|

The Canadian Connection: Brunswick

by Brian Boyd

Brian Boyd, discographer

|

|

This is the first in a series of articles authored by

the late Brian Boyd. a well-known and respected collector and discographer, and a member of CAPS.

Brian,

who died on February 26th 1991,

built up over many

years an extensive collection of

"personality" records,

mostly of popular vocalists of the 1920's and 30's. He

was a regular speaker at CAP meetings.

Brian

Boyd dictated

the

following

in

January

1991

from

memory

alone,

without referring to his

records

nor

to his

books.

He

stressed that

some

of

the

statements are

based,

not

on

positive proof, but on the evidence

that

he

had

built

up

over

many

years of astute observation of the

physical

records.

He

was

anxious

that

the

reader

understand

that

what

follows is not

a definitive

history. Rather,

he hoped that this

article

would

arouse interest

and

foster

research

so

that

the

definitive history could be written

by others.

The

American

Brunswick-Balke-Collender

Company used Canada to test-market the production,

distribution

and

sale

of

their

phonograph

recordings.

This

seems to

have

occurred

between

1916 and

1920.

Most of us

have

seen

those

fabulous

green

and

gold

labels that

were

used. it

was

a vertical-cut

record.

The

patent situation

had

not

cleared

up

and

they

were

unable to

make

lateral-cut

records,

which

were controlled

by

Columbia

and by Victor.

The

Brunswick

verticals

appear

in

a

5000

series.

They

don't

appear to

be Canadian

recordings - that

is, recordings by

Canadian

artists.

I believe

some

work

has

been

done

to try to trace the source of

them,

and it

may

be

a company like Pathe or

one of the

other

smaller

American

companies

that

supplied pressings for sale in Canada.

Around

1920

the patent situation

was resolved

in

favor of the

non

Victor-Columbia

interests,

and

everybody

was

able

to

produce

lateral-cut records.

At that point

Brunswick

abandoned

its

attempt

in

Canada

to

market

a

vertical-cut

record and began to make

lateral-cut records that

could

be

played

on

a

standard phonograph.

The

standard

Brunswick

record

was

introduced

in

1920

simultaneously, or almost so,

in Canada and the U.S.A.,

and that

may

give

an

approximate date for

the

establishment

of

a

Toronto

pressing

facility.

I

believe

the

green-label

Brunswicks

had not been pressed

in Canada.

The

black-label

ten-inch

records

were

a

standard

popular

series,

much

like

the

black-label

ten-inch

Victors.

They started

at the

number

2000,

or

perhaps

2001,

and

ran right up into the 4000s

and

6000s with

a gap for the 5000s.

The

5000s

had been

a

series

for

premier artists

such

as

Isham

Jones

in

the

early

twenties.

They

had

a

purple

label

instead of the black,

and had

all

the characteristics

of those acoustic

Brunswick

labels that we've seen so often.

In

terms

of

the

corporate

continuity

of

Brunswick

in

Canada,

it

continued

in

one

form or

another as,

what

I

would call,

an

independent

company.

Of

course,

It

was

a

subsidiary of

the

American

Brunswick-

Balke-Collender

Company

— only one of

many

subsidiaries

because

Brunswick

continued to

make

pool

tables

and

phonograph

cabinets

both under contract for other companies and

under their

own name.

So the music division

was

a

separate

entity

from

some

of

the

Brunswick-Balke-Collender

Company's

other

activities.

It

continued

to

produce

records.

I

don't

know

if it recorded

much

in Toronto,

but it

recorded

occasionally

around

Montreal.

There is evidence that the Jack

Denny Orchestra,

which

was popular

in one of the

Montreal hotels,

made

some

of its records

in

1928

-

tunes

like

"Hello,

Montreal"

on

Brunswick

3884 -

in

Plattsburg

which

was

right over the border

and very accessible to

Montreal.

Possibly there were

union

problems

that might dictate

a location

in the United

States

instead of

Canada,

especially if the

particular

orchestra

was

augmented

with

musicians

from

New

York.

There are several

masters that

show

up

with

a

PB prefix,

and

Brunswick

had

a habit of

using

the

location

for

the letter prefix to the

actual

master

number.

So

you

had

KC

for

Kansas

City,

C for Chicago

and

so on.

