|

Novelty Piano Ragtime: Where it Came From, Where it Went

by Matthew de Lacey Davidson

Matthew Davidson is a pianist and composer currently resident in Nova Scotia, Canada

|

|

“Novelty Piano Music” is a sub-genre of ragtime music.

It slowly started to develop in the late 1910s, but

reached its zenith in the 1920s.

All cultural phenomena must be examined within a historical context. We can’t understand Elvis Presley’s

early career by starting at the point in time where Ed

Sullivan’s producers censored his hip-twitching on U.S.

national television. We cannot know about Laurel and

Hardy by first discussing the end of the short film, Our

Wife, where a cross-eyed justice of the peace (played

by Ben Turpin) asks to kiss the bride and then accidentally kisses Stan Laurel. Similarly, Novelty piano

ragtime must also be understood within a historical,

social, and economic context.

As to the origins of ragtime, too much is often left to

speculation. What can be said with certainty is that it

originated sometime before the 1890s, most likely in

the United States. One can find some elements of ragtime (such as the “boom-chick” march-like pattern in

the left hand, and untied syncopation) in early published U.S. piano works which cruelly parody black people in America (such as Thomas Hindley’s Patrol

Comique, published by New York Publishing Company

in 1886) (1).

Origins of Novelty Piano Ragtime

Ragtime pianist Eubie Blake (1887 – 1983) said in

interview that he didn’t know where it came from, but

that he had heard it all his life (2). And when ragtime

eventually became a published form of music, it was,

most often, greatly simplified. As Blake said to pianist,

composer, and historian, Max Morath, it had to be arranged for the “girls in the five and ten-cent store.”

Parenthetically, the five and ten-cent stores (3) were

where you could buy popular sheet music, and a young

girl would demonstrate it for a customer on the piano.

Contrary to modern belief, during early ragtime’s initial

prominence, the general public associated the music

with songs – vocal music – and with military bands (4),

in addition to guitars, mandolins, and banjo (5). As a

syncopated piano style, it was also associated with

dancing (6).

The book, Rags and Ragtime, creates a division of seven major styles of ragtime (7). In my opinion, having

played and listened to this music for over 45 years, I

can see the usefulness in these sub-categories, even

though I sometimes question the apparent arbitrariness of some of the dates (e.g. they state that Novelty

Piano Ragtime stops at 1928, however, there are a

number of composers, such as “Zez” Confrey and Arthur Schutt, who both wrote and/or performed Novelty

rags in the 1930s).

Jasen & Tichenor call the first manifestation of ragtime,

which is less sophisticated than many of the later

styles and shows influence of folk music, as “Early Ragtime” (8). An example of this style is Buffalo Rag by

Tom Turpin, the first black American to publish a piano rag, as performed by Fred Van Eps, the leading banjoist

of his day, in 1905. Vess L. Ossman played in 1906. (9)

The next style is what Jasen & Tichenor called, “The

Joplin Tradition,” and what Harriet Janis and Rudi

Blesh called “Classic Ragtime” in the first book documenting the history of this music, They All Played Ragtime (10). An overly-simplistic explanation might be,

“the piano rag music of Scott Joplin and those directly

influenced by him” (e.g. Joseph Lamb and James

Scott). An example of this style is the rag, Heliotrope

Bouquet (1907), a collaborative rag by Louis Chauvin

(who composed the first two sections) and Scott Joplin

(who wrote the rest) (11).

Immediate Precursors

The next two styles are closely inter-related, and both

had a huge bearing on the Novelty Piano Ragtime style.

The first, “Popular Ragtime,” (12) is where the forces of

Tin-Pan-Alley (popular music) publishing companies

realized that serious money was to be made from this

new fad . Surprisingly, there were some composers

who achieved a fair degree of artistry in this style, the

most famous of whom was George Botsford, who wrote

Black and White Rag (1911). This work popularized a

pattern of rhythmic note-group asymmetry to emulate

the syncopation (where the stress falls on the weaker

beats of the bar) of earlier ragtime. For example:

The top numbers represent the

right hand, the bottom – the left.

The marker (|) represents where

the bar line is to separate the

“boom-chick, boom-chick” (note-

chord, note-chord) march-pattern

in the bass. As you can see, the

fast three note patterns over the

slower 1 & 2 & pattern in the left

hand eventually come together

after one and a half bars. It is important to remember this, because we’ll see it again in Novelty

Ragtime, only disguised.

