ [Fig 5] In a nutshell,

cutting the wax masters was made by using four carbon

microphones placed at four different locations inside

Westminster Abbey, and connected with cables running

to the recording apparatus (a valve amplifier and a moving coil cutting head), stationed in a remote motor lorry

parked in the street outside the eastern end of the Abbey (containing a workshop with the recording mechanism where Guest and Merriman sat amidst heating ovens and cutting lathes). Now let us deconstruct this diagram and go through its components.

Fig 4. ‘Improvements in Sound-recording Apparatus’

patent sketch, 1920

|

|

The recording machine was connected by wires with four

sound receivers (SR) placed at different points; these

were essentially telephone microphones with small

horns attached, or rather they came at the narrowest

part of the horn where otherwise a diaphragm was

placed, as can be noticed by taking a very close look at

the diagram. This evidences that acoustic horn recording

was a strongly established fact, and even when carbon

microphones were introduced they were meant to replace the diaphragm but not to eliminate the horn, at

least in these pioneering electrical recordings. Considering the colossal size of the ‘studio’, each of the four microphones was meant to record a different segment of

the ceremony pending on the place as to where every

‘artist’ performed. At each of the points was posted a

signaller who, by pressing a signal button (SB) on a microphone transformer-board, signalled to the operators

in the lorry when to begin and cease recording with that

microphone. The location of the four microphones and

the respective ‘artists’ was as follows:

SR1 & SB1, near Warrior’s grave in South Aisle:

Westminster Abbey Choir;

SR2 & SB2, in the middle of the Nave: Organ

played by Sydney Nicholson;

SR3 & SB3, in the middle of the Nave: H.M. Grenadier Guards Band;

SR4 & SB4, at Crouchback Tomb in the Sanctuary:

presumably the clergy.

The two sound receivers SR2 & SR3 were fixed to the

choir screen in the nave, with Sydney Nicholson at the

Organ on the left-hand side and HM Grenadier Guards

Band on the right-hand side. The fourth sound receiver

SR4 was fixed to the Crouchback Tomb in the sanctuary,

with the recording line connecting it to the microphone

transformer board (line from sound receiver, transformer, signal line, recording line, signal button).

The historic recordings of the ceremony honouring the

Unknown Soldier at the Westminster Abbey were not only the very first electrical recordings ever made that were

meant to be released commercially, but also they were

the first ‘long distance’ recordings of any kind, all previous acoustic recordings being executed at very close

proximity between the artist, horn and the cutting lathe.

Thanks to their ingenious invention recording now could

be done on location, so by using electric cables the

Guest-Merriman system was able to detach the microphone from the recording machine by a distance of dozens of meters, and miles if necessary, which was something totally unprecedented.

The interior of the motor lorry workshop comprised recording line, signal line, call bell, heating stove, amplifying set, rotating table for wax discs, oven for heating

wax discs, and tool box. This consisted of the usual

gramophone turn-table with a revolving wax disc, but,

instead of a recording diaphragm operated by sound, it

had an electrical device for engraving the wax, which

has also never happened before in sound recording.

The recording mechanism comprised recording line,

recording point, wax disc, turn table, feed screw, travelling bridge, roller, guide, and vibration motor (armature

vibrates electrically according to original sound vibrations – this was the only external component of the

Guest-Merriman system which they credited to Patent

No.18,765 of 1913).

During the elaborate three-hour service, a total of 36

masters on 12” wax plates were cut in the lorry, each

lasting for about 4:30 minutes. This indicates that

Guest and Merriman recorded the entire ceremony

from start to finish with every single audio component

of it, may it be musical or spoken or a combination of

the two. Had it all been successful, these recordings

would have resulted in a triple album consisting of 18

records with cumulative duration of nearly three hours!

The outcome was far from satisfactory, however. From

the numerous numbers recorded during the ceremony

only two (i.e. 5.5%) were considered suitable for issue,

but even that is debatable. Or rather, the best two had

to make it to the final cut in order to get at least one

double-faced record, otherwise the entire enterprise

would have been totally in vain. Apparently, both these

quasi successful recordings were made towards the

very end of the recording session, indicating that during the first couple of hours of the ceremony Guest and

Merriman had considerable difficulty in capturing the

sound.

Of two recordings deemed satisfactory one was the

hymn ‘Abide With Me’, written by Scottish Anglican cleric Henry Francis Lyte in 1847 just before he died, and

it is most often sung to the tune ‘Eventide’ composed

by the English organist William Henry Monk in 1861.

The other recording that was deemed satisfactory was

Rudyard Kipling’s poem ‘Recessional’ written in 1897

on the occasion of Queen Victoria’s diamond jubilee. It

was sung by all standing, meaning that the poem was

not only recited but also there was an accompanying

music to which the congregation sang. It seems that on

this particular occasion the tune used was ‘Melita’ by

J.B. Dykes, a prominent Victorian clergyman and compiler of hymn tunes. Both works were performed by the

Westminster Abbey Choir directed by Sir Sydney Nicholson, Westminster Abbey Organist and Master of the

Choristers since the previous year, the Congregation,

and H.M. Grenadier Guards Band.