The Canadian

labels

were

printed

in

Canada

and

identified

"Made

in

Canada".

There's

absolutely

no difficulty

at all, at least

from the time of the

introduction

of

the

1920

lateral-cut

record,

in

distinguishing

a

Canadian

pressing.

Everything

about it

makes it

obvious that

it's Canadian

and not an

American pressing,

unlike

Columbia

where the

information

is

a

little

harder

to

decipher.

The

mere

fact

that it

says

"Made

in

Canada"

is

obviously

the critical point.

There are

some interesting things with the

labels

in the early electrical

period.

Many

collectors

will

have seen

the little

tag

"Light-Ray

Electrical

Recording"

on

the

label

of

a

circa-1926

Brunswick.

That

note

was

on the

Canadian

label

in the upper-left

position just around the level of or slightly

higher

than

the

spindle

hole. It also

showed on west-coast American pressings, but

the east-coast American pressings never used

"Light-Ray

Electrical

Recording".

I'm

not

sure why.

I'm fairly certain that I've never

seen

an

east-coast

American

pressing

with

"Light-Ray

Electrical

Recording"

on

the

label.

An interesting thing about the Canadian and

west-coast American pressings that

show the

legend

on

the

label

is

that

there's

a

slightly different

period

when it appears.

I can't

remember if the Canadian pressings

show it earlier

and

end earlier,

or vice

versa.

But the introduction of that

legend

and then its

disappearance

vary slightly in

in time

between the two

countries.

The Canadian

version,

I believe,

does

not

abbreviate

"Light-Ray

Electrical

Recording".

The

American

ones

use "Elec." for "Electrical

and

"Rec."

for

I

guess

just

because

of

the

space requirements.

That was Brunswick's

famous touted electrical

recording

system

which

had

been

developed

somewhat

independently

from

the

Western

Electric

process

which

Victor

and

Columbia

had joint interest in. It

was

not

a

very

good electrical

system,

and

had to

pay the exorbitant royalties that Columbia

and

Victor

always

charged

for

access

to

those patents.

From

my

perspective

Brunswick

was

a city

label.

They

had

sophisticated

artists

in

their

vocal

catalog

—

people

like

Libby

Holman, Belle Baker,

and so on. They had Al

Jolson,

the world's greatest entertainer.

They had Harry

Richman. These were the cafe

favourites,

the people

who were big

in

New

York

but probably

had

a relatively

limited

appeal

in the smaller

urban centres

in the

U.S.A.

They

also

had

a strong Los Angeles

component,

and

in

the

twenties

Brunswick

did quite

a

lot of recording

on the west

coast.

They

had

a

west-coast

pressing

facility,

certainly

as of

about

1924/1925.

There's

a

wonderful

photo

in

a

book I've

seen of

Al

Jolson

holding

a pressing that's

just

come off

one of the Los

Angeles

pressings.

All

of the

majors

established

west-coast pressing facilities

in the early to

mid-twenties

because

shipping

costs

were

just so high.

By that time there was

a sufficient population on the west coast that it

made

more

sense to

send

a

metal

part

for

stamping

purposes out to the west coast and

press

the

records

there,

saving

a

very

considerable

amount of

shipping cost across

a

largely

unpopulated

middle

of

the

continent.

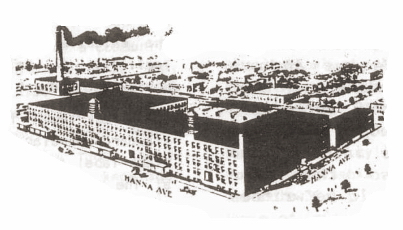

Brunswick Factory, Hanna Avenue, Toronto, 1921

|

|

Brunswick did quite a lot of recording on the

west

coast.

They

also

had

a

pressing

facility

in the

Chicago area

and one

in

New

York.

I

have

no

proof

of this other

than

differences

in pressing characteristics.

It

seems

to

me

quite

evident

from

physical

evidence

that

Brunswick

had

at

least

two

pressing facilities

by the middle twenties,

and three later

on

in the twenties.

It

may

be that the Vocalion works were one of those

facilities.

I think it's Muskegon, Michigan,

that

was

the factory

location

in the mid-west.

Although

I call it a

New York or city label,

Brunswick's

headquarters

were

in

Chicago

as

a

company,

and

they

always

maintained

a

business

address

in

Chicago.

