|

The Development of Chinese Records from the Qing Dynasty to 1918

by Du Jun Min

G&T

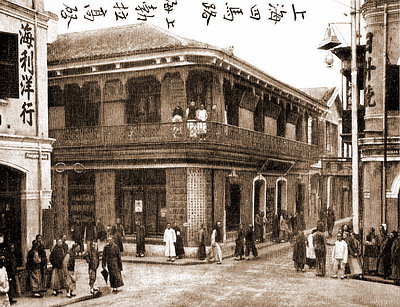

Fred Gaisberg made 476 Chinese recordings in Shanghai and Hong Kong in 1903. These records were first sold in China through S. Moutrie & Co.

The arrival of these records was announced by an advertisement in the Shanghai daily "Shen Bao" on July 10, 1903, just four months after

Gaisberg ended his recording trip to China. In 1906, S. Moutrie & Co., as an official agent for Victor for the entire Chinese market, started

selling Victor's gramophones and records through Foong, Yuen Sing who operated this business from the office of S. Moutrie & Co. Ltd., in a

building at 3 Nanking Road, near Nanking Road and the Bund (a Huangpu River beach) corner in Shanghai.

|

|

Fig.a Detail of Fig.1 record showing 'o' on matrix

|

|

|

Some of these recordings were continuously re-issued by Victor in the United States in the 6500, 6800 and 42000 series. According to Ted Fagan

and William R. Moran's book The Encyclopedic Discography of Victor Recordings - Pre-Matrix Series, and some actual discs in my collection,

69 records in the A-6501 to A-6569 series were re-issued as 7" discs and 61 records in the A-6800 to A-6862 series were re-issued as 10" discs

in 1904, with the yellow "Velly Good Talkee" trademark label. There were another eighteen of these re-issues, of music from Shanghai, that were

issued with yellow "Yi Cuo" labels in 1908. G&T Chinese records issued before 1908 were made in Hanover, Germany, but by 1908 some were made in

Hayes, England, after its commercial pressing operation started in July 1908. Issues after 1909 were made by Gramophone's Calcutta factory, which

was officially opened in December, 1908.

Following Fred Gaisberg's first recording trip to China in 1903, G&T often sent its recording experts to the Far East for recording purposes.

In March, 1905, eighteen recordings in the Tibetan language were made by William Sinkler Darby in Calcutta. During January, 1909, some Chinese

recordings were made by another G&T expert, George Walter Dillnutt, in Singapore and Macao. Forty-eight records made in this session appeared in

a G&T catalogue issued in 1909. These records used matrix numbers from 10356o to 10407o (Fig. a) and were issued in the 7-12000, 7-13000 and the

7-14000 series (Fig.1). In March, 1910, Dillnutt recorded forty-two Chinese discs in Bangkok using the same series numbers as those of 1909. In

late 1911, Max Hampe recorded another lot of Chinese records in Singapore, Hong Kong and Macao using matrix numbers either in the 10XXX or the H10XXX

series (Fig.2). In 1906, William Gaisberg visited Hong Kong to make some Cantonese recordings, but the actual number he made is uncertain. From around

1915, Chinese records started to have an HMV label.

|

|

Fig.1 10" double-sided ca. 1909, Macao

|

|

|

|

|

Fig.2 10" double-sided, ca. 1911, Singapore, HK or Macao

|

|

|

Under the old social system of the late Qing Dynasty, men's social status was much higher than women's - men were greatly respected and women were

not respected. Music was mainly performed by courtesans in metropolitan tea houses, taverns and brothels, but for those people who did not live in the

bigger cities, performances were given in open-air theaters (Fig.3). The Chinese opera recordings were made by males, while the recordings made by

courtesans were of popular tunes.

|

|

Fig.3 An Open-Air Theater in Hankou, ca. 1906

|

|

|

Victor

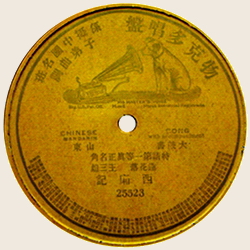

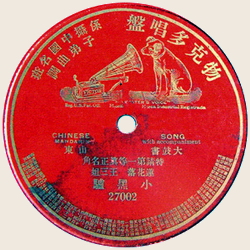

While Victor first made recordings in China on 10" discs in the 7324-8299 series in early 1905, the 9100 to 9234 series (which carried matrix numbers

from 1001 to 1135) (Fig.4) and the 10000 to 10350 series of 12" records were recorded at approximately the same time, in 1905. The labels on the 12"

records had variegated yellow, red, blue and green colours. From 1908 to around 1910, some new recordings were issued in the 22000, 25000, 27000 and

