|

Music, Money and Songwriters:

ASCAP and its relation to Jazz and R&B Songwriters in the 1930s

by Mark Quail

Anyone with even a passing interest in

the music business has heard stories of

musical artists not getting paid their due

for their work. There are loads of stories of the

early rock n’ rollers who had some big hits in

the fifties but ended up wasting away in some

trailer park in their later years. Those stories

are usually replete with the usual bogeymen:

the bad record companies that did not pay

royalties and the crooked managers who took

advantage of their clients.

As I read more and more about music industry

history, I noticed references to suspect dealings

that were not just from the usual suspects but

also from music industry trade groups, the

organizations that played larger overreaching

roles in the music business. Particularly an

organization called ASCAP. My investigation

into this was triggered by several comments

found in the following books:

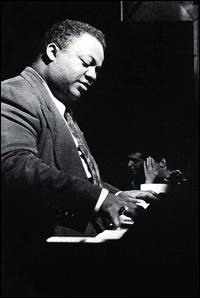

In Peter Sylvester’s excellent work on the

history of boogie-woogie piano, he writes

regarding Meade Lux Lewis:

In 1941, after having been rebuffed by ASCAP

for a membership, famed boogie-woogie

pianist-composer Meade Lux Lewis’s cause was

picked up by Downbeat Magazine. Mr. Lewis

was the composer of such songs as “Yancey

Special” and “Honkey Tonk Train Blues”, both

of which were commercial hits and sold over

500,000 records. Downbeat printed articles

about the situation in 1942 and eventually

embarrassed ASCAP into allowing him to join.

Reasons for the refusal were never given and it

can only be guessed that it was either another

manifestation of the "Jim Crow” mentality

discrimination against Lewis, or a misguided

view that boogie-woogie compositions were not

taken seriously as music. [1]

|

|

Meade Lux Lewis

|

|

|

Mark Coleman hints further at what was going

on at the time in his book on the history of the

music industry:

Formed in 1939, BMI emerged as ASCAP’s

eager sibling, younger and hungrier. BMI

existed to service the needs of local radio

stations and at the same time promote regional

music. BMI also lifted the bar on song

publishing: the list opened up to small-label

performers – that is, "hillbilly” and black

– which’d been excluded by ASCAP. [2]

Finally, in Rick Coleman’s vivid biography of

Fats Domino, he comments about events in the

1930s when writing, "… the exorbitant royalty

demands of the music publishing monopoly

ASCAP, led the radio networks to form BMI

which, in sheer desperation for songwriters, did

not discriminate.”[3]

Discrimination? Exclusion? Refusal? "What

was going on here?” I asked myself as I set

out to investigate. Who or what was ASCAP?

Well, ASCAP is the acronym for the American

Society of Composers Authors and Publishers.

They are a trade organization of music

publishers. They function to license music

and collect royalties arising from the public

performance of music, whether that be live

performance or performance on TV or radio.

BMI is a similar-styled organization. They are

organized to collect the same type of music

royalties. Their acronym stands for Broadcast

Music Inc.

So, how and why did ASCAP Start? [4] At the

end of the 19th Century, in the United States,

the owners of music copyrights, called "music

publishers” (because they printed sheet music

containing versions of their songs), were having

a hard time fighting people who counterfeited

their sheet music. In 1889, the US Copyright

Act was amended to provide for the payment of

royalties for the performance of music. It was

seen as a way to protect music publishers from

counterfeit sheet music because it focused on

the value of the performance of the music, not

just its worth on the printed page. But it was

only a law in concept as there was no real way

to enforce it. Yet.

In New York City, which was then the centre

of the North American music business,

the Witmark boys – a five-brother team of

songwriters, music printers and publicists - had

built themselves into one the leading music

publishing companies in the USA. They and

several other music publishers came together in

February 1914 to form the American Society of

Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP).

Their purpose was to issue licenses and collect

royalties from those who performed music in

public. This was the new stream of income,

separate from the other monies that could be

earned from owning songs.

They based their model on a European system

where cabarets, night clubs and other public

venues were required to pay a fee for a license

that allowed those places to play the music

publishers’ music in their venues. After

deducting an operating fee, the organization

would then distribute collected royalties directly

to member

publishers and

composers. Their

key to success

was to enlist the

participation of

all venues from

the smallest to the

largest. This was

a time-consuming

project and an

area where much

energy was

expended.

|

|

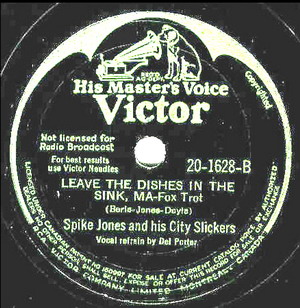

This early 1940s Victor label clearly

asserts that the recording was "Not Licensed for Radio Broadcast"

|

|

|

As the years went

on, however,

there was a

technological

development happening that would take up

even more of their time and energy. The dawn

of radio and programs that played music on the

radio posed a new set of problems for ASCAP

in the 1920s. The station owners/broadcasters

simply refused to pay ASCAP in order to

play their members’ music. The broadcasters

believed that, once they had purchased the

record, they were free to play it all they wanted

because they owned the physical copy. The

broadcasters also believed that the fee ASCAP

sought was too high.