For

example,

the

Brunswick Brevities radio pressings that

were

made to advertise

Brunswick records and

products

in the

late twenties

identify the

Brunswick-Balke-Collender

Company

of

Chicago,

Illinois.

So that

was definitely

their

corporate

headquarters,

probably

for

all of their operations

including the

music

division.

Brunswick

was

a slightly

anomalous

company.

It

had

subsidiaries

all

over the

world -

Argentina,

Germany,

France,

perhaps

other

eastern

European

countries,

Britain of course

where it started out using the Chappell

company's

Cliftophone

label

as

the

Brunswick

label

in Britain,

and

Canada.

It's

a gold

mine of interesting information.

Multiple

takes

were

a

phenomenon

on

Brunswick,

surprising

for

a

major

label.

I

have

one recording

in which the English issue uses

one take, the American west-coast issue uses

another,

and

the

American

east-coast

uses

a third take,

while the Canadian issue

uses

one

of

the

two

American

takes.

So

there's three takes

of

one

side,

and

with

evidence of differences that are indisputable

in the rendition of the song. It's almost as

if the two singers,

who are Esther

Walker and

Ed Smalle, are rehearsing

in the earlier

two

takes

and finally

come

up with

a definitive

version

in

the third take.

But,

of course,

because

we don't

have the master

numbers

we

can't actually

put them

in exact sequence of

recording.

But that

was

so typical

of

Brunswick.

In the

late twenties there would

even

be

separate

versions

of the

same title.

On

Brunswick

4873, "If

I

Could

Be With

You"

and

"Little

White

Lies"

by

Marion

Harris,

there

are two separate recordings

made at different

times

with different

master

numbers of both

sides of the record. If

you hunt hard enough

you

can find these different versions issued

under the

same catalog

number

and noticeably

different, at least to a tuned ear.

The

same

occurred

with

some of the

Hal

Kemp

sides.

For

the first

four

sides

on

which

Bunny Berigan

appears,

there are two takes of

each.

I

have

them

and

they

are

noticeably

different in Bunny's solos and

in

some of the

other musical aspects of the arrangement.

Why

Brunswick

did this - these

multiple

takes,

issuing more than one take,

and making

a re-recording

in

which

they'd

record the

same

song

on

a

new master

and

issue it with the

same catalog

number

as

the

original -

is

just

impossible to decipher. There's just

no

logical

reason other

than that they really

didn't care

very

much.

There

usually isn't

any

technical

reason.

On the Marion Harris

record

I

was

referring

to,

she

does

a

rather

different

softer

version

of

the

titles

on one recording than the other,

but

you can't hear any technical fault on either

that

would

have

suggested

why

they

were re-recorded. It's just a total

mystery.

In

Canada,

only one take ever

seems to have

been

issued.

There

may

be

examples

where

more than one take was

issued

in

Canada,

but

my belief

remains that

they sent

up a metal

part and that was usually sufficient for all

the

Canadian

pressings

that

needed to

be

made.

The

market

in

Canada

was

just

so

limited

compared

to

the

American

market.

They

may

have

sent off different takes to

different countries because it saved them in

metal

parts.

If

they

had

a

mother

of

two

takes it

might

have

been just

as

simple to

send

one

to

Britain

for

the

British

pressings

and

keep

the

other

for

the

American, and not make off yet another metal

part

from the

American

mother

for the foreign

issues.

But it's

just

impossible

to

say. There doesn't

seem to be

any

rhyme or

reason to it.

There were also the foreign-language recordings

in

which

you'd

get

the

essentially

identical

recording

but

with

no

vocal

refrain.

These

were used

a lot

in

Germany,

but

an

unexplored

area

where there

were

a

great

number

issued

was

South America. They

appear

to

be

American

pressings

but

with

Spanish-language

labels.

It

may

not

even

have

been

for

South

America;

it

may

have

been

for

Mexico.

I

have at

least three

or

four

examples

in

a 40,000 series;

I

think

the

lowest

number

I

have is

in the 40,900s,

and the highest

in the 41,200s or

41,300s.

That

suggests that the series

continued for

some

time;

whether it started at 40,000 or

40,500 is hard to know. But these recordings

for

a non

English-speaking

market were regularly

made

by Brunswick.