28000 series. The 22000 (Fig.5) and 25000 (Fig.6) series were on 10" single-sided discs and the 27000 and 28000 series were on 12" single-sided discs

(Fig.7). Many of the 10" records were later re-issued by such Japanese recording companies as the Imperial Graphophone Company (Fig.8) and the Sister

Talking Machine Co., Ltd., of Osaka, Japan (Fig.9). The Oriental Phonograph Mfg. Co., using Chinese records patented by Keiko & Co., Japan, also issued

some Chinese discs during 1914-1915 (Fig.10).

|

|

Fig.4 12" single-sided, ca. 1905

|

|

|

|

|

Fig.5 10" single-sided, ca. 1908-1909

|

|

|

|

|

Fig.6 10" single-sided ca. 1908-1909

|

|

|

|

|

Fig.7 12" single-sided ca. 1908-1909

|

|

|

|

|

Fig.8 HIKOKI record, 10" single-sided ca. 1913

(Courtesy of Lee Kuen Chung)

|

|

|

|

|

Fig.9 10" double-sided ca. 1914-1918

(Courtesy of Lee Kuen Chung)

|

|

|

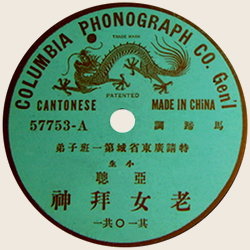

Columbia

Most early Chinese discs recorded by Columbia were arranged for by J. Ullmann and Co.'s offices in Shanghai and Hong Kong. In June, 1904, to launch a

new recording plan by Ullmann and Co.'s offices, Columbia sent Charles. W. Carson, a recording expert from Ohio, to Shanghai. Carson's work was under

the direction of a Mr. Stanley, who was then at Columbia's office in San Francisco and later became the manager of the Oakland Branch. Carson's recording

program was also arranged by Stanley, the music chosen by Chinese consultants. Columbia sent all of the recording equipment and accessories to Shanghai

aboard the S.S. "Coptic", and the shipment arrived in Shanghai that November.

With the equipment received, Carson made recordings of Chinese northern operas in Shanghai until March, 1905, and then recorded Cantonese opera in

Hong Kong from April to August of that year. From June 1904 until September, 1905, Carson had spent a total of fifteen months in China, making hundreds

of records, but many of them were unacceptable in quality. The Chinese northern operas were issued in a 15000 series with catalogue numbers from around

15500 to 158XX, principally on two different labels. One was with the American flag and Chinese Qing-Dynasty's dragon flag label (Fig.11), and the other

was with the name "Ullmann and Co.", the sales agent in China, but in Chinese characters (Fig.12). The Cantonese operas were issued in a 57000 series

with catalogue numbers from 57500 to 576XX and the label had a golden Chinese dragon on a red background (Fig.13). Because of problems with masters and

grooves, these recordings were not satisfactory to Ullmann. In the meantime, Carson was asked by his headquarters in San Francisco to go to Japan by the

first available ship for more recording activity, where he would work together with Harry L. Marker, under the direction of F. W. Horne.

|

|

Fig.10 Oriental record, 10" double-sided

1914-1915

(Courtesy of Luo Ning)

|

|

|

|

|

Fig.11 10" single-sided ca. 1905

|

|

|

|

|

Fig.12 10" single-sided ca. 1905

|

|

|

|

|

Fig.13 10" single-sided ca. 1905

|

|

|

Ullmann

In early 1907, Carson returned to Shanghai to complete his unfinished recordings. I believe that the recordings made in this session were issued in a

60000 series with catalogue numbers from 60000 to 605xx for the Chinese northern operas, with a label similar to those of the 15000 series. Around May,

he moved to Hong Kong to be an assistant to Harry L. Marker for a new recording session. Recordings made in this session were issued in a 57000 series

with catalogue numbers ranging from 57700 to 578XX, and the labels had a golden Chinese dragon on a green background (Fig.14).

