|

Edison the Man and His Life (Part One): The First 30 Years

by Mike Bryan

This is Chapter I in a series that looks at the life of Thomas Edison. Chapter II will be published in the upcoming APN Summer issue.

|

|

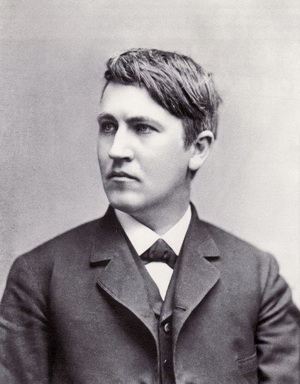

Tom, 1851

|

|

|

Hands up if you knew that Thomas Edison was the inventor of the phonograph.

Looks like everyone, but how many of us know much about him? You probably know

that he was an intense, focused man and prolific inventor, but may not know how

his life unfolded, or about the challenges that shaped his character and style.

Curious about the man himself, I gathered a few books and read them cover-to-cover

to learn about Edison’s life and what made him the man he was. It would also help me

to decide how I really felt about him. My reading certainly filled in a lot of gaps

in my factual knowledge, but also helped my understanding of Edison’s motivations,

strengths and weaknesses. Indeed, I feel that I now know Thomas Edison as a human

being, not just as an inventor. In fact, the term "inventor" may tend to create a

stereotypical image that can obscure other qualities, but more about that later.

Anyway, having been fascinated by what I’d learned, I agreed to share my knowledge

and conclusions by distilling it into two presentations that I made at CAPS in

February 2015 and May 2016. The purpose of this and a subsequent article is to

present that distilled information in a readable format that will hopefully help

you know and understand Thomas Edison. I found myself drawing the information for

my articles more from "Edison: A Biography" by Matthew Josephson than any other book.

I can only explain this by saying that Josephson’s account seemed the most credible

to me and provided the most insight into Edison’s personality and behaviour.

Edison Family Background

In 1730 John Edison arrived in the British Crown Colony of New Jersey from the

Netherlands as a child with his single mother. In 1765 he married Sarah Ogden

and became proprietor of a farm. John Edison was a Loyalist during the revolutionary

times of the 1760s - 1780s and got caught up in the struggle, refused to take an

oath of allegiance to the American revolutionaries, was convicted of treason and

sentenced to death in 1778. He was then paroled, however, perhaps because his wife

Sarah’s family had supported the revolution, aka the American War of Independence.

Nevertheless, the outcome of the Revolution meant that John Edison’s property was

confiscated and in 1783 the family was forced out of the country with 35,000 other

Loyalists, some going to the West Indies and some to Canada. His loss of property,

because of his devotion to the Crown, made him eligible for a land grant which

provided him with land near Digby in Nova Scotia. The Edisons worked there for 28

years, John and Sarah producing many sons and grandsons. The eldest son, Samuel,

married Nancy Stimpson of Digby in 1792.

|

|

Tom at about 15

|

|

|

Samuel and Nancy had eight children, one of whom was Sam Edison Jnr in 1804. By

1811, the clan of 19 Edisons had outgrown their land and responded to the call

for people to spread westwards. The Edisons were granted 600 acres in Ontario

on the Otter River, about 3 kms inland from Port Burwell on Lake Erie.

The following year, in the War of 1812, Samuel Edison Snr was involved as

a Captain and did well for the British-Canadian forces.

Peace brought more immigration and by the 1820s the Edison settlement

had become a village. Samuel Edison Snr donated land for a main street,

church and cemetery. Colonel Burwell, who had made the land grants, had

named the village Shrewsbury, but the villagers didn’t like it and asked

Samuel Edison to rename it. He chose the name Vienna. The Edisons were

not educated people, but well regarded as hard-working pioneers – farmers,

lumberjacks and carpenters. They were also known for their family traits

of individualism, obstinacy and contrariness.

Sam Edison Jnr worked as a carpenter, tailor and tavern-keeper. His

tavern in Vienna became a centre for rebellious conversation. He did

not share his father and grandfather’s views on loyalty to the British

and he sided with the agitators wanting greater autonomy. In 1828 he

married Nancy Elliott, built a new home in Vienna and soon had four children.