We

know of

a

few

that

were

made

by

Columbia

for

Brazil

or

Argentina.

But

I think there

were far

more

U.S.

Brunswicks

made for those markets than

Columbias.

The

music

division

of

the

Brunswick-Balke-Collender

company

continued

in

operation

until

circa early

1930

when

Warner Brothers

Pictures purchased

the

music

division

from

Brunswick.

That

gave

them

a music-publishing interest as well

as the record division.

With

talking pictures,

Warner was interested

in

having

a

label that it could market its

stars on.

Jim

Kidd

has

a dealers'

catalog

which

is

a

gold-mine

of

information. It's

a

numerical

listing of all

Brunswick records

in stock,

I

think,

as

of

January

1931.

I

guess it

was

called the

1931 dealers' list but it really

only went

up to the end of

1930.

It lists in

numerical

order,

for

virtually

every

Brunswick

series

that

was

available,

the

records that were still

in the catalog,

and

also

noted

those

which

were

going to

be

deleted before the next annual catalog.

There

are

quite

a

substantial

number

marked

for

deletion,

mostly

pop tunes that

would

have

had a relatively limited vogue.

A lot of the

standard

numbers

went

right

back

to

The

acoustic

era and were

kept

in the catalog.

The

popular

items

always

had

a more limited

appeal

and would be deleted more quickly.

It

was

an

American

publication,

with

gaps

for

items

which

were

meant

to

be

territorial,

regional,

foreign-language, or

whatever.

Very

often

you'll

find

a

dotted

line

with

no entry

except

a

hand-written

word

such

as

"Spanish".

Jim

Kidd

has

verified that the

hand-writing

belongs

to

H.S.

Berliner,

the founder

and president of

Compo.

Many

of

these

hand-written entries

are

in

short-hand

or

in

such

an

illegible

hand that it's difficult

to

make

them out.

an

example

I

can think of is

Brunswick 4770.

I

don't

know

if

the

entry

has

"Canada"

printed

in it.

Sometimes

they have the

name

of the country that the number

was

assigned

to,

sometimes they don't. But the titles are

there,

and

I

can

make them out although I've

never seen the record. lt's "Hallelujah"

by

Harry

Richman,

coupled

with

"Sometimes

I'm

Happy"

by

Vaughn

de Leath.

Interestingly,

that was the

same as the English

coupling of

those titles

when

they

were

released

in

Britain, but by the time

Brunswick

4770

came

out

they

were

at

least

a

couple

of

years

old.

Maybe it

had

something

to

do

with

a

film version

of the musical

coming out

and

their

wanting to have something back

in the

catalog. But, interestingly, that number

was

never

issued

in the

U.S.A.

- it

was

Canada

only.

In

that

dealers'

list

there

were

some

numbers

or

entries

assigned

to

Canada.

There's

some

Scottish

ethnic

recordings

which

I

have

never

seen

but

which

are

entered

as

"Canada"

in the

book.

And

then

there

are

the

odd

jazz

recordings

which

appeared

issued

on those

Brunswick

numbers

only

in

Canada

coming

from

Vocalion

or

whatever,

or

in

a

couple

of

instances re-coupling

American

Brunswick

recordings onto

a different

number

for Canadian issue.

One

Jazz-related

item

-

Brunswick

4723,

the

famous recording of "Goin' Nuts" by the

Six

Jolly Jesters -

came

from American

Vocalion

15843

and was not issued on

Brunswick

in the

United States.

So there are

a

number

of

interesting

things

to

be

discovered

in

that

list,

which

was

clearly

used

in

Canada

and

must

have

been

acquired

by

Compo

when

it

took

over

Brunswick.

There

appear

to

be

inventory

numbers

written

in pencil

in the

left-hand

column,

which probably

indicate the stock of

records

that

were

still

extant

at

the

warehouse. For the most part the numbers are

very

small - it would be five, ten, three,

seven.

I

assume

that

Compo

was

able

to

acquire

that

stock,

limited

though

it

appears to have been.

The

dealers'

list

in

numerical

order

was

obviously

kept

up

during

the

year

because

after

the

last

number

entered

there

are

pasted-in entries

which

probably

came

from

supplements

which

continue

the

numerical

series

through

quite

some time

in

1931.