A more interesting musical example, however, and one which uses

the same device is a recording of

Botsford’s Grizzly Bear Rag, recorded by the Imperial Symphony

Orchestra on Pathé around 1910

(13).

What Jasen & Tichenor refer to as

“Advanced Ragtime,” is actually similar to Popular Ragtime, but technically more challenging for pianists to

play. One of the exponents of this style, Charley

Straight, was, in my opinion, more important in terms

of his work in the field of piano roll arrangement. He

hired Roy Bargy, an exponent of the Novelty Ragtime

style, a move which launched Bargy’s career as a pianist, bandleader, and arranger. Hot House Rag

(1914), the work of Paul Pratt, (14) another Advanced

Ragtime composer (but who was published by Scott

Joplin’s publisher, John Stark), begins to show the pianism and rhythmic techniques which became some of

the hallmarks of the Novelty Ragtime style.

Another technique we see during the later teens is the

constant use of triplets (in short, groups of three notes,

1-2-3, 1-2-3, 1-2-3, played very quickly), and one of the

first ragtime-related works to use this technique was

Felix Arndt’s work, Nola (published by Arndt in 1915,

and Sam Fox Publishing in 1916). Although some

might argue that “this is not ragtime,” this use of triplets will also become prevalent in many “Novelty Rags

(15).”

Social and Economic History Behind the Music

We are now in the mid to late teens of the twentieth

century. At this point, I think it appropriate to discuss

what was socially and economically going on in North

America in general, and the United States in particular.

Although Novelty Piano Ragtime most likely emerged

before the 1920s, it has become

forever associated with what many

people call the “roaring twenties.”

In the interests of not seeing the

past through “rose-tinted glasses”,

however, it’s important to

acknowledge that the 1920s were

actually “roaring” for only a very

select minority.

According to John Kenneth Galbraith in The Great Crash, 1929,

(16) the majority of wealth in the

United States leading up to 1929

was centered in the top five percent of the U.S. population

(Galbraith argues that this was one

of the five major weaknesses which

lead to the crash and the Great Depression, along with foreign trade

imbalances, i.e. during WWI the

U.S. became a creditor nation, exporting more than it imported).

Most black people, in particular, lived extremely difficult lives during the 1920s. Many in the U.S. lived in

the South, were sharecroppers, and lived in extreme

poverty. A great many immigrants to the U.S. suffered

a very high rate of unemployment throughout the

1920s, did not have much education, and had to work

for very low wages, enduring much discrimination in

the process. In addition, farmers, people living in rural

areas, coal miners, and textile workers lived extraordinarily harsh lives, as well. Coal prices dropped dramatically, as did the demand for ships and ship builders. A

vast amount of the population in North America lived in

squalor and poverty. Most of the people in the U.S.

who did well were stock market speculators, builders,

and owners of consumer goods factories (17).

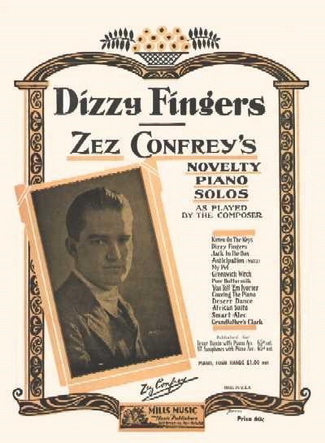

Zez Confrey – the man who started it all

and “invented” the Novelty rag

|

|

The film, The Birth of a Nation (1915), brought about a

resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan,

which terrorized black people in

America after the film’s release

(18). Public lynchings were

mostly a Southern phenomenon

after the late teens with the

number of white people being

lynched decreasing and the

number of black people being

lynched increasing – both significantly (19).

During the 1918 influenza pandemic, protestors sought to end

mask mandates, (20) and the

U.S. president’s office, by never

mentioning the existence of the

deadliest pandemic in history,

ostensibly lied to the public.

Woodrow Wilson eventually

caught the 1918 influenza, then

had a stroke and died in 1924,

quite possibly as a complication

of the disease (21). The Pandemic eventually faded away in

the early 1920s.

Prohibition on the sale of alcohol

in the U.S. brought about a significant increase in organized-crime-

related homicides, burglaries, and assaults, and American cities became violent battlegrounds from 1920 to

1933 (22).