Political agitation continued and, in 1837, Sam Edison

Jnr led rebels from Vienna and Port Burwell towards

Toronto to join William Lyon Mackenzie’s rebellion to

overthrow the Royal Canadian Government. When he

learned that the insurrection had been routed, he hurriedly

dispersed his band and headed for the American

border, crossing the frozen St Clair River to Port Huron.

So the rebellious descendant of British Loyalists, who

had been driven from New Jersey to Nova Scotia, was

now driven from Canada to America, making it two exiles

in three generations. Although things calmed down

in Canada with political reform, Sam Edison Jnr would

have been arrested if he had ever returned.

The American mid-west was developing fast. It was materialistic,

inventive and progressive. That prompted

Sam Edison Jnr to find his way to Milan, Ohio, at the

end of a canal about 12 kms south of Lake Erie. It was

a booming grain port where ships were loaded before

entering the Great Lakes waterways. There Sam Jnr

developed a good business supplying shingles for the

grain warehouse roofs. By 1839 Sam and Nancy had

produced two more children, but within a few years

those two and another sibling had died, due to poor

health and harsh winter conditions.

|

The Chicago, Detroit & Canada Grand Trunk Junction

Railroad was chartered in Michigan on 25 March

1858 to build a 60 mile 67 chain railroad from Fort

Gratiot, just north of Port Huron, Michigan, to West

Detroit. The President was Thomas Evans Blackwell

(1819-1863), who was also the first Vice President

and General Manager of the Grand Trunk Railway of

Canada. The line was constructed between 1858 and

1859. In 1859 the Grand Trunk Railway completed its

line to Sarnia, Ontario, and instituted a ferry service

across the St. Clair River to Port Huron, Michigan. The

Grand Trunk Railway took a lease on the Chicago,

Detroit & Canada Grand Trunk Junction Railroad,

which remained a nominally independent company

until 1928 and then became part of the Canadian

National Railway's US subsidiary, the Grand Trunk

Western Railroad. It was on the line from Port Huron

to Detroit that a 12-year-old Thomas Edison held his

first job as a newsboy and candy seller on passenger

trains. John Speller's Web Pages - US Railroads

|

|

|

Edison’s Childhood

Nancy was of Scottish-English heritage and different

from the Edisons, being more intelligent and with a devotion

to learning and religion. Well into middle age

she had her seventh child, born on Feb 11, 1847,

named Thomas Alva, the Alva being in honour of a family

friend, Captain Alva Bradley. Thomas was sickly as a

young child, but mischievous, inquisitive and somewhat

difficult, as well as a bit of a loner. His brothers

and sisters were much older, the younger ones having

died. His father didn’t relate well to him, seeing him as

stupid and lacking in good sense. Thomas sensed his

disappointment and disapproval.

In 1853, boomtown Milan suffered a change of fortune

when the new railroad bypassed it and replaced the

canal as the best way to move grain into the Great

Lakes waterway. There was no longer any work for the

now well-to-do Sam Edison, so the family moved to Port

Huron. He had learned that the railway was to be extended

north from Detroit to Port Huron, Michigan and

thought that he would be able to do well there again in

lumber and grain.

Young Thomas did poorly at school, not being allowed

to think freely, resentful of his teacher and conscious

of his father’s disappointment. It may have been for

these reasons, or because his father couldn’t pay the

school bills, but it was decided that his mother would

school him. She had little teaching experience, but understood

Thomas and his interest in learning. They got

on very well and she inspired him to learn. Later in life

Thomas would tell others, "My mother was the making

of me."

Thomas was happy, mischievous and a practical joker,

but his father felt he missed a normal boyhood. Around

the age of ten, Thomas began making chemical and

electrical experiments. He also became fascinated by

electromagnetism and telegraphy, making his own telegraph

model and practising Morse code when he was

eleven.

In 1859 the long-awaited railroad to Port Huron was

opened. Thomas needed money to expand his laboratory

and at twelve got himself a job as a newsboy selling

snacks and newspapers on the Grand Trunk Railway

train between Port Huron and Detroit. He soon expanded

his offerings to include fruit and vegetables

and other items to meet travellers’ needs. He would

see a lot of life on the train and in the rail yards, leaving

home at dawn and not returning until late at night.