It

stops

suddenly

at the point that

Brunswick

went

under

and there were

obviously

no more

Brunswick releases or

supplements.

I believe

that

Brunswick

6128,

on

which

the

Boswell

Sisters are vocalists

with the Victor

Young

orchestra on "I

Found

A Million-Dollar Baby"

and

"Sing

A Little

Jingle",

is

one of the

items

that's

included

in

those

pasted-in

numerical entries.

I have seen a copy pressed

by the

Brunswick

company (not by Compo). the

highest number pressed

by Warner

Brunswick -

I

think

the

company

became

known

as

the

Brunswick

Radio

Corporation,

subsidiary

of

Warner Brothers

Records

with

a similar

name

in the

U.S.A. -

was

Brunswick

6214,

a

Cab Calloway recording.

The

Melotone

label

was

introduced

in Canada

at

approximately the

same time as it

was

in

the United States.

Brunswick's first budget

label

was

an extremely attractive silver and

blue,

although

the

Canadian

version of the

label

is

not quite

as

bright

and

shiny

as

the American.

But it

was

a quality product.

Given the

low numbers that I've seen in the

Melotone series

pressed

in

Canada,

I think

Melotone

started

in

Canada

just

about the

same

time

as it

did

in

the

U.S.A.

and

continued

along

with

the

Brunswick

label

until

Brunswick's

bankruptcy

in the

United

States. Calling it

"Brunswick's

bankruptcy"

is

a bit unfair. Warner Brothers allowed it

to

go

into

bankruptcy

because

they

just

weren't

making

any

money.

I

guess it

was

a

separate

corporate entity

as

part

of

the

Warner

Brothers

Pictures

empire

and

they

Just

let it

go

into

receivership.

At the

same

time

the

Canadian

company

followed

suit.

I

think

it

was

in

December

1931

that

Canadian

Brunswick

ceased

operation.

I'm

fairly

sure that it

went into receivership.

It wasn't

immediate

bankruptcy,

and it took

quite

a

number

of

years for the bankers to

get

rid

of

the

remaining

assets

of

the

company.

I

have

a friend

who

remembers,

at

the age of less than ten, visiting

Vancouver

with his

mother

from the Okanagan Valley

(I

think

he

lived

in Penticton at the time).

Outside

the

Hudson's

Bay

store

on

Georgia

Street at Granville there

were big trestle

tables

with piles

of

absolutely

brand-new

Brunswick records from

1931

which were being

sold

off

at

ten to

the

dollar.

Bob

was

allowed

to

spend

a

dollar

and

bought ten

records,

most of

which

he still

has

in his

collection.

So

I

think it

was just

in the

very early post World

War

Two years that the

assets

were finally being disposed of.

Alex

Robertson told the story

of

learning

that

there

were

Brunswick

materials -

I

think it

was mostly paper

material

(whether

it

included

things

like

ledgers

I

don't

know)

-

in

a

factory

building

in

Toronto

that

was

unused,

and

had

been

for

many

years,

and

apparently

was

a

Brunswick

warehouse.

In the United States

ARC never purchased the

Brunswick

interests.

They

leased

the

name

and the copyrights that

were

necessary

to

make

Brunswick records.

The factory that

was

used to

make

Brunswick

records or at least

the

principal

factory,

was

left

doing

odd

things

as

a

pressing

plant

-

radio

transcriptions,

and so on. It was eventually

acquired

by

Decca

in

1934

when the

Decca

label

was

established

in the

U.S.A.

If

you

look

carefully

at the

sequence

of

master

numbers

you can see that Decca picks up the

old

Brunswick

master series with

a

gap of

maybe

a

couple of

thousand

numbers,

which

probably

represents

transcriptions

and

other personal recordings that were pressed

at the old Brunswick plant

in that interval

of close to three years,

between

late

1931

and

1934.

I

think

the

Brunswick

master

numbers

were

in

the

36,000s

when

they

ceased operation

as

an

independent entity

in

1931,

and

Decca started

with

38,000s.

But it's

interesting

that

in

the

U.S.A.

Decca

acquired

the

Brunswick

facility

rather

than

build

a

new

one.

Of

course,

Decca being

a budget label it probably

made

sense

to

acquire

an existing

unused,

or

largely

unused, facility to

do its pressing.

