|

Edison Class M’s Unique Place in Canadian Phonographic History

by Paul Dodington

It was in the year 1961 that I was a participant in an

antique car tour from London to Brighton,

Ontario. Antique cars and boats have always been

my "summertime" passion, while antique phonograph

and record collecting seemed to be most appropriate

activities for "those long, cold, dark, shivery evenings

when your health and convenience compel you to stay

indoors," as an early phonograph ad stated.

One of the scheduled stops on that London-

Brighton tour was historic Barnum House, near the village of Grafton, Ontario. Staffed largely by volunteers,

Barnum House presented a wonderfully eclectic mixture

of historic artifacts so typical of small country museums.

The second storey of the building was rather less organized than the main floor, and it was in this area that all manner of strange and unusual items were to be found. It was apparent that most

of the articles upstairs were

unidentified, or perhaps things that did not fit neatly

into the well-organized display areas on the main floor.

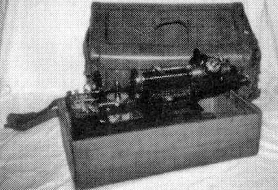

Fig. I - Edison Class M phonograph with original

tooled leather case

|

|

While poking about this jumbled array of miscellany,

I chanced to see an ornate leather carrying case and

wooden box underneath a table. Further investigation

revealed a strange-looking phonographic device in the

case (Fig. I), and about 48 mint brown wax cylinders in

the box (Fig. II). The machine bore some resemblance to

an Edison Triumph phonograph, but did not appear to

have the Thomas A. Edison trade mark anywhere. I concluded that it must be some kind of dictating machine,

of minimal interest, so I replaced the lids and rejoined

the car tour for the next leg of the journey.

About five years later,

I visited Barnum House and

saw the machine again, under similar circumstances, but

noted that almost half of the wax cylinders had been broken. But this time, I took notes of the information on a

nickelled plate attached to the bedplate of the machine

and left, determined to find out more about it.

Now, it is essential to understand that we phonograph buffs 25 or 30 years ago did not have at our disposal the wealth

of research and reprinted material that

exists today, material which makes it rather a simple matter to identify even the most obscure phonograph. Of

course, we all had Roland Gelatt’s book, "The Fabulous

Phonograph", and the subsequent "Tin Foil to Stereo",

but beyond these and a few Edison reprints available

from the City of London Phonograph and Gramophone

Society, there was precious little to go by.

I eventually began to realize that this machine bore

an uncanny resemblance to Edison's "Perfected" phonograph, the one shown in the famous picture of the

bleary-eyed Edison taken at 5:30 a.m. on June 16 1888

after an intensive period of work on the playback

machine. I was on to something.

Long after Barnum House had been closed down

for the season, I awoke the curator from her long winter’s nap and discovered not only that the museum had

accepted the phonograph and cylinders on loan, but that

the staff really didn’t have any idea what to do with them

anyway. It was suggested that I would probably be doing

the museum a great favour if I could make arrangements

to purchase the machine from its owner, and then

remove it from the already overcrowded building.

Some hours later, in the midst of a December blizzard, I knocked on the door of a lovely Victorian home

in Warkworth, Ontario, where I met Miss Nell Ewing,

the octogenarian owner of the machine. The dear old

soul seemed to be convinced that I must be a burglar or

at the very least, a confidence man, but luckily her

nephew happened to be visiting and with his help, I was

able to negotiate a fair sale price for the phonograph and

cylinders which she had loaned to the museum many

years before, just to be rid of them.

I presented the bill

of sale to the museum curator

next day, and took delivery of my new "find". Upon my

return home, I discovered that in addition to the phonographic items, I had purchased several thousand hibernating houseflies, all of which escaped from the bowels

of the machine as soon as it was exposed to a heated

room. The next day was spent, alas, not tinkering with

the new toy, but swatting flies, whose numbers had by

this time assumed mammoth proportions not unlike the

locust plagues of Biblical fame.