His parents seemed to accept that he worked, perhaps

because he had already made the break from traditional

schooling and because of his deafness. This hearing

condition was quite serious by the time he was twelve,

so there really was little chance of any further schooling.

The deafness was most likely caused by scarlatina

and periodic subsequent ear infections. It caused him

to be more solitary and serious than others, and led to

him reading and self-educating in a more consistent

and determined way. At fifteen, he studied Newton’s

principles, but couldn’t grasp them and was left with a

permanent distaste for math. Other reading subjects

were chemical analysis and practical mechanics. It was

during this period that Thomas developed a disdain for

theorists and favoured the practical side of science.

His isolation provided time to think and he formed

strong views at this time on theoretical and applied

science. Indeed, it was the strength of his conviction on

this that guided his future direction and purpose in life

as an inventor.

|

|

Young Tom Edison

|

|

|

During the Civil War he observed that more newspapers

sold when headlines were dramatic, e.g. battle

news. So he started to check the Detroit Free Press

headline proofs. One day when he saw news of a big

battle, he asked telegraphers to wire a short bulletin

for display on bulletin boards at the train stops along

the line, to pique the interest of the waiting passengers.

Then he went to the newspaper editor and asked

for 1000 copies, on credit, instead of his usual 200.

Arriving at the first station and seeing crowds, he

raised the price by 10c, at the next station 15c and

later, as he was running out of newspapers, by 25c. On

reaching Port Huron, he was able to auction the remaining

papers to the highest bidder!

Thomas realised that telegraphing ahead had done the

trick and from then on he wanted to be a telegrapher.

He could hear the clicks clearly, but not the ambient

noise or other distractions. He began to experiment

with telegraphy at home, stringing up long lengths of

wire between his house and a friend’s, half a mile

away.

Thomas was constantly enterprising and inventive, but

always poor and needing money for his experiments.

He was just fifteen when he bought a printing press

and started his own newspaper on the train – The

Weekly Herald. He expanded the paper into a kind of

gossip rag called Paul Pry. However, after one story

offended someone, resulting in Thomas being thrown

into the St Clair River, he ceased publication. Besides

which, his lack of formal education had shown through

in his atrocious grammar, punctuation and spelling.

Another adventure in 1862 led to the next stage of his

young career. It resulted from an incident when he noticed

the stationmaster’s 3-year old son playing on the

train track and rescued him just before a train came.

The stationmaster was very grateful and offered to

teach him to be a telegraph operator.

As a fifteen-year old, Thomas was cheeky, aggressive,

competitive and mature, but boyish, too. Although a

loner driven by curiosity in his experiments, his observations

of life made him worldly, calculating and

shrewd. His poverty and focus meant, however, that he

didn’t bother to dress well and he was regarded by others

of his age as a bit of a country hick.

|

|

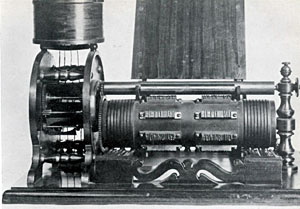

Edison patented his first invention,

an electric vote

recorder, in 1869.

(Photo courtesy of the Edison National Historic Site)

|

|

|

Growing Beyond Childhood

After the stationmaster’s teaching reward, Thomas

found work as a telegraph operator in Port Huron. After

a year there, he was posted to Stratford Junction in

May 1864 as a railway dispatcher. He worked the night

shift, which was not busy, so he was able to continue

his studies. He got into trouble, though, when he was

found to have devised a clockwork automatic transmission

set-up to indicate that he was on alert…when he

wasn’t. He did this so that he could take catnaps during

the night and be awake all day. He received a severe

reprimand for this. Not long after, he was ordered

to hold up a freight train, but was unable to contact the

signalman in time, nearly causing a head-on collision

between two trains. He was summoned to the stationmaster’s

office and accused of negligence, but managed

to slip away when the stationmaster was distracted.

He jumped on the fast train to Sarnia and took the

ferry across to Port Huron.