When

Canadian

Brunswick

went

into

receivership,

there

was

no buyer to purchase

the facilities.

Compo

acquired

the

licence

rights to press and market the

Brunswick

and

Melotone

labels

in

Canada.

They

never used

the Brunswick facilities. they did acquire

a

few stampers

which they used -

you

can read

the

Brunswick-style

catalog

numbers

in the

wax.

But

very

soon it

became

an entirely

ARC-oriented product.

There

were

some

metal

parts

obviously

prepared for further pressings and they

were

used

by

Compo.

In the U.S.A.

you will

find

these

recordings

with

an

"E"

followed

by

five digits

and

a take.

I

don't

know that

there

are

many

that

show

the

ARC-style

matrix

number

in

Canada.

Compo

hand-wrote

the master

number

on its pressings as It did

for

all

of

its

other

products

with rare

exception.

I

can

recall

one

Isham

Jones

recording

which

has

the

Chicago

matrix

number

with

the

American-style

stamped

number,

rather

than

a

Compo-style

hand-written master

number. That would date from,

say,

1932.

So it wasn't

an

infallible rule

but it certainly

was the case that

most of

the

master

numbers

were

done

by

Compo.

I presume they just marked the metal part they

got

accordingly

to

keep

it

in

their

own

system.

I want to go back now to 1925 and the

acquisition of the Vocalion company by

Brunswick. There was a Canadian Vocalion company pressing

in Canada, and the records

are easily

distinguished

from the

American

counterpart.

The

Canadian

pressings

have

"Stamped

in

Canada"

on them

in the wax area

after

the

end

of the recording

before

the

label

starts.

The

American

Vocalion

was

a

red-wax

record

and

most

of

the

Canadian

Vocalions

have

black

wax.

The

typefaces

used

on

the printed

label

for the artist,

catalog

composer,

and title,

are

distinctively different to my eye. It's clear

that it's

a different

product

and that the

labels were,

in fact, printed

in

Canada.

The real point is that

Brunswick-Balke-Collender company

in

Chicago

acquired

the Vocalion company.

At that point,

for

one reason or another,

there

were

no

further

Canadian

Vocalions.

The

label

was

no

longer

pressed

in

Canada,

although it

may

have been imported in limited quantities.

I think that

was

in

early

1925.

It

could

be

that

Brunswick

didn't

think

there

was

a

sufficient

market to

have

another

label

in

Canada.

It's

hard to

know

why

they didn't

maintain

the

label

in Canada. It certainly

hadn't

been

in

existence

very

long

in

Canada,

at

most

maybe three or

four years.

It

was

one

of

the

labels

that

began

in

Canada

with

the

patent

situation

resolved

so that they could

do lateral-cut records.

I

think there

are

vertical-cut

Vocalions

at

the beginning.

Whether

any of the vertical

cuts were

done in

Canada

I can't say;

I don't

recall

ever

having

seen

one.

but

the

Canadian

Vocalion

Label

is

a

relatively

scarce

item.

They did

do

twelve-inch

pressings,

as did

Brunswick

in

Canada.

Despite

perhaps

evidence to the

contrary,

even

In

the

early thirties

Compo

had the

very

occasional

twelve-inch

pressing

of

a

popular catalog item.

The one that

I

know of

particularly

that

I've

actually

seen

and

handled is a twelve-inch

Guy Lombardo medley

of

songs

from

"The

Cat

and the Fiddle"

on

one side.

So that basically

is a very brief discussion

of

what

happened

to Vocalion

in

Canada

in

relation to Brunswick.

Again, it's

an area

that would be useful to research to find out

where its facilities were.

Curiously enough,

the

Vocalions that

I've

found

have

largely

been

in the

Ottawa

Valley,

but

I don't

know

if that had to

do with

where they

were

made

or

whether

there

was just

a

good

salesman

marketing

the

product

in that part of the

world.

That's all

I

have to say about Brunswick,

up

to the period

where

Compo

took

over.

The

Compo

story

is

one

of

very

considerable

complexity,

and

I don't really think

I'm the

one to tell that story. It is

Brunswick that

to

me is the most fascinating

subject.

(Our

thanks to

Jack Litchfield for transcribing Brian's taped memoirs

and submitting

them to us for unedited publication.)

|