Much as I enjoy watching the silent film comedies of

Harold Lloyd, which depict most of America happily living in opulent homes, driving Stutz Bearcats, and

smoking with expensive quellazaires, (23) that was not

reality for most. That was Hollywood.

So, given that life was financially difficult for most people in North America during the 1920s, how did average income earners manage to get by? And how did

music get made? To answer the second question first,

live concerts and dance music were more in abundance then, and not as prohibitively expensive as they

are today. Wind-up gramophones became more prominent, even though most breakable shellac records

were quite expensive at 75 cents each. Victor went

from zero to 107,000 machines in 1908, and 252,000

in 1912. By 1917, Victor was producing 573,000

Victrolas (24).

In the years leading up to the 1920s, creating one’s

own music at home was, often, the most likely option.

To this end, sheet music became quite profitable at the

turn of the twentieth century.

And from 1900 to 1910

America went from producing

460,000 pianos a year to

1,050,000. In 1919,

338,000 pianos were manufactured, half of which were

pianolas. Pianolas became

popular, despite the increased cost, because a live

instrument could be played

by a mechanical device (25).

But the first question remains

unanswered – where did

most people get the money to

buy these things?

The simple answer is a new

invention of the late 1910s

and 1920s: readily accessible

consumer credit. A plethora

of new household items, including vacuum cleaners,

electric refrigerators, electric

irons, washing machines,

canned food, store-bought

bread, store-bought clothing

all became available to buy in

newly established department stores and supermarkets, and most (including furniture as well) were available on credit. “Buy now and pay later” was a much

used phrase of the time. Installment plans were also

used for buying cars, much as they are today. By the

end of the 1920s, over half of the nation’s automobiles

in the United States were sold using installment plans.

Consumer debt more than doubled between 1920 and

1930. Further, material possessions (quite often ones

which people didn’t really need) were advertised on another new invention, the radio. Advertisers no longer responded to a demand – they

created one as well (26). By

the end of the decade, radio

advertisements during prime

broadcast hours could cost as

much as $10,000 (27).

This was the economic and social world into which Novelty

Piano Ragtime emerged around

1920. A popular music infrastructure (consisting of sheet

music, live concerts and dance

bands, gramophones, and player pianos/pianolas) was firmly

in place, and radio would add to

the mix within a few short years.

Aspiring Classical Pianists

Needless to say, the sub-genre

will be forever mostly associated

with its most famous exponent,

Edward Elzear “Zez” Confrey, and

his first popular success Kitten on the Keys. However,

there were a number of other equally talented players/

composers whom we shall examine shortly.

Confrey was born in 1895 in Peru, Illinois. Like some

other Novelty Pianist-Composers, Confrey had aspirations to being a classical concert pianist and studied at

the Chicago Musical College. By 1916, he was the

staff pianist for Witmarks (Music Company) in Chicago.

And similar to many other Novelty Composers he used

techniques used by composers like Debussy and

Ravel, such as whole-tone scales, consecutive fourths,

and augmented chords. During the early 1920s he

made piano roll arrangements for QRS piano roll company. After the 1920s, he made arrangements for jazz

bands, and he continued to compose until 1959. He

died in 1971 from Parkinson’s disease (28).

Roy Bargy started doing arrangements for

piano rolls and for the Benson Orchestra,

wrote a small number of delightful pieces,

played for Paul Whiteman and later was

Jimmy Durante’s musical director

|

|

Part of the reason for the success of Kitten on the Keys

is because it uses a variation on the “three over four”

rhythmic technique which was discussed a few paragraphs earlier, in rags by George Botsford. But Kitten

also used augmented fourths, consecutive fourths, broken octaves, ninths and tenths in the bass, and a host

of other compositional devices not used in popular or

ragtime piano music until this point. Although Kitten

and My Pet were copyrighted and published in 1921,

Jasen reports having a piano roll arrangement of both

pieces he claims were made in 1918. If this is correct,

then it is probably safe to assume that Novelty piano

ragtime gradually emerged rather

than exploded fully-formed in the

1920s (29).

And although he is most renowned

for Kitten, Confrey wrote a fair

number of other extremely interesting piano rags. Poor Buttermilk is

another one of Confrey’s compositions which is thoroughly inventive

(30).

Another pianist-composer who

once aspired to be a classical pianist but could not afford to study in

Europe was Roy Bargy. Bargy was

born in Newaygo, Michigan in

1894 but grew up in Toledo, Ohio.

