|

The History of Berliner Gramophones

Part One

by Mark Caruana-Dingli

The following article, printed in several parts

over the next few issues, will focus on the

contributions made by Emile Berliner who

helped usher in the era of recorded sound. His

move to Canada early in this industry's history is

not well documented, even though his contributions

continued on for many years after leaving the

United States. This will be discussed in detail in

the latter part of this article. I would like to thank

Oliver Berliner (Emile's Grandson and CAPS

member) for his assistance with this article and for

contributing information.

The History of Recorded Sound

Credited with the first successful reproduction of

sound, Thomas Alva Edison was not the first to

propose that a method of reproducing sound was

possible. French inventor Charles Cros had

predicted that after sound waves were etched onto a

glass disk, a copy of the track could be made in a

metal plate and used to recreate the original sounds.

The engraving process was not new, and had been

successfully used in a device called the

Phonautograph built by Leon Scott de Martinville

in 1856. Cros' idea was that sounds could be

reproduced from these etchings. This idea had not

been tested by him as he was unable to obtain the

financial backing needed for his experiments.

At about the same time, Thomas Edison was

conducting his own experiments based on a similar

idea. In 1877 he was successful in impressing the

sound waves into a tinfoil sheet wrapped around a

rotating drum, and is credited with inventing the tin

foil phonograph, a device able to record and

reproduce sound. As Edison's attention was shifted

from this device for a period of time to concentrate

on his electric light bulb experiments, it was left to

others to continue experimenting with this exciting

discovery.

In 1880, Alexander Graham Bell, having just

received the Volta Prize from the French

government, was looking to invest in a new project

and had felt that Edison's tin foil phonograph had

potential. Enlisting his cousin, physicist Chichester

Bell and modelmaker Charles Sumner Tainter,

experiments were conducted leading to many

improvements to the phonograph. Unlike the tin

foil method which resulted in a recording which

could not be replayed more than a few times with

any success, Bell's research yielded a machine

which was capable of a relatively

permanent recording on a wax coated 6 inch long removable

cylinder. To manufacture and distribute this

machine and subsequent models

of it, The American Graphophone Company was founded in

1887. This company, which eventually consolidated

with The Columbia Phonograph Company, was to

be the source of bitter court battles for the father of

the disc record, Emile Berliner. Up to this point the

techniques used to record and reproduce sound

incorporated a groove being etched or indented

vertically into the surface, which was in contrast to

the side to side lateral motion of the etched sound

wave, which had been proposed by Cros and used

by Leon Scott.

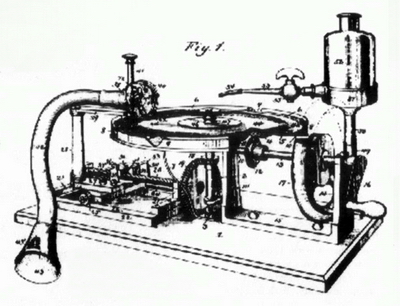

Part of Berliner's Canadian Gramophone Patent

No. 55079 from 1895

|

|

The Disc Gramophone

The history of the disc record gramophone begins

with the Berliner Gramophone Company's

founder, the German born Emile Berliner

(1851-1929) who immigrated to the United

States in 1870. Settling in New York,

Berliner worked several jobs in

his early days while he

taught himself about

electricity and acoustics.

After moving to Washington,

Berliner began to experiment in a

small lab he built in his

apartment. His interests

led him to work on an

improvement to Alexander Graham

Bell's newly invented

telephone, which could benefit from

improvements to the transmitter to make

it a viable product. Berliner's experiments resulted in a practical

transmitter for which he applied for a patent on

June 4th 1877. Berliner then sold this patent in

1878 to Bell for $100,000 and was retained as a

consultant by the company. After a 2-year leave of

absence in Hanover, Germany where he had set up

the Telephon-Fabrik Berliner to manufacture

telephone equipment, Berliner returned to the US in

1883 where he resigned from Bell and immediately

set up a lab in Washington to work on new research

into recorded sound.

Berliner experimented with recording an undulating

wave onto a rotating disc, an idea that Cros was

unsuccessful in financing earlier. This new device

for recording received a patent in 1887 and was

first presented at the Franklin Institute of

Philadelphia on May 16th, 1888. After solving the

problem of creating a master from which other

copies could be pressed, Berliner went to Germany

and sold his idea to the Kammer und Reinhardt toy

company which marketed his invention for the next

4 years as a toy that played 5 inch vulcanized

rubber or celluloid discs. Although of poor quality,

these early discs, which were made by Berliner in

the US and played at a speed of about 90

revolutions per minute, were easy and cheap to

mass-produce. This advantage, which would

eventually result in the demise of the cylinder

recording is considered Berliner's greatest

contribution.