|

|

Fig.14 10" double-sided ca. 1907

|

|

|

These recordings covered

Chinese southern operas, such as Cantonese operas, as well as those from Amoy, Swatow and Hong Kong. Harry L. Marker spent a year, from about May, 1907,

in Shanghai, Hong Kong, Beijing and Tianjin. Part of the time he worked with Carson and part of the time he worked alone. Columbia's other recording expert,

Charles J. Hopkins, made a globe-trotting trip from Britain in October, 1903, staying in China for about one month in 1904, but he seemed not to have made

any recordings at that time.

J.Ullmann and Co.'s offices in Shanghai were located at No. 564 Nanking Road, in Tientsin inside the French Concession and in Hong Kong at 74 Queens Road.

All of the recordings cut for Ullmann were sent to the United States for pressing in Bridgeport, CT. by the American Graphophone Company under the direction

of T.H. Macdonald. The finished discs were then sent back to China for sale by J. Ullmann and Co., the agent for the Chinese market. The records made in

Hong Kong in the 57000 series were of Cantonese and Southern operas, and were targetted to Cantonese consumers in Hong Kong, but also to those emigrees in

the U.S., Canada and South-East Asia. Because some were destined for the diaspora market, there was no mention of the name of the Ullmann agency on those

labels. Since few in the Chinese diaspora were from northern China, the discs of northern opera were sold only inside China.

Pathé

Pathé's Chinese records first appeared on the Chinese market in 1908. These centre-start discs were double-sided, vertical-cut with an etched-label, and

most of them were 11.5" in diameter. They had stamper letters (in capital letters) accompanied by a series number, placed directly below the names of the

artists and titles, and the recording dates can be determined from the stampers.

|

|

Fig.15 Si Ma Road, also called Foochow Road

|

|

|

The early stamper designations from 1908 to 1909 had the letter "R" accompanied by a series number in the 24000 to 26000 series. Later in that period the

letters "N" and "R" both appeared on the 25000 series. Around the 45000 series, the "R" was replaced by the letters "GR", until the 60000 series in 1910.

From about the 65000 series in 1911, a new combined stamper designation "RA" appeared on the platter and that was used on the 65000 to the 99000 series,

from the years 1911 to 1914. At the same time, the letters "ER" were used in the 82000 series, and the letter "B" was used in the 97000 series, even though

for a short time they were both used. Starting in 1914, a new stamper number/letter style was created, the (14)-PM with a code number suffix. In 1915, it

was changed to (15)-PM. From 1915 onward, Pathé ceased using the center-start system and was working with their new edge-start discs.

All Pathé Chinese etched-label records carry catalogue numbers either in the 32000 or in the 35000 series. The 32000 series was used for the Beijing opera

and for other local operas, while the 35000 series was used for Cantonese operas.

The first Pathé records available on the Chinese market included some 800 Pekinese recordings with catalogue numbers from 32001 to 32758 (some records bore

the same catalogue number on both sides, when both sides carried pieces from the same opera, and they therefore appended -1 and -2 as suffixes to the number)

and 200 Cantonese recordings with catalogue numbers ranging from 35000 to 35199. Later, many new recordings were released bearing different Chinese variants

of the Pathé tradename on the labels at different times, and the tradename was sometimes translated into Chinese characters as "Compagnie Generale Phonographique

Pathé Frères".

|

|

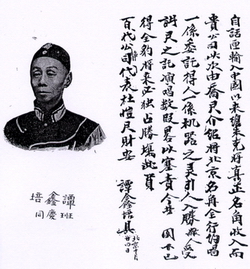

Fig.16 The letter from Tan Xin Pei to Du Kai

|

|

|

The first Pathé Chinese etched-label records were made in France, as shown by a lozenge stamp on the platters. Later, from about 1910 to 1914, they were pressed

in Belgium. All of these discs were recorded in China, their masters sent to France and Belgium for pressing and the finished discs were returned to China for sale.