Identification of Machine and Cylinders

Then the quest for proper identification of the machine

and cylinders began in earnest.

Photographs were taken,

a description prepared, and letters of inquiry were sent

out to several collectors whom I thought might be able

to shed some light on the matter. Nobody seemed to

know what the machine was. Even Professor Walter

Welch at Syracuse University had never seen anything

quite like it before. Such was the state of phonographic

knowledge in 1966.

Meanwhile, I set to work on the machine itself to

see if it could be made to operate. The North American

Class M is driven by a 2 1/2 volt D.C. electric motor and

it was evident that some previous tinkerer had hooked it

up to 110 volts A.c. and had fried off all the soldered

connections on the commutator. Beyond this, everything looked in pristine condition. Even the 75-year-old

leather drive belts were in excellent condition, and they

still remain so today after more than 100 years of service.

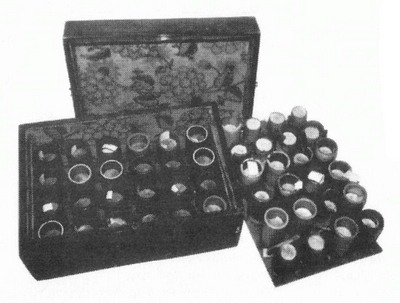

Fig. II - Original 48 brown and white wax cylinders,

dating 1890 to 1893, which came with the

Edison phonograph

|

|

In less than a week, the machine was operational

and I began to play the 30-odd surviving cylinders, all of

which appeared to be of 1890 to 1893 vintage. It was a

most awesome experience to be enabled to hear sounds

from the very dawn of phonographic history, reproduced just as clearly as they were three quarters of a century before. Eventually, I was to discover that whereas most of the cylinders or "phonograms" were of commercial U.S. origin, there were several others which were

contemporary Canadian recordings, undoubtedly

recorded on the same machine.

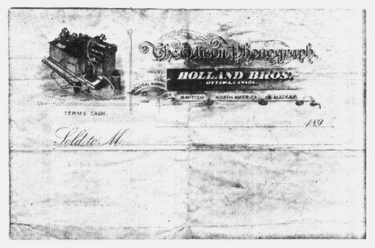

The existence of these Canadian cylinders, along

with a number of tickets found inside the cabinet drawer saying, "Admit One to Phonograph"

(Fig. III), led to the conjecture that in the beginning the machine was probably used as a demonstrator. A bill of sale found inside the

case (Fig. IV), dated January 21st 1892 indicates that

1 dozen No. 1 blanks were shipped to W.

A. Holmes of Warkworth, Ontario, at the cost

of $4.00 plus 25 cents packing and return

charges. An early typewritten list of record titles

found in the drawer bears evidence that there

must have been considerably more cylinders

with the machine at one time than now exist.

Some of the earliest cylinders (1890-91) have

spoken announcements which give the actual recording

dates. Some others have thin printed paper titles glued

into a shallow groove on one end, naming the title and

artist. These appear to have originated in the Orange

New Jersey studios.

W. A. Holmes was apparently Miss Ewing's grandfather. Unfortunately, she was failing mentally, and was

not able to supply any relevant information about him

or his reasons for having purchased the outfit in the first

place. Nevertheless, considerable evidence exists, both

with the equipment and elsewhere, which has formed

the basis for a probable scenario.

The machine itself is a Class M (the "M" indicates

a battery-powered motor-driven model) built by the

Edison Phonograph Works for the North American

Phonograph Company, Jesse Lippincott’s patent-holding

and sales trust established in 1888 to exploit both the

Edison and Bell-Tainter patents and machines.

Lippincott licensed a series of territorial agents throughout the North American continent, and in turn these

agents leased phonographs and gramophones in much

the same way as Bell leases telephones and equipment

today. One of the notable agencies was located in the

lucrative territory of the District of Columbia, and this

organization survives to the present day as CBS.