Fig 5. Diagram of the Westminster recordings,

The Illustrated London News, 18.12.1920

|

|

The double-sided record resulting from the earliest

Guest-Merriman produced electrical recording ever to

be made was pressed later in November 1920 by the

British Columbia Graphophone Co., whose involvement

possibly went much deeper than it is generally realised,

and it might have been instigated by its forward thinking general manager, Louis Sterling. The centre label

on the disc itself reads: ‘Memorial Record made at

Westminster Abbey on 11 November 1920 at the funeral ceremony of the burial of the Unknown Soldier by

Guest & Merriman electrical process. Published for the

Westminster Abbey Fund by Columbia Graphophone

Co. Ltd.’ [Fig 6] The record was issued in 1000 copies

(rather than 500 copies each of two single-sided records, as it might be construed from a line in the Illustrated London News), which retailed at 7½ shillings,

with all profits going to the Westminster Abbey Restoration Fund appeal, and orders were to be sent to the

Precentor, Little Cloisters, Westminster. This implies

that the Abbey was granted sales rights practically of

the entire stock of the record, which is probably why

the special permission to record the whole ceremony

had been given in the first place. Released in December 1920, and coinciding with the festive season, the

total proceeds from the sales of the record would have

amounted to £375 (which was worth about £20,000 in

today’s money value). If all the copies were sold by the

end of that month, it might very well be the case that

this record was British Christmas No.1 for that year

(the first or one of the earliest in this category), although additional research will be needed in order to

find out how the record faired upon its release.

The sound quality of the Guest-Merriman system was

not satisfactory, however. The weak link in the recording system was the carbon microphone, which was little more than a telephone mouthpiece. Yet, the bigger

drawback might have been the recording head based

on the ‘Fessenden Oscillator’, designed as a sonar

transducer by Canadian inventor Reginald Fessenden.

The significantly poorer sound quality of these electric

recordings makes it difficult to differentiate between

instruments and singing, so much so that it is hard to

discern if only instruments are playing or if there is also

singing. It seems as though the sound coming from

H.M. Grenadier Guards Band is captured the best, but

each of the two released works sound quite like the

earliest acoustically recorded cylinders. Even though

the new technique revealed bass and treble sounds

hitherto unheard on recordings, the end result of these

earliest electric recordings proved so less satisfying

than the regular acoustically recorded records available at the time, except perhaps that it would have been

difficult for the acoustic horn to capture such a large

group of people (Organ, Choir, Congregation, Band).

Although the Westminster recordings were of abysmal

technical quality, British Columbia officials were sufficiently intrigued to invite Guest and Merriman to undertake experimental recording sessions in their London

studio. However, the process was soon judged unsuitable for Columbia’s use, as acoustic recordings of the period produced far superior results, so after evaluation

British Columbia decided not to adopt the Guest-

Merriman system for continual usage, and the relationship was terminated. The disappointing outcome in Britain triggered Guest and Merriman to acquire patents of

their invention in France and Germany, for which purpose applications were made practically simultaneously

in both countries in February 1921; a French patent was

granted in October 1921, whereas a German patent was

granted in August 1922 (both of them are identical to

the text of their British patent complete specification of

November 1920), but apparently success was found in

neither country.

Failure to propel their invention in Europe was the reason why, in October 1921, Guest and Merriman went to

North America to try to persuade recording companies

there to adopt their electrical recording system, but they

were met with a similar lame reaction. In late October

1921, experimental electrical recording sessions were

made in American Columbia’s New York studio, during

which Gladys Rice recorded ‘The Rosary’ four times electrically and once acoustically accompanied by various

pianists. The masters were shipped to Bridgeport in early

November 1921, but none was approved for release,

and the American Columbia electrical tests appear to

have been quickly discontinued. Thus, the Guest-

Merriman system was rejected once again, first by British Columbia, and this time by Columbia’s American

branch. Confronted with these melancholy circumstances, by 1922, after over three years of experiments and

four patents granted, Guest and Merriman were forced

to abandon their plans seemingly for good, so their system was not further developed, at least not with the Anglo-Canadian partnership in the driving seat. Yet, a year

later their system possibly resurfaced once again on the

recording scene, also unsuccessfully, and this time once

and for all: in 1923 American jazz orchestra bandleader

Paul Whiteman invested heavily in the electrical recording process of an unnamed British inventor hoping to

license it to Victor, but he was rebuffed by that company’s executives – might this British inventor perhaps

have been Lionel Guest?