Over the next few years, Thomas worked in telegraph

offices in Cincinnati, Louisville, and Indianapolis. Later,

in 1864, he created a message-repeating device so

that if anything was missed the first time, the message

could be replayed more slowly for greater accuracy…

until it broke down one day at a critical time. After the

Civil War ended, he worked in Nashville, then Memphis,

where telegraph operators were in high demand

and well paid. After being fired in Memphis because his

now-perfected repeater bested the one that his boss

was working on, he went back to Louisville and settled

there for a year or so. He remained obsessed with telegraphy

and electricity and began to see himself as an

aspiring inventor. He would get fired from jobs because

of his distraction with his own interests, even though

he was recognized as a blazingly fast telegrapher.

Desperate for the money he needed for his experiments,

Thomas almost joined two colleagues on a venture

to Brazil where telegraphers were in great demand

and very well paid. After setting out, he met someone

in New Orleans who convinced him of the dangers

ahead and he returned to Louisville. His two colleagues

died of yellow fever while travelling through Mexico.

|

|

Edison's Telegraph patent, June 1869,

Edison

Muckers

|

|

|

Becoming an Inventor

Thomas returned home to Port Huron, finding his mother

suffering from her hard life, old before her time and

losing her mind. His father was not around much.

Thomas didn’t want to stay there and decided that he

would work in the east after a friend from his Cincinnati

days had written from Boston. Boston was a hub of

culture and scientific learning – the kind of place he

needed to be.

Finding himself a job at Western Union in Boston,

Thomas worked during the day while studying and experimenting

at night. He became fixated with the idea

of multiplex telegraphy, i.e. sending and receiving multiple

messages simultaneously through the same wire.

He was able to make the most of Boston by visiting

other young scientists in the area who were working on

telegraphy and electrical instruments. Within a year or

two, Alexander Graham Bell would set up shop there to

work on the idea of the "speaking telegraph". Thomas

was able to attract his investors to fund his own work

and he reached a point where he was able to set up his

own shop. He appears to have paved the way for his

resignation from Western Union after one of his pranks

prompted his manager to downgrade him. So this was

it - Thomas Edison was now a full-time freelance inventor

devoted to bringing his inventions to market.

He managed to get $500 from an investor to develop

his duplex telegraph. He then received $100 from another

to help develop a telegraphic vote-recording machine.

For this he filed a patent in 1868 and was granted

his first of many patents in June 1869. He had observed

how long it took for votes in Congress to be

counted, with each member in turn declaring Aye or

Nay. His invention would provide two buttons at every

member’s seat and the results would be displayed on a

board. He expected to sell this to state legislatures and

both houses of Congress and make at least $50,000,

but everyone he approached rejected it flatly for political

reasons. He was devastated, but learned that in

future he must work only on products likely to have

commercial demand – not because he wished to acquire

wealth for himself, but because he wanted the

glory of developing new inventions of practical use.

|

|

Edison Stock Ticker

|

|

|

After the Civil War, the stock market became busier

and there was a need for speeding up the transmission

of the ever-fluctuating stock and commodity prices. A

telegraphic device known as the "Stock Ticker" had already

been invented, but Edison made refinements

and was granted his second patent. Then he persuaded

a company to rent his stock ticker to subscribers,

while he helped in the stringing up of wires between

their locations and the stock exchange. This venture

went bad when his investors fell out and his patents

got sold to a large telegraph company, leaving him with

almost no return. At this time he also made and sold

private telegraph machines for sending and receiving

messages between two locations (essentially a nonspeaking

telephone).

Back to the duplex telegraph idea – there was already

a system available from another company and Western

Union had bought the patents. Undeterred, Edison

worked on improvements to his own system before

asking Western Union to shut down their system and

hook up his for a trial. They refused, so he approached

a rival, the Atlantic & Pacific Telegraph Co., and persuaded

their manager in Rochester to let him use the

line between there and New York City. He raised $800

from a Boston investor and proceeded to set up in

Rochester in April 1869. He was, however, never able

to make contact with New York and he found himself

having used up any remaining goodwill in Boston. It

was now time to move on.

|