The general agents for the territory of British

North America and Alaska (remember that the

Dominion of Canada at the time comprised only a portion of British North America) were Holland Bros. of

Ottawa. This was an agency of parliamentary reporters,

so it is understandable that they could foresee a bright

future for the phonograph in their field. (They subsequently became involved in the Canadian promotion of early motion picture equipment.)

Fig. III - Yellow cardboard admission ticker indicates that the Class

M may have been originally used as a demonstrator

|

|

Whereas the U.S. agencies promoted the use of

phonographic equipment on a lease basis, this idea must

have been judged unworkable in Holland Bros. territory

due to its geographic vastness. Thus the machines were

sold outright to customers, a happy circumstance as it

turned out because Holland Bros. did not recall their

equipment to be scrapped upon the collapse of North

American in 1893 as was the fate of many of the leased

U.S. machines. This accounts for the comparative rarity

of North American machines today and also accounts

for the existence of the Edison "Victor" and "Balmoral"

machines of a decade or so later — machines that were

undoubtedly built largely of parts salvaged by Edison

from the assets of the defunct North American

Phonograph Company.

The earliest Edison machines available from North

American in 1889 were known as the "Spectacle"

phonographs, due to the peculiar arrangement

of the

separate recorder and reproducer on a swivel bracket

developed by Ezra Gilliland in 1887-88. By 1890, this

device had been simplified considerably by the consolidation

of the recording and reproducing styli onto the

same "standard speaker", as it was then termed. The

speaker can be easily changed from recording to play-

back mode by simply revolving the unit about 30

degrees one way or the other within its carriage by

means of a hand lever. This lever continued on for many

years in the reproducers and recorders of later Edison

phonographs as a useless appendage long after its original function had ceased to exist.

The phonograph is identical to the one detailed in

the Holland Bros.bill of sale with one exception: where

a large cast iron "pause" bracket is screwed to the cabinet

base in the engraving, this machine has a nickelled plate

stating: "Holland Bros. Ottawa, Ontario, Solo Agents

for Canada". The location and size of this plate suggest

that, as was the case with all the other agencies by 1891,

Holland Bros. had become fully aware of the dismal failure of the phonograph as a practical piece of office equipment, but that its salvation rested undoubtedly in its promotion as an entertainment device, hence the

removal of the "pause" brackets.

According to the report of the 1890 Convention of

local phonograph companies,it was already becoming

obvious that the only road to commercial success

of the whole North American phonographic venture lay in the

vigorous promotion of phonographs in the field of

musical entertainment, and as a corollary, good quality

pre-recorded musical cylinders would have to be made

available in much the same way as pre-recorded VCR

tapes are available today. This evidently would create an

ideal situation for the business: individual local promoters could be enticed into a purchase or lease arrangement whereby they could give "demonstrations" or

"phonograph concerts"as a sort of travelling road show.

Perhaps Mr. Holmes used his phonograph in this way.

The existence of a few Canadian-made cylinders in

the group is tantalizing testimony as to what kind of historic material was lost through breakage during that 5-year period in Barnum House. With all due respect to the efforts of the curator and staff of Barnum House,

this accidental destruction of historic artifacts serves to

emphasize that esoteric equipment of this type often

stands a far greater chance of long-term survival in the

hands of an interested private collector than in even the

best-intentioned institution.

The Machine’s Features

The "standard speaker" or combined recording/reproducing head is unlike the later "Automatic" and Model

C reproducers in that it contains no provision for any

lateral runout of the record grooves in playback mode.

This peculiarity requires the listener to constantly adjust

or "tune in" the sound, much as one would tune a radio,

by adjusting a knurled thumbscrew, which in turn

slightly alters the position of the stylus vis-a-vis the

record groove. If you neglect to make this adjustment,

it is quite possible to play an entire cylinder without

hearing the slightest sound, due to the stylus' travelling

the land between two adjacent grooves, rather than in

the groove itself. The introduction of the "automatic"

speaker in 1893 must have been a welcome improvement.