He started playing the piano at five

years old and, unable to perform

as a classical musician, he instead

listened to and learned from black

stride pianists such as Luckey Roberts (31). Bargy initially played at

local film houses for silent movies,

but also organized his own dance

bands (32).

As previously noted, the composer-arranger Charley

Straight employed Bargy to arrange piano rolls for QRS.

Bargy became friends with Confrey. He started working

for the Benson Orchestra of Chicago, arranging, playing, and recording with the group until differences with

management led him to strike out on his own as a bandleader at the Trianon Ballroom in Chicago (33). After

disbandment of the new group, Bargy worked for Isham

Jones’ orchestra for two years, then formed another

group of his own. As the 1920s and the Novelty Piano

Rag era waned, Bargy continued to re-invent himself.

He played the piano part and partially re-arranged

George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue in the colour film

The King of Jazz. He accompanied some early recordings of Bing Crosby, worked in radio, then in the 1940s

left Paul Whiteman’s orchestra to work with Gary

Moore, Xavier Cugat, and Jimmy Durante, himself a

very capable ragtime and early jazz pianist. Bargy continued to work fairly constantly until the early 1960s

when arthritis stopped him from performing so much.

He died at his home in California in 1974 (34).

His most popular Novelty rag was Pianoflage. There is

a recording of this work by Fate Marable’s Society Syncopators (35), one of only two recordings made by this

black riverboat dance/jazz band. In it you will hear Zutty Singleton playing the drums (36). Another very effective piece by Bargy is called Ditto (37).

Performing members of jazz bands

In contrast to the previous two pianist-composers,

Rube Bloom (born and died in New York City, 1902 –

1976) was much involved playing in and recording with

jazz bands, where he accompanied, did piano solos,

and also very effective regular and “scat” singing, often

with the greatest jazz musicians of his time. He was

also a musical illiterate – he could not read or write

music, nor had

any musical

education. And

yet his playing

and compositions show the

same inventiveness and harmonic understanding as

both Confrey

and Bargy, and

he wrote some

of the most sophisticated popular songs of

the 1920s (38).

Although he is

best known for a

popular work during the 1920s,

Soliloquy, he wrote and recorded a small number of

other Novelty Piano Rags, one which was extremely

innovative, That Futuristic Rag (39).

Arthur Schutt – the virtuoso’s virtuoso

who arranged for Specht’s Orchestra

and played with The Georgians

|

|

Arthur Schutt (1902 – 1965) was born in Reading,

Pennsylvania, and died in San Francisco, California. At

thirteen he was accompanying silent films, and at sixteen he joined Paul Specht's Orchestra as both pianist

and arranger. He apparently recorded over a thousand

record sides. Moving to the West Coast, he eventually

wound up working in Hollywood films (40). Schutt is

also known as the pianist of the “jazz band within a

band” of The Georgians, which was a sub-group of the

Specht orchestra and recorded for Columbia records.

Schutt’s Novelty rags are among the most virtuosic,

and have not been performed that often, except mainly

in recordings by Schutt, himself. In my opinion, one of

his most attractive pieces is Piano Puzzle (41).

Other lesser known works and composer-pianists

The reader will notice throughout the course of this

article that almost all the composer-pianists (and almost all the Novelty Rag composers were also pianist-

performers) were white. There are manifold sociological reasons why – for instance, the fact that many were

educated in classical music, and the classical music

world was, mostly, a “whites-only” world, as evidenced

by even Marian Anderson being prohibited from performing in most U.S. venues (42). One notable exception to this situation was Clarence M. Jones (1889 –

1949), a black American, who, born in Wilmington,

Ohio, studied at the Cincinnati Conservatory of Music.

He started his own

ensemble in 1917

in Chicago, and

played with a number of bands

(including Clarence Jones’ Sock

Four), and recorded a number of

celebrated early

jazz recordings for

Paramount and

Okeh. He moved

to New York in

1932 where he

worked for Clarence Williams’

publishing house

and later died in

1949 (43).

In the 1910s, he

started his own publishing house and produced a number of piano rags. His one Novelty Rag, of which I am

aware, is entitled Modulations, which he recorded in

Chicago in 1923 (44).

There were also a number of women playing and composing in this idiom, but not receiving as much attention as their male colleagues. Edythe Baker (b. Girard,

Kansas in 1899, and d. 1971 in Orange, California)

recorded a handful of solos and arranged a number of

piano rolls, one of which was Blooie-Blooie, a Novelty

rag which was not released as sheet music or in any

other format (45). She can be heard as an interpreter

on a record she made in 1933, Young and Healthy

(46).