This battle raged through the twenties and

in to the late 1930s with the broadcasters

successfully rebuffing ASCAP’s attempts to get

money out of them. ASCAP finally issued a

threat to the broadcasters: pay us for using our

music or stop playing our music altogether.

The broadcasters responded by forming their

own performing rights organization, "BMI”, in

1939. BMI then agreed with the broadcasters

on a rate for the performance of its music on

radio. Now BMI had to acquire some content.

Because ASCAP controlled the great majority

of American popular music, BMI was forced to

look to the musical fringes for its members.

To better understand what was going on at

the time, it’s important to know that ASCAP

represented songwriters like Cole Porter, George Gershwin

and Irving Berlin.

They considered

their writers

to be the true

representatives of

America’s music

and therefore

"society’s”

rightful "popular”

music. ASCAP

basically ignored

all the music that

"society” associated with the unsophisticated

classes and "degenerates”. They made it very

hard for jazzmen, country fiddlers, Appalachian

musicians and blues singers to obtain

membership in their organization.

With the formation of BMI, because the new

organization needed music for broadcast

purposes, they opened their doors to a wider

selection of musicians.

As a result of the broadcasters forming BMI,

ASCAP went ballistic and announced that as of

December 31, 1940, they would press charges

against any radio station that broadcast ASCAPlicensed

music without paying the licensing

fee. The penalty for copyright infringement for

failing to pay royalties at that time was $250 for

each time a song was played.

The broadcasters responded, as one would

expect: they simply revised their play-lists to

include only BMI-licensed songs. Overnight,

all the George Gershwin, Hoagy Carmichael

and Harry Warren songs vanished from the

airwaves. And what happened?

Nothing. The broadcasters discovered that

the American radio-listening public had no

problem with the new content and there was

no decline in the audience. So with continuing

revenues based on the revised play-lists, the

broadcasters continued to invest in BMI. BMI

offered equitable, fair contracts to interested

songwriters. They made it easy to join, as they

did not require that a songwriter already have

published at least 5 songs, as ASCAP did.

At the same time, other dramatic events were

unfolding. In the summer of 1940, a suit was

instigated by the U.S. Justice Department

that accused ASCAP of restraint of trade,

monopolistic tactics, and discrimination against

non-members. It was this suit that finally

succeeded in bringing ASCAP to its negotiating

knees. Twenty-six years of doing battle with

station owners had drained the organization’s

finances and had broken its morale. Finally, in

November 1941, the organization was forced

to settle for the same two and three-fourths

percent of the radio stations’ annual advertising

revenues, a proportion that the stations had

willingly given BMI, far below the seven and a

half percent that ASCAP had always demanded

but had never received.

|

|

James Petrillo

|

|

|

There were those who saw in the settlement

a major victory for ASCAP, which had never

before earned so much as one cent in broadcast

royalties. Others saw it as a pyrrhic victory, for

ASCAP’s hard line of negotiation had brought

about the existence of BMI, whose roster of

talent signalled to many the beginning of the

end of the commercial music business’s (Tin

Pan Alley’s) golden era.

Yet, this is not the end of the story, as there

arose some unintended repercussions. The

radio broadcast industry initially provided a lot

of jobs for live musicians to play in the radio

shows. The settlement between the broadcasters

and ASCAP now meant that radio had a lot

of pre-recorded content to choose from. Prerecorded

content was less expensive to air but

meant fewer opportunities for live musicians

to play. This rankled the powerful musicians

union, the American Federation of Musicians,

to no end. And so, in 1942, James Petrillo,

the president of the AFM, called a strike and

pulled the Federation’s musicians out of all

recording studios to prevent the manufacture

of new records. Petrillo had been looking for a

way to break the back of the recording industry

for some time and this settlement with the

broadcasters pushed him to draw the line in the

sand.

On August 1, 1942, the strike went into effect

and effectively halted the manufacture of any

new records. Because of this, many blues, folk

and jazz musicians (who would more than likely

have been BMI members) were prevented from

recording. ASCAP publishers, however, had a

banner year in 1943 because record companies

had a huge backlog of unsold disks containing

ASCAP-licensed songs that they re-released

during the strike.

This was a short-term problem, however. By

the mid-1950s, 80 percent of all music played

on the radio was licensed by BMI. But the

tale of music in North America after WWII is

another story for another day.

And what of these performance rights societies?

ASCAP and BMI are big business still

today and luckily the restrictive membership

application practices have disappeared.

Footnotes

Silvester, Peter: A Left Hand Like God: The

Story of Boogie Woogie. London: Omnibus

Press 1990 at 165 to 166

- Coleman, Mark. Playback – From the

Victrola to MP3, 100 Years of Music, Machines,

and Money. Cambridge: Da Capo Press. 2003

at 46

- Coleman, Rick: Blue Monday – Fats

Domino and Lost Dawn of Rock ‘n’ Roll.

United States: Da Capo Press 2006 at 3 to 4.

- The bulk of the story from this point

forward comes from media business author

Marc Eliot’s fascinating book "Rockonomics".

Eliot, Mark: Rockonomics – The Money

Behind The Music. New York: Citadel Press,

1989

|