Fig. IV - Faded with age, the bill of sale reads: "Ottawa, Jan. 21st

1892. Sold to W. A. Holmes, Warkworth, Ont. To 1 Dozen No. 1 Blanks $4. Packing .25 cents. C.0.D. $4.25 and

return charges."

|

|

The most unique identifying feature of the Class

M and Class E phonographs is the vertically-mounted

flyball governor just to the left of the machine. This

governor, which looks very similar to that found on any

ordinary spring-wound phonograph or gramophone, is

actually very different in function. Whereas both types

of governor are really modifications of the James Watt

steam engine flyball governor of earlier times, the adaptation found on the Class M and E machines is, in my estimation, the most creative.

The electricity to drive the Class M was supplied

originally by a choice of Grenet cell, Primary Edison

Lalande Battery, or Primary Chromic Acid Battery. Due

to the high cost and relative inefficiency of such batteries, it was imperative to design an efficient governor

which would conserve battery current as much as possible. At the same time, however, the designer of the

governor was faced with the reality of a very heavy electrical load upon start-up, a load so great that it would

preclude the use of anything of a delicate nature in the

governor mechanism.

This anomaly was solved in a most ingenious fashion. Upon closing the main motor switch, the large proportion of the current is made to pass directly through a "shunt" or by-pass circuit, thus avoiding the delicate

governor. However, the current supplied through the

shunt is only about 80% of the value required to bring

the machine up to its full operating speed of 120 rpm.

The remaining 20% passes through the governor.

Whereas in the usual gramophone governor the centrifugal expansion

of the flyballs engages a collar against

a friction pad to limit speed, this governor functions

exactly the opposite: the electrical current which passes

through a brush to the collar is gradually reduced as the

rpm increases, thus increasing the electrical resistance of

the circuit and limiting the current supplied to drive the

motor. Speed changes may be made by a vernier adjustment which moves the brush into tighter or looser contact with the collar, thereby varying the electrical

resistance at a given speed. This governor is thus a current regulator and in actual operation it works quite

acceptably, although it is a lot more delicate and sensitive to adjust than the familiar spring motor governor.

Accessories that appear to be original with the Class

M machine are as follows: spare drive and governor

belts, camel's hair brush for removing wax shavings from

cylinders, a small camel's hair brush for cleaning the

styli, extra listening tube ends, speaking tube, spare

French glass diaphragms and spare motor and governor

brushes. It is a tribute to the quality of design and workmanship found in this machine that it has not been necessary in its first century of operation to make use of any of the spare parts. They are still brand new. If only

today’s audio equipment could be as long lasting! Such is

the price of progress.

Over the past quarter century the Class M has been

featured in countless displays and lectures, but two in

particular stand out in my memory as unique. The first

was upon the occasion of the opening of the 1975 exhibition, "85 Years of Canadian Recorded Sound"at the

National Library in Ottawa.

I was asked by my dear friend Ed Moogk to have the machine operable in order

to re-enact, after a fashion, the occasion of the recording

of the voice of Governor-General Baron Stanley of

Preston at the Toronto Industrial Exhibition on

September 11, 1888. This time, though, Governor-General Jules Léger was to make the Vice-Regal cylinder

which would then be deposited in the National Library.

Unfortunately, His Excellency was stricken with a

paralysing stroke shortly before the opening of the

Exhibition, and regretted having to decline the invitation to make the historic recording due to the extreme

difficulty he was experiencing with speech. However, a

cylinder was made of the voices of some lesser dignitaries

and thus the occasion was captured permanently in wax.

The other occasion that stands out was in 1988 at

the CNE in Toronto when the machine was featured in a

display organized by John Rutherford and other cars

members. This display commemorated the 100th

anniversary of the making of the Governor-General’s

legendary cylinder at the same location on a similar

machine.

It is to be hoped that fate will be kind enough to

permit this unique piece of Canadian history to continue to survive and function for a very long time in the hands

of careful and concerned owners, or should I say

custodians, and that it may be as interesting and relevant

in the lives of future generations of Canadians as it has

been in mine.

|