Edythe Baker – a true “rags to riches”

story – from America to

England and back

|

|

Baker was born into poverty and educated in a convent

where she learned music fundamentals. She later

went on to work in a music store, and performed in

Vaudeville and Broadway Musicals in New York. In

1926, she moved to England, eventually marrying and

retiring from the music world (47).

Pauline Alpert (1905 – 1988) was born in the Bronx,

New York, and died there at the age of 82. She wrote a handful of known piano compositions, and was better known during her lifetime as a spectacular

piano virtuoso. Around the age of

seven, she was given some sort of

music education, and by the age

of 11, used it as a supplement to

the family income by teaching students. Her father died in 1919,

possibly from the pandemic, but

she eventually won a scholarship

to study piano at Eastman Music

School, presumably with the aspiration of becoming a concert pianist. But during the evenings, she

would use her advanced musical

training to modify works by

George Gershwin, Felix Arndt, and

Zez Confrey to entertain her colleagues. She moved to New York

City around 1926, and started her

recording and composing career,

as well as arranging some piano

rolls. After the beginning of the

Great Depression in the 1930s,

Alpert found employment in radio.

She was eventually to become

friends with both Confrey and Gershwin. She even

made a “soundie” – a short musical film in 1935 with

Fifi d’Orsay. She continued to work in radio until the

1947, recording a few records after WWII, after which

she married and her career more or less came to an

end until the 1960s. At that point, the newly formed

Automatic Musical Instrument Collector’s Association

discovered her rolls and an interest began in her work

again (48).

Her composition from 1935, Piano Poker (49), is a

good example of both her playing and compositional

skills.

Other composers in the field

As this article is only intended to be an introduction,

there are going to be many more performer-composers

than mentioned here. But another who was fairly

prominent was Phil Ohman (1896 – 1954) who, like

many others here, was told to study music in Europe,

but his father, who was a pastor, couldn’t afford it, so

instead he studied in the U.S. He made countless recordings, including many with Victor Arden, with whom

he formed a piano duo which accompanied many

Gershwin musicals. He later worked in Hollywood writing and arranging scores (50). Nashville Nightingale

(51) by George Gershwin (52) is an example of the type

of duos he played with Arden, and Try and Play It is a

good example of his compositional virtuosity, here

played by Arthur Schutt (53).

Pauline Alpert –

studied “serious”

music at Eastman and then

became a serious

virtuoso, dazzling

listeners on the

radio

|

|

Billy Mayerl (1902 – 1959) was a British jazz pianist

who wrote a number of fine Novelty Rags, including

The Jazz Master (54). Donald Thorne was also from

Britain (55), and composed several good Novelty rags,

including the 1928 work, Spring Feelin’ (56).

The parallel world of Stride Piano

As can be seen, it was mostly white people who were

involved in the composition and dissemination of Novelty Piano Ragtime. There was also a separate world of

virtuoso ragtime music, but played by black Americans,

called Stride Piano. This sub-genre included such figures as James P. Johnson, Thomas “Fats” Waller, Willie

“The Lion” Smith, and “Luckey” Roberts, to name but a

few. But this topic is too extensive to be covered here

and should be discussed in a separate article.

The slow demise and partial return of Novelty Piano

Ragtime

Just as the style developed slowly, and was influenced

by player piano roll arrangements – other media (such

as radio and sound film), and the fact that fewer people learned how to play the piano, changed and ultimately facilitated syncopated piano music gradually

fading into the musical background. Novelty Ragtime

music still lives on in a few individuals. Alex Hassan of

North Virginia is the leading expert in the field today,

being a legendary collector and player in this style. He

has given a number of recitals highlighting his love and

knowledge of this style of music (57) (58) (59).

The late Robin Frost (1930 – 2020) (60) was a stupendous composer in this style, and died only recently.

One often finds in his work not just the influence of

Novelty music, but also stride piano styles and popular

song from the 1930s. His composition, Space Shuffle,

is now often played by younger players at festivals, but

there are several other rags of his that show great imagination and inventiveness, including Windmill Rag

(61).

Robbie Rhodes has also done great work popularizing

syncopated piano music from the 1920s (62). His piano roll arrangements of Frost’s rags also piqued my

interest and resulted in my recording them on my first

compact disc, Space Shuffle and Other Futuristic Rags.