Pathé's office in Shanghai was first located at No. 99 Szechuen and later they had another address at 58 Si Ma Road. Si Ma Road was near Zhong He Li, a place

that was bustling and noisy. This area was where most of the famous newspaper offices were, there were tea houses and brothels and the literary scholars congregated

there. It was a place both of culture and of prostitution. Because of a tale involving a very famous literary scholar and a prostitute, which took place in that road,

the local people called the prostitutes in that area the "La Traviata" of Si Ma Road. Some people thought of it as the birthplace in China of western industrialization

and culture in modern times, since it was an area where foreign concessions (including the British concession), foreign commercial offices and publishers were

concentrated, all bringing in influences from abroad. A view of the centre of Si Ma Road is shown in Fig. 15.

In a letter from Tan Xin Pei to Du Kai (Fig.16), Pathé's representative in China, bragged that Pathé was recording all of Beijing's famous opera artists. Tan Xin

Pei was the most famous Beijing opera artist at that time. He created the Tan artistic style of singing at the Beijing opera and this tradition has been faithfully

handed down to his own sixth generation descendants, right to this day.

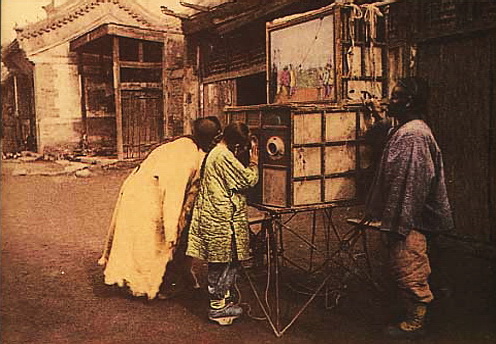

Figure 17 shows a young black man operating his peepshow on the street for two Chinese fellows in the era of the late Qing Dynasty. These two young men with

long braids hanging down their backs are looking into the machine with great curiosity. Andrew F. Jones in his book Yellow Music, Media Culture and Colonial

Modernity in the Chinese Jazz Age, says that the Frenchman E. Labansat set up a peepshow for Shanghai theatre-goers. If that was indeed the case, the peepshow

the young black man is operating could be the very business that Labansat owned before he started selling records on the street in Shanghai.

|

|

Fig.17 Peepshow on Street, late Qing Dynasty

|

|

|

Nipponophone

In March, 1910, Japan sent a group to visit the London International Exhibition where they invited the recording expert George L. Holland, an English-American,

to Japan to make recordings. Holland was later loaned by Nipponophone Company for a period of five months to make recordings of Chinese performers. Around

March and April, 1914, Holland made approximately 200 recordings in Osaka of people from Formosa (Taiwan) and these discs in a 4000 series were the first

recordings ever made by Taiwanese.

After Holland had finished his recordings in Japan, he cut some 100 records in Tianjin, China, during May and June, 1914, under an arrangement with Nipponophone's

office in Dalian. These recordings were issued in an 8000 series with different trade marks, such as Symphony (Fig.18), Royal (Fig.19) and Nipponophone (Fig.20).

They are double-sided and 12" in diameter. The masters were sent to Kawasaki, Japan, for pressing, but when the master discs were inspected for clearance at

Kobe customs, many were found to be broken. They were able to press only 10,000 records from the surviving good masters, and these discs were sent to Shanghai

for sale. For these discs a special "ENGLE" trade mark was registered in Shanghai by Nipponophone's office at 53 Szechuen Road. Because of low sales, these

records were then transported to Taipei. Unfortunately, they still did not sell well there and finally had to be sent back to Japan. A further plan was hatched

to send these records to Dalian for a final sale, but a big fire completely destroyed the warehouse where they were stored. The surviving records are extremely rare today.

|

|

Fig.18 12" double-sided ca. 1914

|

|

|

|

|

Fig.19 12" double-sided ca. 1914

|

|

|

|

|

Fig.20 12" double-sided ca. 1914

|

|

|

I must express my gratitude to Lee Kuen Chung, a researcher and collector of early records from Taiwan. During the writing of this article, he was kind enough

to supply me with a great deal of information about Chinese records made by Japanese recording companies, as well as with copies of the excellent articles that

he had previously written.

Sincerely,

Du Jun Min

Buenos Aires, Argentina

December 2008

|