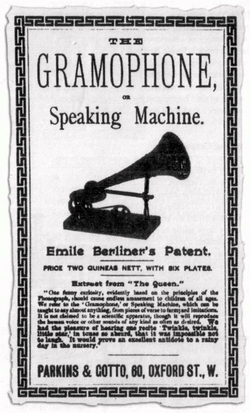

An early ad from Britain

|

|

In 1889, after having modest success in Germany,

Berliner began pursuing entry into the

American marketplace with a new hand-driven

gramophone that played larger 7”

discs. In order to make his gramophone

attractive to investors, Berliner opened up

a retail store in Baltimore late in 1894 to

market his hand driven machines and their

7-inch celluloid discs.

In 1895, after several failed attempts to raise sufficient

capital, Emile Berliner founded the

Berliner Gramophone Company to control

the manufacture and sale of gramophones

and records. The royalties from these sales

would be paid to Berliner's patent holding

company, the United States Gramophone

Company.

Unfortunately, Berliner's early forays into

the talking machine market met with

limited success, as a hand driven

mechanism was more of a novelty when

compared with the more sophisticated

Edison or Columbia products of the period.

What was needed was a spring motor to

give his invention a chance to make

headway in a market that was showing

signs of great potential. After

unsatisfactory attempts by other

subcontractors, Berliner's problem was

solved by a New Jersey machine shop

owner named Eldridge R. Johnson who,

after initially being contracted to

manufacture a crude motor, designed a

proper working motor that became the

basis of the most recognized talking

machine in history. With the introduction

of the "Improved Gramophone" in 1897, Berliner

was finally ready to make a significant dent in the

talking machine market.

Marketing of the new machines was to be handled

by the National Gramophone Company set up by

Frank Seaman to promote and sell Berliner's

products. Under this arrangement Berliner neither

built nor marketed the Gramophone, but as the

patent holder he made his profit by buying from

Johnson and selling to Seaman. With Seaman's

aggressive marketing style and the "Improved

Gramophone" of 1897, sales were off to an

impressive start.

In 1898, the Columbia/Graphophone group, seeing

the likelihood of a competing technology, launched

a patent suit against Berliner's and Seaman's

respective companies for marketing a product

which they felt infringed on their patents.

Columbia's strategy was to go after the marketing

company along with the patent holder in hopes of

getting an injunction to disrupt the sales of

Gramophones long enough to allow them to enter

the disc market with their own product. The suit

itself had little validity and would eventually be

settled in favor of Berliner, but in the interim, the

pending injunction was to cause many problems for

Berliner.

A Kammer und Reinhardt toy gramophone

|

|

Already disenchanted with his

financial arrangement with

Berliner, Seaman decided to

protect himself by forming the

Universal Talking Machine

Company and began

building a new line of

machines, the

Zonophone, that he

attempted to market under

the Berliner patents. Berliner, who

liked the present arrangement which forced

Seaman to buy machines only from Johnson, with

a hefty Berliner markup, refused to consider any

changes. The rebuffed Seaman began to stockpile

his new line, and when he had sufficient quantities

ceased his orders for Berliner's Gramophones.

This created a major problem for both Berliner

and Johnson who had no experience or facilities to

market or distribute their product.

Seaman's next move was to accept in 1900 a

consent decree in court admitting infringement of

Columbia's patents and thus the court granted

Columbia a permanent injunction, making it illegal

for Berliner and Johnson to sell their products. The

crafty and ever manipulative Seaman then

proceeded to make a deal with Columbia, which

allowed him to sell his Zonophones under the

protection of Columbia's patents. This turn of

events was most serious for Johnson who had a

large stockpile of machines, and had just completed

a new manufacturing plant for which he was

$50,000 in debt. In order to get back into the

business Johnson established a new company under

the name The Consolidated Talking Machine

Company and began marketing his machine. An

injunction was obtained against Johnson but he

succeeded in having it lifted and sales then

progressed beautifully. Eventually Berliner and

Johnson prevailed in the courts and a deal was

struck with Berliner so that Johnson would take

ownership of the patents. In October, 1901, The

Victor Talking Machine Company was founded by

Johnson to hold these valuable patents. The

company was named "Victor" to celebrate the

Berliner court "Victory".

|