The controversy regarding player piano rolls

In this article, I have deliberately avoided discussing

piano rolls in any detail because there is a controversy

surrounding the concept of “hand-played” piano rolls.

In an article by this author entitled, Debunking Piano

Roll Mythology (63), piano roll maker and authority, L.

Douglas Henderson describes in great detail the reasons why even the “hand-played” rolls were either doctored or edited, and that “hand-played” rolls were

phased out in the early 1920s. He states that it is not

an opinion, but can be categorically proven by visual

examination, i.e. they became “mathematically arranged” and showed a “punch-skip-punch” graph-paper characteristic. Further, he maintained that genuine “hand-played” rolls were labour-intensive and that

rhythm within the measure was always flawed due to

the nature of the recording device. As piano rolls became more and more an arranged medium, piano roll

companies more frequently falsely advertised the

names of famous performers for rolls which were clearly arranged (64).

Issues inherent in this article

The academic documentation of North American Vernacular music is a thorny situation, as evidenced by

many of the issues inherent in this article. For instance, in the music history world, citing liner notes of

records or CDs as sources is verboten. The reason why

is that sometimes the information therein is either

questionable or not correct, and is rarely cited properly.

However, because there is so little information readily

available, anyone who wishes to write on a topic such

as this will often have little choice. And way too many

sources (such as Rags and Ragtime) do not cite

sources at all, let alone properly.

Another issue is that many teachers in academic music

departments tend to look down on popular music –

period – not to mention that from the 1890s to the

1930s. As a result, there is very little finely-honed research which follows acceptable standards of accuracy

and credibility (65).

Clarence Jones (sitting at the piano) – studied “classical” at a time when

only white people were allowed to study or have careers, entered

publishing, organized and played in some legendary Chicago Jazz bands,

wrote a Novelty number and some piano rags, then finally moved to New

York and worked for Clarence Williams

|

|

This may seem like a non-issue to some, but it is supremely important. Truth is always preferable to its

opposite. Informational and academic integrity matter.

As an example, at one of the universities I attended,

one of my colleagues wrote an original biographical

paper on a new composer. This is regarded as the holy

grail of academic research. And yet, when my colleague presented his thesis to his committee, the very

first question out of the mouth of one of the professors

on his committee was how he could know whether the

subject of the thesis actually existed.

This was actually an extremely valid question. A few

years beforehand, that same professor had been a visiting professor at another major university and had

been on a thesis committee there. One of the students

at the other university submitted a thesis on a fictional

person. Its falsity was discovered after the thesis had

been accepted.

Having written historical fiction myself, I can report

from personal experience that it is far harder to create

a fictional history than to simply report facts. In my

opinion, creating a fictional history for the sole purpose

of deceiving one’s teachers is nothing short of perverse. Now, just because someone doesn’t cite their

sources, that does not necessarily mean that that writer is not telling the truth, but it might call into question

the veracity or accuracy of their statements. Sometimes people do lie. It happens.

For the above reasons, it would be very difficult to write

a book on this topic. If it were possible, it would take

many, many years. That, and how all the subjects (and

probably most of their family members, as well) have

all passed on, lends great difficulty to that option. But

my hope in writing this article is that it might inspire

someone else to pursue this matter further.

Finally, public interest in this music is, to put it politely,

limited. For instance, the first issue of my album, The

Graceful Ghost: Contemporary Piano Rags sold almost

2,000 copies. Not much in the grand scheme of

things, but very respectable for a ragtime album (I’ve

had producers brag to me when they’ve sold 200 copies of a ragtime album). By contrast, my album of Novelty rags, Whippin’ the Keys: 75 Years of Novelty Piano

Ragtime, probably sold fewer than 50 copies.

Conclusion

A deadly pandemic, grossly mishandled, and made

more deadly by misinformation. Large numbers of

black Americans being executed outside of the law, a

situation exacerbated by white supremacist extremists.

A prohibition that results in organized crime. Farm and

textile workers working in harsh conditions. A North

American economy balanced on the teetering stilts of

incalculable consumer debt, while a tiny fraction of the

population hoards most of the wealth, ensuring the

inevitability of an economic collapse.