Fig 6. Central labels of Memorial Record,

containing the Westminster recordings, 1920

|

|

The commercial release of an electrical recording in late

1920, however limited in scope and quality, demonstrated that a major record company such as British Columbia was taking the matter of electrical recordings seriously, even though the technology obviously was not

ready yet for full-scale commercialisation. As a matter of

fact, British Columbia took advantage of its privileged

position in the Guest-Merriman experiment, and in the

following few years, after breaking up with the two inventors, it continued its researches with electrical recordings behind closed doors in secrecy with other researchers. While playback still remained on acoustic machines

sound quality was secondary, even if it might have been

recorded electrically, so it is believed that British Columbia actually produced several such records during 1922-

1925 – and so did Orlando Marsh on his Autograph Records, before everyone was eventually outplayed by

Western Electric.

The dogma that electrical recordings began in 1925 still remains. If we consider the quality of sound recording that

it brought along with it, then certainly it deserves the credit of being a milestone in the history of recorded sound,

even revolutionary. Yet, no revolution appears ex nihilo, and there are always many important forerunners who

pave the way towards it. In this respect, the achievement of two visionaries, Lionel Guest and Horace Merriman, is

extraordinary, as their work helped usher in the electrical era of recording.

Their effort may not have produced the best sounding record the world has ever heard, but their sound recording

concept was a historic push forward in the evolution of sound recording. The system which they developed had

clearly been used as the blueprint in all subsequent similar developments, and it is in the core of the concept of

electrical recording such as we know it. It marked a key milestone in recording history and the pursuit of hi-fidelity

sound, and therefore Guest and Merriman deserve full credit for their contribution to the history of recorded sound,

much more than a passing reference or a paragraph at best. It is for this reason that this paper sought to research

their accomplishment, and albeit slightly belatedly to pay homage to their genius upon the centenary of electrical

recording, which as we ought to realise was not a revolution that occurred overnight but a long process of evolution

lasting for nearly a decade, in which the Guest-Merriman system occupies a prominent place.

Bibliography

- Colin Brownlee, ‘Experiments in Electrical Recordings’, Archive of Recorded Church Music, https://

recordedchurchmusic.org/electrical-78-s-1926-1957.

- Nick Dellow, ‘A Revolution in Sound: The Development of Electrical Recordings and the Introduction of the

Western Electric System,’ CLPGS Lecture, 2023, 25pp.

- The Funeral Service of a British Warrior on the Second Anniversary of the Signing of the Armistice, 11 November 1920, 12pp.

- Lionel Guest and Horace Merriman, ‘Improved Means for Recording Sound’, British Patent Office #141,790,

applied 18.01.1919, accepted 19.04.1920.

- Lionel Guest and Horace Merriman, ‘Improvements in Sound-recording Apparatus’, British Patent Office

#164,795, applied 10.02.1921, accepted 10.06.1921.

- Lionel Guest et Horace Merriman, ‘Perfectionnements aux appareils d’enregistrement du son’, Office National

de la Propriété Industrielle, Brevet d’Invention No.530.594, applied 07.02.1921, accepted 06.10.1921.

- Lionel Guest und Horace Merriman, ‘Apparat zum Aufzeichnen von Tönen’, Reichspatentamt, Patentschrift

Nr.357316, applied 28.01.1921, accepted 22.08.1922.

- ‘“Long Distance” Gramophone Records in the Abbey’, The Illustrated London News, Vol. CLVII No.4261, Saturday 18 December 1920, 14.

- Library and Archives Canada, RG138 - 80939, R1223-50-0-E: Electrical recording by Guest-Merriman process

at Services of the Unknown Soldier, 11.11.1920.

- ‘Horace Merriman: A Radio Pioneer’ (article from 1954) https://radiocom.ca/x_MerrimanHorace.htm

- Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Vol.96, London, February 1936, 292-294.

- Matthias Range, British Royal and State Funerals: Music and Ceremonial Since Elizabeth I, Woodbridge, Suffolk, Boydell Press, 2016, 289-291.

- Allan R. Sutton, Recording the ‘Twenties: The Evolution of the American Recording Industry, 1920-29, Denver,

CO, Mainspring Press, 2008, Ch.15: Dawn of the electrical era (1920-25).

- Liz Tuddenham, ‘Electric Columbias 1922-1925, Where Are They?’, CLPGS For the Record 86, Summer 2023,

4-12.

- Paul Whiteman, Music for the Millions, ed. David A. Stein, New York, Hermitage Press, 1948, 5-7.

Trayce Arssow, of the Yugoslav Discographic Society, holds an MA in History with expertise in Central, Eastern, and

South-Eastern Europe. In the past several years they discovered scholarly interest in discography, history of the

sound recording industry, record companies’ business history, history of technology and science, musicology and

ethnomusicology. Driven by their multi-disciplinary interests, at present they are pursuing a book-length project on

pioneering British-Canadian sound recording engineer and inventor Paul Voigt, entitled ‘Paul Voigt’s Quadrangular

Record: Edison Bell’s Early Electrical Recordings in Great Britain and Eastern Europe, 1925-1933.’ The

author wishes to acknowledge the support in their researches of the Richard Taylor Bursary by the City of

London Phonograph and Gramophone Society (CLPGS).

|