The circumstances of the 1920s sound terrifyingly and

depressingly familiar. And yet, all of it was and is preventable or curable. The negativity of history, that

which causes misery and suffering to millions, need

not be repeated. In the opinion of this author, what

should be repeated instead is that which is positive in

history, such as the use and dissemination of wonderful mechanical devices (like gramophones, music boxes, and player pianos), and the appreciation of glorious

architecture, theater, and artwork. Add to that the fabulous, virtuosic music of the period, Novelty Piano Ragtime, which is, at its worst, not something one would

want to listen to every day, and at its best, delighting,

heart-stopping, and life-enhancing.

*** *** *** *** ***

Matthew de Lacey Davidson is a pianist and composer currently

resident in Nova Scotia, Canada. His first CD, Space Shuffle and

Other Futuristic Rags (Stomp Off Records), contained the first commercial recordings of the rags of Robin Frost. His second CD, The

Graceful Ghost: Contemporary Piano Rags (Capstone Records),

was the first commercial compact disc consisting solely of post-1960 contemporary piano ragtime, about which Gramophone magazine said, “…a remarkably talented pianist…as a performer Davidson has few peers…”.

Selected Bibliography

- Ragtime: A Musical and Cultural History, Edward A. Berlin, University of California Press, 1980.

- Adrian Rollini: The Life and Music of a Jazz Rambler, Ate Van Delden, University Press of Mississippi Jackson, 2020.

- Rags and Ragtime: A Musical History, David A. Jasen and Trebor Jay Tichenor, Dover Publications, 1978.

- The Great Crash 1929, John Kenneth Galbraith, Houghton Mifflin, 1955.

Recommended Recordings in Compact Disc format

Reissues of Original Recordings

- Ragtime Piano Originals: 16 Composer-Pianists Playing Their Own Works, compiled

by David A. Jasen, Folkways RF23, https://folkways.si.edu/ragtime-piano-originals-

16-composer-pianists-playing-their-own-works/jazz/music/album/smithsonian

- Ragtime Piano Interpretations, compiled by David A. Jasen, Folkways RF34, https://

folkways.si.edu/ragtime-piano-interpretations/jazz/music/album/smithsonian

- Ragtime Piano Novelties of the 20’s, compiled by David A. Jasen, Folkways RBF42,

https://folkways.si.edu/ragtime-piano-novelties-of-the-20s/jazz/music/album/

smithsonian

- Early Ragtime Piano, compiled by David A. Jasen, Folkways RF33, https://

folkways.si.edu/early-ragtime-piano/jazz/music/album/smithsonian

- Novelty Ragtime Piano Kings: Rube Bloom & Arthur Schutt, compiled by David A.

Jasen, Folkways RBF41 https://folkways.si.edu/rube-bloom-and-arthur-schutt/

novelty-ragtime-piano-kings/jazz/music/album/smithsonian

- Toe Tappin’ Ragtime, complied by David A. Jasen, Folkways RBF 25, https://

folkways.si.edu/toe-tappin-ragtime/jazz/music/album/smithsonian

- Roy Bargy: Piano Syncopations, compiled by David A. Jasen, Folkways RBF35,

https://folkways.si.edu/roy-bargy/piano-syncopations/jazz-ragtime/music/album/

smithsonian

- Syncopated Impressions of Billy Mayerl, compiled by David A. Jasen, Folkways

RF30, https://folkways.si.edu/billy-mayerl/syncopated-impressions/jazz-ragtime/

music/album/smithsonian

- Zez Confrey: Creator of the Novelty Rag, complied by David A. Jasen, Folkways

RF28, https://folkways.si.edu/zez-confrey/creator-of-the-novelty-rag/jazz-ragtime/

music/album/smithsonian

More recent recordings

- Phantom Fingers, Novelty Piano Music played by Alex Hassan, Stomp Off Records

1322

- Space Shuffle and Other Futuristic Rags, piano solos by Matthew de Lacey Davidson, Stomp Off Records 1252

- Whippin’ The Keys: 75 Years of Novelty Piano Ragtime, Matthew de Lacey Davidson, Capstone Records 8694

Photo credits

- Zez Confrey, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?

curid=1646456

- Arthur Schutt, http://www.jazzmusicarchives.com/artist/arthur-schutt

- Roy Bargy, By Roy Bargy - Sheet music published by Sam Fox Pub.Co., via [1], Public

Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4255064

- Edythe Baker, https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/11/Edyth01-

752x1024.jpg

- Pauline Alpert, https://www.esm.rochester.edu/sibley/specialcollections/

findingaids/alpert/

- Clarence M. Jones, https://syncopatedtimes.com/clarence-jones-and-his-sock-four/

Endnotes

- Berlin, p. 107

- Minute 4:51, Episode 3 of 17, Documentary: All You Need Is Love, directed by Tony Palmer,

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/All_You_Need_Is_Love:_The_Story_of_Popular_Music

- http://www.shoppbs.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/1900/filmmore/reference/interview/

morath_sheetmusic.html

- Berlin, pp. 5 – 9

- Berlin, p. 10

- Berlin, pp. 13 – 14

- Jasen & Tichenor, pp. vii – viii

- Jasen & Tichenor, pp. 21 – 76

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8PrFAP5ipeQ

- Berlin, pp. 188 – 189

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E0mvRf7dvO0

- Jasen & Tichenor, pp. 134 – 170

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LWsIOOIBkzA

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yU_OsXBboKU

- For a more detailed analysis of the history and musical development of Ragtime, I

strongly recommend reading Berlin, pp. 81 – 169

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Great_Crash,_1929

- https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/guides/zw9wb82/revision/4

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Birth_of_a_Nation#Influence

- http://law2.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/shipp/lynchingyear.html

- https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/29/coronavirus-pandemic-1918-

protests-california

- https://www.cnn.com/2020/10/03/us/woodrow-wilson-coronavirus-trnd/

index.html#:~:text=%22Wilson%20never%20made%20a%20public,in%20an%

20interview%20with%20CNN

- https://prologue.blogs.archives.gov/2012/01/17/prohibition-and-the-rise-of-the-

american-gangster/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cigarette_holder

- Van Delden, p. 21

- Van Delden, p. 21

- https://www.ushistory.org/us/46f.asp

- https://www.ushistory.org/us/46g.asp

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zez_Confrey

- Berlin, p. 168, NOTE 26

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EmSj4z8mT10

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3OYENetpEHA

- Roy Bargy: Piano Syncopations – LP and CD Compiled and Annotated by David A. Jasen, Folkways records RBF-35, Liner notes by David A. Jasen

- http://chicagopatterns.com/trianon-worlds-most-beautiful-ballroom/

- http://www.perfessorbill.com/comps/rbargy.shtml

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jP_HGqbDTP4

- https://syncopatedtimes.com/fate-marables-society-syncopators/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=90V6gBlv3vA

- Novelty Ragtime Piano Kings, Folkways Records, RBF-41, Liner Notes by David A. Jasen

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZumZUeTyxOk

- Novelty Ragtime Piano Kings, Folkways Records, RBF-41, Liner Notes by David A. Jasen

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bGRYVrJYvSA

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marian_Anderson#1939_Lincoln_Memorial_concert

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clarence_Jones_(musician)

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2VxnipsAmAI

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qZIrZGeNC5Y

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ikXTQUc5FmU

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edythe_Baker

- http://www.perfessorbill.com/ragtime4b.shtml – On Bill Edwards’ website, Ed-

wards invites the reader to write to him and request research notes and sources

not cited on his website. Edwards did not respond to my email request for this

information, sent August 22, 2021

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2jaoGSxNLUg

- http://ragpiano.com/comps/pohman.shtml

- The listener will note that the ending quotes two bars from the introduction of

Pork and Beans by Stride pianist-composer Charles “Luckey” Roberts.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sDMgw5tjWTI

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gl9Q0WFbV5I

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W15PJAdoiJw

- Early Piano Ragtime, Folkways RBF 33, Liner Notes by David A. Jasen

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jzICG4KgW00

- https://archive.org/details/PurpleMotes-AlexHassanMasterOfNoveltyPiano842

- http://www.nvrs.org/AlexHassan.htm

- Alex Hassan did not respond to my email request for confirmation of information

in this article, sent August 22, 2021

- https://syncopatedtimes.com/ragtime-composer-robin-frost-has-died/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m5s46uLV6k8

- https://www.westcoastragtime.com/bios/bio.rhodes.04.htm ,

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3VbkLAD_ifE

- Article published in The Mississippi Rag, October 1997, pp. 14 – 17

- Debunking Piano Roll Mythology, Matthew de Lacey Davidson, The

Mississippi Rag, October 1997, p. 17

- To see more about correct academic procedures, please read the

following: https://www.nhcc.edu/student-resources/library/

doinglibraryresearch/basic-steps-in-the-research-process

|